This list initially ran on October 29, 2013. Also, read Bilge Ebiri’s essay on why Mulholland Drive is a great horror film.

One third of a century ago, Stanley Kubrick released The Shining and changed the face of modern horror. Except that he didn’t, at least not initially. The Shining was a critical dud and, at first, a financial disappointment. (Kubrick even got nominated for a Razzie for Worst Director.) But over the years, the movie has, to understate mightily, gained in stature. And its release seemed to us like a good cutoff point for our journey through the ensuing 33 years of horror cinema. After all, 1980 is an important turning point in the genre: The wild wild west of exploitation cinema (which gave us such titles as I Spit on Your Grave) had been largely tamed, the colorfully gruesome artistry of giallo (Suspiria, Deep Red) was on the wane, and Hammer Studios (home of Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed) had pretty much become extinct. Meanwhile, slasher movies were becoming slasher franchises, and the Age of Spielberg and the Age of Video were upon us.

And so, we’ve gone over the ensuing years and selected the best horror movies of this era. The parameters for the list are similar to the ones we used in our rundown of the 25 Best Action Movies Since Die Hard. The films included here are those we consider to be the best, not necessarily the most influential or seminal or representative. (There are, for example, lots of terrible and very popular slasher movies that did not make the cut.) And because there were two of us putting this together, we found the films we agreed on — mostly, with a few notable disagreements. Enjoy. And yell at us about what we missed in the comments section.

HONORABLE MENTION: Shaun of the Dead (2004)

Ebiri: We debated whether to include Edgar Wright’s zombie rom-com on our main list, and finally decided not to, for a variety of reasons. It’s not really horror, but it’s so in love with horror — and so in love with the possibilities of horror, with the sheer versatility of the genre — that it deserves a special place here. That said, if Wright ever does make Don’t!, the nonexistent movie advertised by the fake trailer he made for Grindhouse, we will happily make room on this list for him.

Edelstein: It’s a satire, but also the only post-Romero zombie film that uses Romero’s tropes to say something original— largely because it’s not a satire of zombie films but of English repression and juvenilia and suburban dullness. Edgar Wright and Simon Pegg give us a hero fighting for — and against — the world he knows.

25. Wolf Creek (2005)

Edelstein: I loathe Aussie Greg McLean’s film as much as anything I’ve ever seen, but as a piece of serial-killer torture porn it is unparalleled — it’s hauntingly, overwhelmingly cruel. The power is not just in what we see but what we imagine of the past and future of John Jarrat’s implacably sadistic evil twin of “Crocodile” Dundee, a creature at one with the emptiness and infinity of the Outback. My advice is sincere: Don’t see this. But omitting it from this (dis)honor roll would be untrue to the spirit of the genre.

Ebiri: It’s the most brutal of the “torture porn” movies, and probably the only one that isn’t boring, because its cruelty registers as more than just mere aesthetic doodling. And you’re right — it’s the only one that gets us in the imagination, where we’re most vulnerable.

24. Poltergeist (1982)

Ebiri: What happens when the early eighties Spielberg aesthetic — the playful, orchestral John Williams–ish score by Jerry Goldsmith, the lovingly hectic portrait of suburbia, the ennobled vision of childhood — meets the deranged vision of Texas Chain Saw Massacre auteur Tobe Hooper? Well, Poltergeist happens — an indelibly terrifying childhood memory for some, another step in the corporatization of horror for others. Of course, it could legitimately be both, and there’s a real tension here between director Hooper’s fondness for the disturbing and uncanny and producer Spielberg’s penchant for brass, for the operatic moment.

Edelstein: It’s a fascinating counterpoint to E.T., not surprisingly released the same summer: Here we see the dark side of Spielberg’s suburbia, where TV remote signals travel among houses that are too close together and in neighborhoods with no organic flow. The Indian graveyard thing is now a cliché, but it’s a good way of getting at how ahistorical suburban life is. (It’s always funny to see streets named for the natural resources of wildlife that were eliminated in order to build them.) Living in such a place, the film suggests, has the potential to tear families apart. I find much of the second half clunky, though.

Ebiri: Reportedly, the tensions were very real behind the camera as well, and rumors abound that Spielberg directed as much, if not more, of the film as Hooper did. And, of course, it’s been copied many times since — what isInsidious but basically just a more spiritual variation on this film’s main conceit?

23. The Stepfather (1987)

Edelstein: Terry O’Quinn is “Jerry Blake” in this sly, Hitchcockian slasher movie about a man (based on New Jersey dad John List) who longs so deeply for a perfect nuclear family that he’ll wipe the slate clean (i.e., massacre his wife and kids) when he reaches his (low) threshold for disorder. It’s a Reagan-era vision: The patriarch is folksy and mild in the time-honored TV tradition — and utterly estranged from the cruelty of his actions. It’s not the culture’s violence that drives people mad, the film implies, but its fake harmony — especially the sunny world of TV sitcoms, where every crisis is handily resolved (in 26 minutes), every family is a “bunch,” and every father knows best. Director Joseph Ruben and screenwriter Donald Westlake have drawn a clean line from Father Knows Best to Friday the 13th.

