The first thing to know about Dear Mr. Watterson, Joel Allen SchroederÔÇÖs documentary about Calvin & Hobbes creator Bill Watterson, is that itÔÇÖs not really a movie about Bill Watterson. No, itÔÇÖs a movie about Calvin & Hobbes. That may sound like a pointlessly subtle distinction, but itÔÇÖs an important one. Watterson notoriously shuns the spotlight: He wasnÔÇÖt a very public person when he was writing and drawing Calvin from 1985 to 1995, and, now that itÔÇÖs over, heÔÇÖs even less so.

This poses something of a problem for Schroeder, a longtime devotee of the comic strip about a young dreamer and his imaginary (or maybe real, but just unseen by others) tiger. He doesnÔÇÖt want to go down the road of recluse-spotting, trying to dig into WattersonÔÇÖs private life┬áÔÇö sort of a variation on what Shane Salerno did (awkwardly) in Salinger. Instead, being the loyal, respectful fan that he is, Schroeder wants to try to find the artist in the work ÔÇö to explore Calvin & HobbesÔÇÖs place in American pop culture and see what that says about Watterson himself. Which is interesting. Except that he doesnÔÇÖt really do it.

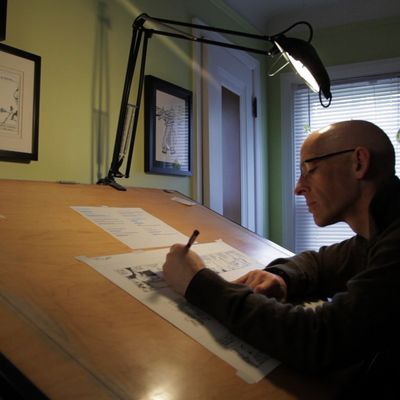

Schroeder opens on his own experiences with WattersonÔÇÖs work. He goes digging for the first Calvin book he owned, and even interviews his parents about the strip. But although the director serves as something of a tour guide throughout, most of the film feels like a slick, informational, talking-heads journey. Schroeder gives us montages of ordinary people talking about how the strip spoke to them in different ways. He brings out other artists for whom it was a revelation. He trots out historians. He goes into some of the earlier influences on the strip, including Winsor McCayÔÇÖs Little Nemo and Walt KellyÔÇÖs Pogo. He does delve ÔÇö briefly, but fascinatingly ÔÇö into how WattersonÔÇÖs hometown of Chagrin Falls and the surrounding area found its echo in the landscape Calvin and Hobbes wandered and frolicked through.

But you want the film to stop and tell us more┬áÔÇö to go somewhere interesting and maybe stay there for a bit. As someone who found the comic strip interesting and entertaining but decidedly un-life-changing, I was waiting for some kind of revelation, some moment of insight that might open the doors of perception for me. For example, Calvin and Hobbes were apparently named after the religious leader John Calvin and the political philosopher Thomas Hobbes; to what extent did Watterson toy with these historical echoes in the strip itself? People keep talking about how ÔÇ£philosophicalÔÇØ the strip is, but nobody actually explains how. Or, more accurate, nobody gets to explain how, because the movie just moves on to the next talking head, or the next insight, or whatever. If thereÔÇÖs so much going on in Calvin & Hobbes, maybe the movie should slow down and talk about some of it? WhereÔÇÖs Slavoj ┼¢i┼¥ek┬áwhen you really need him???

There are less philosophical avenues Schroeder could go down, too. He dutifully addresses the fact that this industry is changing, with more and more voices coming from different corners: ÔÇ£There will no longer be another Rolling Stones. There wonÔÇÖt be the Beatles. There wonÔÇÖt be an Elvis Presley. For the same reason, there wonÔÇÖt be another Calvin & Hobbes,ÔÇØ says Bloom County creator Berkeley Breathed, lamenting the fragmentation of the comic strip world. But it might have been worth exploring if maybe Calvin┬áÔÇö whose idiosyncratic style Schroeder credits with helping inspire more diverse, independent voices in the comic world ÔÇö might have had something to do with the resulting fragmentation.

Look, Dear Mr. Watterson is a nice movie. Calvin & Hobbes fans may get a kick out of it. But it falls squarely into the promotional genre of documentary filmmaking┬áÔÇö the same way so many music docs nowadays seem to be just movies about how awesome the directorÔÇÖs favorite band is. It would make a nice supplement to the real thing, maybe a bonus disc when you purchase the Calvin & Hobbes Collection or something. But it never justifies its own existence.

WhatÔÇÖs worse, it squanders several chances to do so. Near the end, Schroeder addresses a particular strip that spoke to him in profound, intangible ways ÔÇö the one he canÔÇÖt forget. In it, we see Calvin sledding down an impossibly high hill, then looking back and sighing in regret. (At least, I think thatÔÇÖs what itÔÇÖs about; the fancy cutting isnÔÇÖt quite clear.) ÔÇ£I can no longer look at it without feeling like IÔÇÖve glimpsed beyond the surface of the comic strip filled with imagination, magic, and joy and adventure and friendship, and seen instead a hint of tremendous disappointment and loss,ÔÇØ the director tells us. And so we wait for him to tell us what that ÔÇ£hintÔÇØ is┬áÔÇö why this speaks so much to him personally. But all he does is note that everybody has their own strip thatÔÇÖs important to them, and moves on. What seemed like a belated emotional connection turns out to be a prime example of why the film never really connects. All weÔÇÖre left with, in the end, are WattersonÔÇÖs bold, beguiling creations, still there for us to behold, their beauty and mystery fully intact.