Penn and Teller arenÔÇÖt the first magicians to make a documentary about art. One of the greatest of films, Orson WellesÔÇÖs F for Fake, is all about art, forgery, and the nature of authorship; it ends the way youÔÇÖd expect a movie made by a magician to end, with a last-minute, unexpected pulling-of-the-rug. Nothing quite so overt happens in TimÔÇÖs Vermeer, a charming and fairly straightforward documentary directed by Teller (the short, quiet one) and produced by Penn (the tall, loud one) about a San Antonio technologistÔÇÖs attempt to re-create a Vermeer painting utilizing a fairly simple mirror technique. But interestingly, it does speak to some of the same things Welles did several decades ago ÔÇö most notable, the way our modern conception of the artist-hero conflicts with the old worldÔÇÖs.

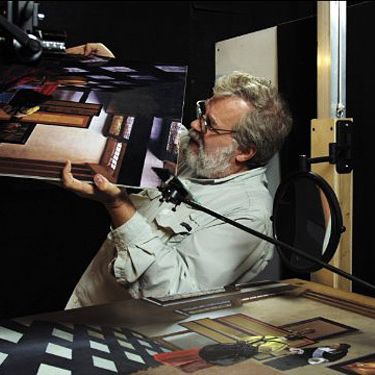

Of course, speculation about the technological doodads Vermeer might have utilized in his work has fueled academic controversy for years. The notoriously photo-realistic quality of his seventeenth-century paintings has led some to posit that he must have secretly used a camera obscura to help him paint. The ÔÇ£TimÔÇØ in TimÔÇÖs Vermeer is Tim Jenison, a Texas-based computer and video engineer who also sees something in the luminosity of these paintings ÔÇö a quality he recognizes from his own work with video cameras. So, he basically devises a mirror-based contraption technique that will allow him ÔÇö a tech guy with absolutely zero painting skill ÔÇö to mimic VermeerÔÇÖs subtle and realistic colors, his unnatural sensitivity to light. Then, to prove that technique works, Tim decides to basically re-paint The Music Lesson. He painstakingly re-creates the room (along with all the needed furniture, d├®cor, and costumes), in a studio, and off he goes.

Do we even want to see a movie arguing that the work of one of the greatest artists of all time could be re-created by a dude with some mirrors and no actual ability to paint? IÔÇÖm not sure. But TimÔÇÖs Vermeer has more on its mind than that. In effect, Penn, Teller, and Jenison are exploring the hard border between technology and art, about the notion that any artist who uses this kind of technological aid must, in some way, be ÔÇ£cheating.ÔÇØ David Hockney actually shows up at one point to lend credence to TimÔÇÖs work and to support the notion that, back in the day, there was no real divide between inventors and artists ÔÇö that innovation went hand in hand with inspiration. If an artist devised an aid that allowed him to paint better, then it was only natural heÔÇÖd embrace it. The cold angles of engineering and the soft edges of creativity were not rivals but allies in the pursuit of beauty and truth. In F for Fake, Welles marveled that the Cathedral at Chartres, which he considered the crowning achievement of Western civilization, was unsigned and anonymous; nobody cared who the genius was who had designed it. In its own way, TimÔÇÖs Vermeer also questions the nature of our conception of the artist as hero ÔÇô as an independent, unreal, almost superhuman spirit.

But thereÔÇÖs even more to it than that. TimÔÇÖs work, which ultimately takes years to complete, changes him in some ineffable way. (It also almost kills him along the way, thanks to an ill-placed patio heater.) TimÔÇÖs Vermeer starts off in a playful fashion, but as he soldiers on, our intrepid, mild-mannered technologist finds himself getting emotional. In the presence of art, something happens. By the time itÔÇÖs over, donÔÇÖt be surprised if youÔÇÖre more in awe of the work of an artist than ever before. Maybe this is Penn and TellerÔÇÖs final, subtle rug-pulling moment: An attempt to demystify the artistic process ends up posing even greater mysteries.