Ebiri: Every other scene with the family in this film is like a Folgers Coffee ad gone horribly wrong. It’s interesting how the darkly comic quality of films like The Stepfather (and a couple of other films on our list) eventually transmutated into the slick, “jokey,” wink-wink style of later horror. There was a pointedness to these films’ humor that’s been lost in translation.

22. The Descent (2005)

Ebiri: There’s something corruptingly blunt about The Descent. It starts off with the heroine’s family, including her young child, dying in a horrific accident. Then, it moves on to a story line that might as well have been cooked up in a sub-Cormanesque low-budget exploitation hothouse: Six young, beautiful women go spelunking into a dense cave system, get trapped by an earthquake, and are pursued by a pale, blind race of mutant cannibals who have bred and evolved underground all these years. It’s a graceless setup, but damn if it isn’t a terrifying one — a breathless roller-coaster ride of jump shocks through a world of pure, pitch black claustrophobia. The ruthlessness of the film’s opening scenes set us up for the fact that anything can happen, and strips us of any agency we might have as viewers. There’s no safe word here. It’s not torture porn; that genre turns on a very pointed conception of evil and soullessness. Rather, The Descent concocts a universe of base, raw impulse, and sets us loose in it.

Edelstein: I’d quarrel with the use of the word roller coaster, which suggests fluidity. What’s good about the film is how halting, lurching, and confused it often is (I don’t think I’m ever going to go exploring deep caves), and how suffused with grief over the loss of the protagonist’s little girl. I also like how subtly the director hints at — but never spells out — the relationship between the protagonist’s dead husband and Juno, the conniving Alpha Female of the pack. But I’m not as big a fan of this film as you are, perhaps because I find the performances iffy and the attacks too fractured and difficult to follow. Maybe they would have been better if the women weren’t quite so physically resourceful, so we could actually see them calculating in the face of an enemy far more accustomed to the terrain. It didn’t help that I saw the American theatrical cut, in which the original ending is simply hacked off. Beware of it: What’s there makes no sense.

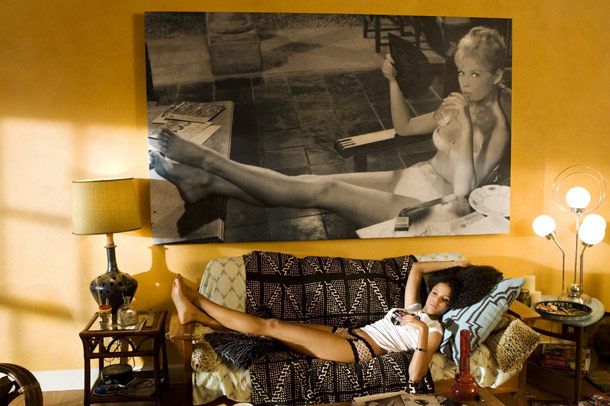

21. Death Proof (2007)

Ebiri: Quentin Tarantino’s feature-length contribution to the four-hour omnibus horror film Grindhouse (where it lived alongside Robert Rodriguez’s flaccid Planet Terror and Edgar Wright’s aforementionedfaux-trailer Don’t!) is, for all its movie references and its extended scenes of fetishized banter, somewhat uncharacteristic for the director. Tarantino usually loves to play with time and with the predictable: He tips his hand and distracts us, only to surprise us with something else that we didn’t see coming. In Death Proof, however, this takes on a more sadistic quality, which is perfect for the Z-grade schlock he’s referencing.

Edelstein: Tarantino is a sadist who reveres women and yet clearly gets off on their being physically abused. What makes him, I believe, an artist (albeit one to approach with extreme caution) is that he’s so out-front about his fetishes that (at his best) he allows us to scrutinize our culture’s misogyny without any sweetening. It’s the thing itself. Death Proof is, in that regard, his purest work. It’s a reductio ad absurdum. We watch two groups of very attractive females talk and talk and talk. We dig them in all kinds of ways. We also see them through the eyes of a deeply malignant presence (Kurt Russell), a man (once immersed in action cinema) who lives to stalk and murder women with his “death proof” car. Tarantino lingers obscenely over the carnage (and there’s the additional death of a hippie chick played by Rose McGowan that is even more horrible). Then he gives us another group of women (among them stunt woman Zoe Bell) who are man enough to kick the predator’s ass in the manner of Uma Thurman’s Bride in Kill Bill. As satisfying as the climax is (note how the man blubbers like a stereotypical “girl”), it hardly dispels the horror we’ve just experienced.

20. A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984)

Edelstein: Oddly, the first time I saw Wes Craven’s classic horror movie I was nowhere near as enthused about the grotty ghoul (Robert Englund) as by the terrifyingly brilliant conceit: that children couldn’t wake up from bad dreams, that they could literally kill you. Craven was drilling for fresh nerves. The monster — who emerged from amid the rusty pipes and shadows as if from the collective unconscious of high-school kids — could bend the rules of anatomy, growing larger and more lethal with every step. He would slice off his own fingers — imagine what he’d do to you.

