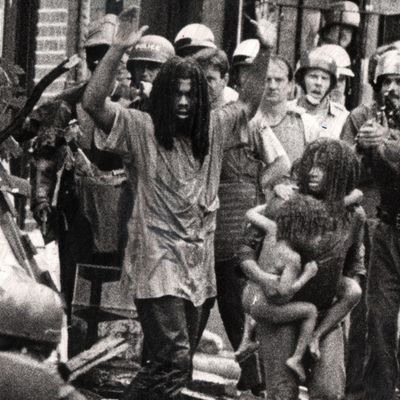

Jason OsderÔÇÖs electrifying nonfiction film Let the Fire Burn examines the events of May 13, 1985, when the leaders of the city of Philadelphia decided in their wisdom to drop a bomb on the roof of the headquarters of the African-American ÔÇ£anarcho-primitivistÔÇØ group MOVE, a conflagration that ended up killing eleven people (including five children). It also wiped out 60 homes.*

The key to the filmÔÇÖs power is OsderÔÇÖs decision not to tell the catastrophic story via present-day talking heads looking back. He goes to the video archives. The spine of LTFB is footage of a commission held several months after the tragedy, in which the surviving principals were questioned, politely but penetratingly. ItÔÇÖs hard to believe, in fact, how thoughtful and alert and un-sensationalistic these commission members are in the face of lies and/or abuse from all sides: They put the present-day U.S. Congress to shame. In some ways, Let the Fire Burn can be seen as a brilliantly condensed and illustrated version of those hearings. And by sticking with historical footage ÔÇö much of it in the form of live news reports as events were unfolding ÔÇö Osder has made a historical documentary thatÔÇÖs astonishingly in the present tense.

Thirty thousand rounds of ammunition were fired by police on a group that had four weapons, none of them ÔÇö despite police claims ÔÇö automatic. But this is not a whitewash, so to speak, of MOVE, the mission of which was borderline incoherent and the leader ÔÇö who called himself John Africa ÔÇö unbalanced. He oversaw the starvation and probable abuse in other ways of those children. He was in the business of provocation: He wanted the war that came. Perhaps he even knew that the apparently racist police department would be gunning for revenge (literally) for the death of an officer during a raid on the group seven years earlier.

But the movieÔÇÖs most repellent figure is the police commissioner, Gregore Sambor, who seems at once contrite and smug, and who appears to have let the fire burn even when the order to put it out came down ÔÇö finally ÔÇö from Mayor Wilson Goode. It took a long time for Goode to give that order: He claimed he thought he saw water being sprayed on the fire on TV, but that it tuned out to be bad TV reception. IÔÇÖm going to repeat that sentence: He claimed he thought he saw water being sprayed on the fire on TV, but that it turned out to be bad TV reception. Thirty square blocks. Thirty square blocks.

Two police officers involved in the 1978 fracas are seen going around the house to the back alley, out of sight of the cameras, where a group of MOVE members (including the children) attempted to surrender. For some reason, they came out and then went back into the fire. Why, asks a Reverend on the commission, would anyone run back into a raging fire? It makes no sense unless 

You donÔÇÖt see what happened. But you know. One of the few cops to distinguish himself that day ÔÇö a man who ignored orders not to rescue a burned child called ÔÇ£BirdieÔÇØ ÔÇö later found the words, ÔÇ£NÔÇöÔÇô LoverÔÇØ on his locker. He was ostracized, left the force, and had a breakdown. No one from the city was ever prosecuted.

Let the Fire Burn is a time machine and a triumph of documentary form. Osder shows that there are truths out there waiting to be found ÔÇö that footage already shot can make history in all its terrible finality breathe.

* This review previously stated that the Philadelphia police department had destroyed 30 square city blocks. That was incorrect. We regret the error.