Ebiri: I love how grimy and gritty this movie is, and was. I remember even the TV commercials looked cheap. I caught up with it later, on videotape, and the low-budget sleaziness, the roughness, only enhanced it for me.

Edelstein: Craven was still a primitive — he’d soon, with Scream, become slick — and the movie’s crudeness made it even scarier. I left the second Nightmare film midway and in disgust: Freddy had become a comedian and the killings were totally mechanical. But nothing could-and can — dispel the chill of Craven’s original.

Ebiri: I actually found Freddy’s wisecracking in some of the later films to be quite effective and disturbing – it should undercut the terror, but somehow, in this case, at least for a while, it enhanced it: That he could be so cavalier about killing us (unlike the tormented Michael Myers or the perfectly opaque Jason Voorhees) meant that we were nothing to him. But eventually, he did become a bit of a joke.

19. Masters of Horror: Homecoming (2005)

Edelstein: In 2005, one of the few peeps in pop culture that the occupation of Iraq had turned unspeakably vile was an episode of Showtime’s Masters of Horror series directed by Joe Dante from a script by Sam Hamm. The Bush-Cheney administration made it a felony to photograph the coffins of soldiers, supposedly to protect the feelings of the families doncha know… In Homecoming, the dead soldiers rise from those coffins to cast votes against the administration that sent them off to war under false — criminally false — pretenses. The film is cartoonish — one of the protagonists is a right-wing harridan modeled on Ann Coulter — but also angry and passionate. It proved that horror doesn’t need to dwell in the shadows (or grindhouses). It can be incendiary.

Ebiri: I love the queasy feeling I get in this film’s opening scene, when these vet-zombies emerge from a truck to attack the protagonists (who actually turn out to be the bad guys). We see the soldiers only in silhouette, and they’re carrying canes and crutches. They stagger like zombies — or is it that they stagger like wounded soldiers? The film keeps it ambiguous for a moment — just long enough for us to realize that, in a country where the war wounded and the war dead are kept hidden away and out of sight, like a monster in the closet, there’s little difference. It’s an intensely disturbing movie, and even though we’re cheating just a little bit by including a made-for-cable film in here, it totally belongs.

Edelstein: Dante said it best in the Village Voice: “This pitiful zombie movie, this fucking B movie, is the only thing anybody’s done about this issue that’s killed 2,000 Americans and untold numbers of Iraqis? It’s fucking sick.”

18. Ravenous (1999)

Edelstein: Director Antonia Bird replaced the original director of this frontier cannibal saga two weeks into shooting, and it’s admittedly a bifurcated effort — underrated on release (it flopped), even by me. The first, more suggestive half is tantalizingly scary. A captain (Guy Pearce) is decorated for heroism in the Spanish-American War and then exiled to an isolated fort high in the Sierra Nevadas — a godforsaken place where in winter the only passers-by are starving wagon-trainers. Why exile a hero? It seems he initially played dead in the heat of a battle, then awoke to find himself lodged under a messy corpse, the blood from which ran his mouth — invigorating him à la Popeye the Sailor Man. They gave him a medal but wanted nothing more to do with him. Bird creates a world of blinding white peaks and deep black crevices in which demons might lodge, a world of humans driven batty from fear and isolation, where reaching out to other people sometimes takes the form of ingesting them. Maybe the metaphor would be better if left suggestive, if the strange new appetites were somehow the product of anxieties associated with American westward expansionism and “Manifest Destiny.” But the second, more melodramatic half has its high spots, chiefly the glittering-eyed Robert Carlyle, who looks like just the sort of fellow who’d think it his duty to explore things that the rest of us, deep down, want to know about but wouldn’t dream of investigating ourselves. “Er, Robert, tell me … does it really taste like pork?”

Ebiri: I love how epic, how lush this film is, and yet at the same time so tough, and so funny. Bird, who just passed away this weekend at the untimely age of 54, seemed to really be coming into her own with this, and it seems that its failure really affected her ability to get projects off the ground. She went on to work regularly in TV, but this appears to have been her last theatrical feature.

17. Se7en (1995)

Ebiri: A sick, sick, beautiful movie, David Fincher’s grisly, grimy serial killer drama is all horror subtext made dramatic text. Somebody is killing people according to the Seven Deadly Sins. It’s the job of two archetypal (some might say clichéd) cops to stop him: A soon-to-be-retired Morgan Freeman, a worldly veteran who’s had it with this broken world, and rookie hothead Brad Pitt, whose blithe indifference is about to be put to the test. In fact, ignore the too-obvious-by-half script and focus on the way Fincher makes this fallen world so gruesomely tactile. Is the movie a bit too in love with the serial killer’s unspeakable, yet still somehow “neato,” methods? Perhaps, but it’s horrified by its own fascination, and so are we. This is one of those movies you’ll want to take multiple showers after, to little avail: The stain of this world will not out.

Edelstein: I couldn’t agree more that the dialogue is wooden. But this is an invasively ghastly film — as perfect in its way as any on this list. (I hate it.) The killer’s staged murder scenes have a clammy beauty — by far the most loving images in the film. Beyond that, there’s a shootout that comes at the detectives’ first sight of the murderer that’s perhaps the scariest of its kind I’ve ever seen. He’s distant, not quite in focus, but the shots come at us from angles I could never imagine. SPOILER: At the time I was quite upset at the fate of Gwyneth Paltrow. Now that she’s become so insufferably Goopy, it’s possible I’d enjoy the ending more.

Ebiri: I have a good friend who thinks that every movie should end with Gwyneth Paltrow’s head in a box.

16. Ringu (1998)

Edelstein: Hideo Nakata’s irrationally terrifying ghost movie never had a proper release in the U.S. — it bubbled up from the ground and soon everyone was talking about it. No wonder. This is the perfect fusion of ancient horror — the wraith who claws her way out of the ground, her face hidden by a curtain of black hair, driven only by rage — and modern technology, with its own dark recesses. It’s the vagueness of her shape that chills you to the bone. The American remake (starring Naomi Watts) was surprisingly not bad, but it wasn’t grounded in our legends; it was no more than a decent shocker.

Ebiri: A number of the films on our list are, to varying degrees, cautionary tales about the all-consuming nature of modern, and particularly video, technology. And while some of those films are masterpieces, their warnings are easy to ignore, because we know and understand the world of video and media so well, as modern consumers. But one thing that’s so great about Ringu is that it takes that idea and makes it so other, so unfamiliar and troubling.

15. The Blair Witch Project (1999)

Ebiri: So many years after all that hype, and the attendant backlash (not to mention the pathetic attempts to turn it into a franchise), how does The Blair Witch Project fare? Still pretty goddamn terrifying, thank you very much. The setup may be simple — three kids go out into the Maryland woods to make a documentary about a local myth — but it works.

Edelstein: The backlash was nearly as intense as the first response, but this remains the standard for limited-perspective horror. It’s not great art, but it’s proof that vague shapes and crackling twigs can be scarier than million-dollar FX — that nothing is scarier than nothing.

Ebiri: I also like the tension between the three leads: For me, their mounting anger at each other and fear of their surroundings really drives the film’s scares, putting the lie to the misguided notion that it’s all gimmick. That said, the gimmick is pretty great, even though it’s also kind of a ripoff of an earlier, inferior film called The Last Broadcast.

14. Day of the Dead (1985)

Edelstein: Count me among those who were hugely disappointed at the time of the movie’s release. George Romero’s third Dead film had been a long time in coming, and it was public knowledge that his original, allegedly epic script had been eviscerated by budget cuts. But the movie has worn well: Today it seems far more interesting than the crowd-pleasing splatterfest Dawn of the Dead. The limited scale intensifies the feeling of helplessness, and Romero introduces themes with which we still grapple: How do societies reorganize themselves in the face of chaos? Can the threat be absorbed, even domesticated? How much power will be seized by the military-industrial complex? Our culture has now domesticated zombie cannibals: They’re everywhere. But the horror here was still primal.

Ebiri: I love how Romero keeps coming back to the “living dead” concept, not to milk it for more money (as many other filmmakers who return to their original “franchises” do), but to keep exploring all the various ramifications of this type of apocalypse. Even when the films aren’t all that good, the ideas remain interesting and very much alive. Later directors who work in this genre owe so much to him — including Danny Boyle, with 28 Days Later. I’m also constantly wowed, particularly in this film and a couple of others (including the fantastic 1998 movie Monkey Shines) of what a deft, clean narrative director he is. It’s a talent under-appreciated in modern horror cinema, where the shock is so much more important than the story. Romero is the rare director who can do both so, so well.

13. Cure (1997)

Ebiri: Kiyoshi Kurosawa is too idiosyncratic an artist to label him a “J-horror” filmmaker (though he did make one of the more representative examples of the genre with Pulse, which is good but didn’t make our list). And this tense, otherworldly masterpiece is as much a Lynchian nightmare as it is a cerebral slasher flick. A man is wandering around Japan compelling ordinary people to become murderers – not in a threatening, Jigsaw-from-Saw way, but in a mesmeric, cajoling way, by essentially hypnotizing them with the minuscule details of life. Meanwhile, the investigator trying to unravel his crimes is having his own hellish experience with the mundane and with domesticity. This is the kind of movie where the ominous throb of an empty washing machine can be as terrifying as the sight of a man brutally killing somebody.

Edelstein: The idea of “psychic enabler” forcing hitherto obedient people to act on their deepest, most buried impulses was particularly beloved in Japan, where the Cinema of the Repressed is, well, Japanese cinema. The last couple of shots are head-scratchers (I had to have them explained to me), but the film transcends its murkiness and eats into the mind. Cure is what ails you.

12. Ginger Snaps (2000)

Edelstein: The ne plus ultra of Emo-Girl horror, John Fawcett’s marvelously assured 2000 Canadian movie (from a script by Karen Walton) gets the balance of humor and shocks just right. Katharine Isabelle is the red-haired 15-year-old who’s having her first (delayed) period—which happens to coincide with an attack by an evident werewolf that has been systematically disemboweling the suburban neighborhood dogs. Emily Perkins is her dark, glum (slightly) younger sister who has pledged to follow her to the grave or beyond. No film — straight or genre — has ever captured sisters’ mixture of dependence and rivalry. Mimi Rogers is the rare caricature of a mom that stings. (She hates her husband and blames herself for everything her girls are going through.) There’s no facetiousness or camp in the killings, which are graphic and upsetting. Because psychosexual traumas do have consequences, sometimes deadly.

Ebiri: Exactly. The central relationship between the sisters in this film is so involving, even tender, that it’s hard to step back and get any kicks from the genre elements in this film. It’s really a tragedy, and when I first saw it, years ago, the final shot absolutely wiped the floor with me.

11. The Host (2006)

Edelstein: If there’s one thing to be gleaned from Bong Joon-ho’s sensational Korean film The Host, it’s that our cinema’s most celebrated auteurs need to make more marauding-giant-monster movies. The genre is so fabulously elastic! The Host packs a lot into its two tumultuous hours: lyrically disgusting special effects, hair-raising chases, outlandish political (and anti-American) satire, and best of all, a dysfunctional-family psychodrama — an odyssey that’s like a grisly reworking of Little Miss Sunshine.

Ebiri: Bong is a uniquely agile filmmaker, though. He’s proven over and over again — with this, with Mother, with Memories of Murder — his ability to mix all these disparate elements into something that’s fluid and compelling and has real emotional through-lines. Some years ago, when I interviewed him for Vulture, I asked him about this, and he gave me a response which I think makes sense, though I’m not sure: “I love genre movies, but I hate genre conventions.”

Edelstein: In the end, though, this is a real horror movie. It’s hard to shake off the first sight of the creature in the far distance, hanging from the side of a bridge like some kind of pupa, then dropping into the water and gliding toward shore (to the oohs and ahhhs of the dopes on the bank, who throw food to it). This is a portrait of a country’s deepest anxieties, which just happen to be distilled into a mandibled squidlike reptile. It has the tang of social realism.

10. Videodrome (1983)

Edelstein: Here’s a cool story: I was called at random when I was living in Boston in 1982 to go to a very early preview screening of what turned out to be Videodrome. I went with my college pal Paul Attanasio, now an accomplished screenwriter. It was a legendary disaster. The walkouts began early and continued throughout. After we’d filled out our cards, a testing guy came out and asked if anyone wanted to come and talk about the film. We joined about 15 people at a long table. Cronenberg was there but didn’t identify himself until the end. We were asked for our reactions and one by one they came. “It was terrible. What was it even about?” “One of the worst movies I’ve ever seen.” On and on. Then I said, “Uh… I think it’s a masterpiece.” Paul chimed in with his enthusiasm. I did say there were parts were hard to follow. The film took a year to be released. Some of the scenes were shortened and there were lines looped in to clarify the plot. But it was the same movie. Cronenberg later told me that in the midst of the fights with the studio he’d say, “Yeah, but what about those two guys?” So once in my life I did have a positive effect. Needless to say, the film flopped in theaters but found its audience on — what else? — video.

Ebiri: It’s quite possibly the gnarliest movie on this list, part dystopian video age manifesto, part nightmarish gross-out mindfuck. I mean, just look at the set-up: James Woods intercepts a pirated video signal that presents terrifying visions of torture and violence, is sucked into it, and begins to sprout new bodily orifices, while his belly turns into a tape deck.

Edelstein: My favorite Cronenberg film is The Brood, but Videodrome—however crude in places — is his most visionary. It takes his obsession with “body horror” — with the manifestation of thoughts and emotions on the human anatomy — to a futuristic new level. We’re lured in and then ensnared by porn — by our own voyeuristic appetites. Then the transformation begins. The movie owes something to J.G. Ballard’s psychosexual visions of man fusing with machine, but it’s more successful at capturing that idea than Cronenberg’s adaptation of Crash.

Ebiri: The film supposedly presents the gradual decaying of his reality, but sometimes I wonder if it isn’t all a hallucination from the get-go. Watch the ease with which he seduces the beautiful Debbie Harry on a TV talk show; Cronenberg’s vision of the video revolution is really that of a wish fulfillment fantasy gone berserk. The more we want to enter the dreamlife of the video image, the more it wants to enter us. The fact that the film has since dated somewhat, with all those awful analog TV signals and rows and rows of videotapes, now just adds to the discomfiting otherworldliness.

9. Evil Dead 2 (1987)

Edelstein: Extreme gore and slapstick, never more gleefully orchestrated than by former Boy Scout and Three Stooges fan Sam Raimi. It doesn’t have the nasty kick of Raimi’s breakthrough original, but the set-pieces are stupendous, especially a fight between Bruce Campbell and his demon-possessed hand that ends (more or less) with the help of a chainsaw. Raimi’s vision is pantheistic and all of a piece: Nature is invested with evil, with every limb (plant or animal) apt to develop an evil mind of its own.

Ebiri: It seems so weird nowadays to think of Sam Raimi as the guy who did the Spider-Man and Oz movies (as great as his first two Spider-Manmovies are.) He used to be the can-do, pull-out-all-the-stops, schlock masterpiece guy, and the opposite of slick. But watching the Evil Deadmovies again, I was struck by what cartoons they are, particularly this second one. Maybe it’s not so much that Raimi got subsumed by mainstream culture, but more that mainstream culture caught up to him.

8. John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982)

Ebiri: It’s a paradox of the horror genre that it promises to show us things we’ve never seen before, things that will presumably blow our minds, and yet so often has to rely on good old-fashioned scares to make an impact. (Even a mindbending masterpiece like Alien is, essentially, a haunted house story set in space.) John Carpenter, noted disciple of H.P. Lovecraft, the original indescribable horror guy, managed to pull off the impossible with this, an ostensible remake of Howard Hawks and Christian Nyby’s 1951 sci-fi classic. The film approaches the realm of the experimental with its creature effects. Observe: In what might be the film’s most shocking scene, a man’s stomach cracks open and becomes a giant, monstrous jaw, before vomiting forth green goo, while his actual head detaches itself, slithers along the floor pulling itself by a reptilian tongue, before sprouting giant spider legs and attempting to scurry away.

Edelstein: Rob Bottin, where are you? Yes, I love Rick Baker’s work in An American Werewolf in London and other films, but Bottin’s work with “bladders” in The Howling and the transformations in The Thingare sublime (meaning beauty plus horror). Carpenter’s The Thing was widely panned on its release: How dare he go up against Hawks (one of his models). But this is a far different animal — a study in the unknowability of our fellow men — and despite some crude dialogue it casts a spell.

Ebiri: For me, those effects, the unfamiliarity of the characters, and that desolate Arctic setting all add to a weird sense of helplessness, as if the movie has placed me in a terrifying and unfamiliar place and pretty much left me there. It’s the horror movie equivalent of a complete mental breakdown.

7. Re-Animator (1985)

Edelstein: Stuart Gordon’s gleefully gory mad scientist romp is head and spurting trunk above the rest. Loosely based on stories by H.G. Lovecraft, the movie shows off Gordon’s talent (honed at Chicago’s Organic Theater) for mixing Gothic, Grand Guignol and farce into a potent witch’s brew. Every scene has a comic charge—and with a payoff that’s always more splattery than you expect. Jeffrey Combs is the clammy Herbert West, a prisspot never happier than when pushing his giant syringe (filled with chartreuse fluid) into the veins of something dead and then standing back to the count the seconds until reanimation. Bruce Abbott is his peerless straight man, Barbara Crampton the lovely med school dean’s daughter who winds up naked and strapped to the table while West’s decapitated rival megalomaniac (David Gale) executes a perfect visual pun with his severed head. Incomparable!

Ebiri: The “comic charge” you mention is key. What I particularly love about Re-Animator is how it’s all pitched at such a melodramatic level — the performances, the gore, as well as the ideas. Combs’s performance starts off big in the opening scene, where he’s discovered flailing around on the floor (with his old mentor, whom he’s tried to “re-animate”), and gets even bigger as the story proceeds. And yet, even though it’s a very funny movie, it never veers into camp. That’s an extremely difficult line to walk, and Gordon seems to do it effortlessly.

6. Blue Velvet (1986)

Ebiri: Was this the first indication we got from David Lynch that all was not well in his conception of small-town America? Up until this point he’d made the industrial sci-fi art film Eraserhead, the Victorian period piece Elephant Man, and the misbegotten Dune. Now, right from its opening shots showing how life in an idyllic world of manicured lawns and white picket fences can suddenly go surreal and rotten, this director gave us for the first time, in full bloom, the vision of a world that would quickly come to be known as “Lynchian.” And it’s a genuinely terrifying one: A world of severed ears, freakish disguises (and, of course, subsumed identities), bogeymen who dance to Roy Orbison in the night. So much horror has its roots in the fairy tale. I think this is probably the film on our list most likely to become an actual fairy tale a hundred, two-hundred years from now — if it hasn’t already.

Edelstein: I was a critic in the mid-eighties, one of the low points in American cinema, and this fetid little movie was positively life-affirming. Blue Velvet is camp, but breathtakingly surreal camp, with a vicious sting. It’s a Hardy Boy’s mystery that would put the Hardy Boys in Bellevue. Lynch gives us a polite, gee-whiz young hero — he resembled Lynch himself back then — who is introduced via an abused woman (Isabella Rossellini) and her monstrous abuser (Dennis Hopper) to his own vilest impulses. The deceptive surface of suburbia is once again at the forefront: Amid the blades of the green grass is a rotting human appendage. The bluebird of happiness is apt to feed on flesh. Angelo Badalamenti’s ravishing score captures — like Blue Velvet— all the loveliness and inexplicable horror of this world beneath the world. A ghoulish Dean Stockwell materializes in the kind of scene that Lynch puts in every one of his movies and calls, “the eye of the duck” — the apogee of weirdness. Along, of course, with this: “Heineken? Fuck that shit. Pabst. Blue. Ribbon.”

5. Donnie Darko (2001)

Ebiri: Does Richard Kelly’s stunning cult debut even count as a horror movie? Yes, especially if you ignore the literal-minded, sci-fi director’s cut (which is disastrous, and ruins much of the movie’s elegant narrative). In its theatrical version, Donnie is one of the great films about that great horror movie subject: Coming-of-age in suburbia, a world where violence and evil seem to lurk around every corner. In one of the film’s most beautiful scenes, Donnie goes to a movie theater to watch The Evil Dead. Look at the marquee, though, at what else is playing: The Last Temptation of Christ. As much as it’s a horror movie, Donnie Darko is also something of a modern Christ tale — a story about a young man who redeems the horrid world he lives in and, in so doing, finds real beauty in it.

Edelstein: I’ve often thought of The Last Temptation of Christ as It’s a Wonderful Crucifixion, meaning Jesus gets to live out the ordinary life he’d have lived if he hadn’t accepted his mantle — and then decides to sacrifice himself, whatever the pain, for the greater good. That’s Donnie Darko. Donnie’s existence (when he was supposed to die) opens up deep fissures in his world, but the great thing about the original theatrical cut is that he might actually be a vaguely schizoid teen in the early stages of breaking from reality. I agree: The director’s cut spells out things that are far better left ambiguous. In fact, seeing those added scenes kind of spoiled the film for me in retrospect. In any case, no work has ever illustrated one of the greatest of all adolescent self-pitying lyrics (via Gary Jules’s cover of Tears for Fears’ “Mad World”): “I think it’s kinda funny/I think it’s kinda sad/The dreams in which I’m dying are the best I’ve ever had.”

4. The Fly (1986)

Ebiri: This might be Cronenberg’s masterpiece for me. It starts right in the middle of a conversation between charming, oddball inventor Jeff Goldblum and beautiful, intrepid journalist Geena Davis, and it never quite leaves that register: What was billed as a hi-tech remake of a 1950s creature feature becomes, in this director’s exacting hands, a chamber drama about desire, consumption, science, disgust, sex, and death. It’s beautifully spare and internalized, as if the film is taking place inside someone’s head — understandable for a film that is partly about trying to get the scientific and mechanical mind to grasp the unpredictable beauty (and horror) of flesh. (“I haven’t taught the computer yet to be made crazy by the flesh … the poetry of the steak.”)

Edelstein: Reconceiving the original short story to show the scientist transforming from within was genius, and it allowed us to see Goldblum’s Seth Brundle (best name ever?) exulting in his superhuman powers before the changes turn anti-human. Remember how his eyes shine from within the muck while he speaks of being “the first insect politician” — the one to forge a bond between humans and the relentless killing machines of the world of the flies?

Ebiri: And it’s one of the most moving horror films you’ll ever see. That element does come to some extent from the classic 50s B movie ethos; so many of those flicks were about the tragic transformations of good, ambitious men into pathetic, horrid monsters. As always with Cronenberg in this era, the gruesome special effects are gory, effective, and poignant — they underline the fragility of our base, human physical reality.

Edelstein: Cronenberg reportedly conceived of the film while watching his father die — and wondering in his Cronenbergian way whether the man was decaying or turning into something else. (All hail the new flesh.) This is as close as he has come to a real romance: His girlfriend loves him enough that she doesn’t turn away.

3. Audition (1999)

Ebiri: In a way, it’s not fair to even put this film on here, because it’s best to go into Audition without knowing anything about it. It starts off gently, forlornly, with a man losing his wife to a terrible illness and his young son standing at the door of the hospital room, both of them thunderstruck. It’s not an entirely unheard-of way to start a horror movie — so many entries in the genre turn on stories of loss — but for a while, director Takashi Miike lulls us into thinking that we’re watching a drama, perhaps even a mild romantic comedy. Ready for romance again years later, and egged on by a movie producer friend, our hero stages fake auditions for a movie, in an effort to find the right woman … and he finds the absolute wrongest woman there is. But the fact that the movie goes for so long in that weirdly gentle, vaguely romantic register is both a brilliant stylistic gambit and a harrowingly effective thematic device, because the movie is all about turning romantic clichés on their heads. It’s a cosmic, vengeful joke on male entitlement, and the fact that our avenging angel turns out to be so disturbed, so broken, so deeply fucked up is both profoundly disturbing and, well, kind of funny.

Edelstein: My wife has never forgiven me for showing this to her, although I think (as you say) that the idea of a woman punishing a man for exploiting her resonates with most women. Maybe it’s that the vengeance is so excruciating, and that it comes from a perfect Japanese ingénue — willowy, smooth-skinned, elaborately polite.

Ebiri: It’s a film of amazing contrasts, full of nods to both the usual nonsense men tell each other, like “There are plenty of fish in the sea” as well as variations on the concept of Ms. Right. And then, once the movie turns, the transformation is profound on every level. What had been a methodical, somber narrative becomes an expressionistic freak-out, with enough reality-altering symbolism and dream visions and disturbing sexual violence to make Ken Russell blush.

Edelstein: During the ghastly climax, I had fun closing one eye and with the other watching various ashen older men stumble toward the exit.

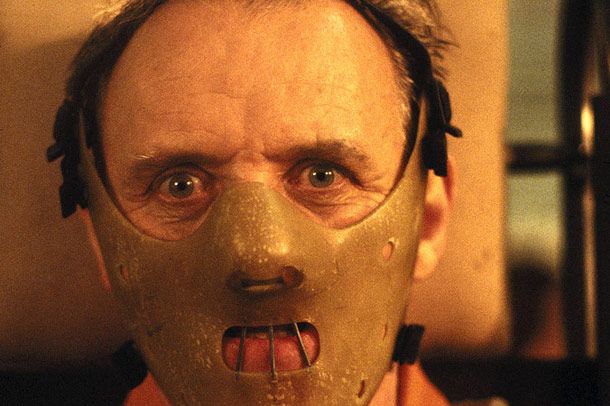

2. The Silence of the Lambs (1991)

Edelstein: Thomas Harris’s Silence of the Lambs is the gold standard of serial-killer novels and cemented the forensic fetish in pop culture, but director Jonathan Demme brought something different to the movie. This is one of the few horror films made by a card-carrying humanist — a filmmaker for whom the killing of every character is like a death in the family. It’s not the Hannibal Lecter story, it’s not Grand Guignol: Demme’s sympathies are firmly with the young female FBI agent (Jodie Foster, carrying the baggage of Taxi Driver and John Hinckley) who struggles to overcome demons both personal and societal. The rub is that she does it with a mentor, Lecter (Anthony Hopkins), who is himself the embodiment of everything she fears — who strengthens her and feeds off her at the same time.

Ebiri: We all know that Best Picture Oscar wins are never any gauge of real quality, but still, the fact that this is one of the few modern horror films to even be a contender (and it’s the only one that’s ever won) suggests that the Academy, along with the culture at large, picked up on the humanism that you mention. (And it’s a humanism that, sadly, none of the subsequent sequels even bothered to display. I’m sure it will also be sorely lacking from the inevitable “reboot,” whenever it happens.) When I first saw this movie, I thought it was one of the greatest films I’d ever seen, and I immediately declared I never wanted to see it ever again.

1. Mullholland Dr. (2001)

Edelstein: Yes, it fits into the horror genre, as almost all the films of David Lynch do: Few directors are as deft at putting their unconscious onscreen in all its temporal fractures, sudden dissonances, and even more sudden harmonies. This is a primo psycho-noir, in which Lynch regards the long palms, Hollywood hills, and movie-star cars and sunglasses ironically, in quotation marks — except the dreamer of the dream is never smiling, so you’re never sure when (if ever) to laugh. The movie flirts with being a conventional whodunit. Then — this is what makes it horror — the story line splinters, doubles back on itself, and begins to forge an entirely new set of connections. Roles change. Identities mutate. Things that made no sense make less sense — then, suddenly, more sense.

Ebiri: That fracturing also allows Lynch to play even more with the horror element in this film. There is one particular moment, involving someone — or, more accurately, something — lurking behind a dumpster in the back of a diner. It’s one of the great “shocks” in horror cinema. But the beauty of it is that Lynch can let this unnerving scene just hang there — he doesn’t have to then go and pay it off with the typical explanations, or a whole story line. It lurks in the corner of your subconscious, like a bad dream you once had.

Edelstein: There are pieces here that will never fit, except maybe in Lynch’s dreams. And yet this distinctly Hollywood nightmare makes a deeper kind of sense. Here are the romantic longings at the heart of so many movies — side by side with the id that powers the industry.

Ebiri: Even more amazingly, Lynch originally shot this as the pilot for a TV series for ABC. Then, when the show didn’t get picked up, he decided to turn it into a feature film and changed the ending. First of all, how incredible that this gambit worked! And secondly, what a perfect real-world correlative to the story’s dark Tinseltown stirrings. Many modern filmmakers have tried to capture the unreal darkness at the heart of the industry and failed — Brian De Palma’s Black Dahliacomes to mind. But Lynch, the perpetual outsider and naïf, nails it in a way no insider ever could, by embracing the unnerving (dare I say, Lynchian?) paradox of the words “Dream Factory.”