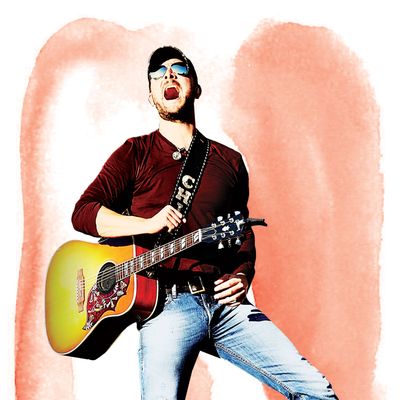

The country singer Eric Church might have written a bad song once or twice, but heÔÇÖs never recorded one. Church arrived in 2006 with a debut album, Sinners Like Me, that was, in a word, sharp: a dozen sharp-witted and sharp-elbowed songs, delivered by Church in his piercing, slightly nasal voice, a sound that comes slicing right at you, like a table saw running through your speaker cabinet. Since then, Church has released a new album roughly every two and a half years, each stronger than the previous, proving himself not just the most consistent male country star of his generation but one of the brightest lights in any genreÔÇöright up there with Kanye West, Beyonc├®, Vampire Weekend, et al. ChurchÔÇÖs new album, The Outsiders, is, in keeping with the pattern, his best yet; itÔÇÖs also his most blustery, with the guitars and the outlaw swagger turned up, as the poet said, to eleven. It opens with the title track, an absurdly bombastic biker-bar anthem that Church likened, in an interview with the website Taste of Country, to both Waylon Jennings and Metallica: ÔÇ£WeÔÇÖre the junkyard dogs, weÔÇÖre the alley catsÔÇà/ÔÇàKeep the wind at our fronts and the hell at our backs.ÔÇØ If youÔÇÖre going to sing a lyric like that and get away with it, you better sing it with conviction, and with a great big wall of noise rearing up behind you. ÔÇ£The OutsidersÔÇØ fits that bill.

Church is from Granite Falls, North Carolina, a town of about 5,000, 60 miles northwest of Charlotte. He began writing songs in his teens, played in bar bands in high school and college, and moved to Nashville following his graduation, spurning his then-fianc├®eÔÇÖs fatherÔÇÖs offer to help him get started in the corporate world. Church told that story in one of the best songs on Sinners Like Me, ÔÇ£What I Almost Was,ÔÇØ a model of fine Nashville handicraft, with its toothsome hooks and string of clever variations on the refrain ÔÇ£I thank God I ainÔÇÖt what I almost was.ÔÇØ Church has co-written all but one of the 48 songs heÔÇÖs released on his albums, which is unusual for a country artist. IÔÇÖd call him a writer first, if he wasnÔÇÖt such a good singer; IÔÇÖd call him a singer-songwriter if that moniker didnÔÇÖt imply a kind of sodden self-regard that Church wants none of. (HeÔÇÖs self-regarding, for sure, but not sodden about it.)

Better instead to say that Church is a Music Row pro who really knows how to put his songs acrossÔÇöhow to croon or drawl or yelp or snarl, to get the biggest payoff from his well-placed punch lines. On The Outsiders there are yuks and tears: funny songs like ÔÇ£Cold One,ÔÇØ a plaint about a girl who stole the singerÔÇÖs heart and, worse, snatched one of his longneck beers, and weepers, like the power ballad ÔÇ£Give Me Back My Hometown,ÔÇØ ChurchÔÇÖs current single. ÔÇ£The JointÔÇØ is sneaky: It sounds at first like an ode to weed but turns out to be a kind of redneck ÔÇ£Norwegian Wood,ÔÇØ a black comedy about a woman who torches the backcountry ┬¡honky-tonk where her husband spends too much time boozing. ÔÇ£The only joint my momma burned was on the rural routeÔÇà/ÔÇàShe parked in old man TaylorÔÇÖs woods so she wouldnÔÇÖt be found out,ÔÇØ Church sings.

ÔÇ£The JointÔÇØ has a woozy sound, a kind of clattering junkyard blues-funk, with a trombone tooting above overdriven bass and ChurchÔÇÖs vocal processed so it sounds like heÔÇÖs warbling through a JewÔÇÖs harp. ChurchÔÇÖs records are the most sonically distinctive in commercial country, balancing rootsy earthiness and digital snap, with a muscled-up rhythm section that is more rock than countryÔÇöand more classic heavy-blues-rock than the eighties arena-rock thatÔÇÖs the current Nashville norm. Credit for the sound goes to Church and Jay Joyce, a Nashville-based guitarist and studio musician who has produced all of ChurchÔÇÖs albums. Joyce is a masterful record-maker, one of the great unsung talents in todayÔÇÖs pop. He is, you might say, the Timbaland to ChurchÔÇÖs Missy Elliott; together, theyÔÇÖre assembling a body of work that expands countryÔÇÖs sonic palette while honoring the genreÔÇÖs core values of structure and storytellingÔÇöcooking up a feast for the ears while making sure that sound never trumps song. Church and Joyce are excellent arrangers with a knack for eccentric touches. (ÔÇ£Springsteen,ÔÇØ ChurchÔÇÖs big No. 1 hit from 2012, found a hook in a ringing five-note piano figureÔÇöhardly the usual country radio hit-bait.) The Outsiders is full of little surprises, unexpected sounds shoved to the front of the mix: In one song, the bass line, bolstered by a groaning trombone, is boosted to such a fearsome rumble you worry your dishes may tumble from the kitchen shelves; in another, a brushed snare drum is close-miked and jacked up so it sounds like wind raking across a leafy hillside.

ChurchÔÇÖs sound isnÔÇÖt all that sets him apart from the pack. Recently, country radio has had a frat-house feel: an undifferentiated corps of party-hearty dudes braying hits about getting drunk and laid. The Outsiders is a rebuke to bro-country clich├®sÔÇönot that Church is averse to partying (cf. his 2011 hit ÔÇ£Drink in My HandÔÇØ), nor to clich├®s per se. From the beginning, he has styled himself as an outlaw, wearing a beard and boots and dark shades and playing to the hilt the rugged but tender bruiser, the role that was pioneered by Waylon Jennings, Merle Haggard, and other ornery refuseniks. On The Outsiders, Church has doubled down on the rebel posturing, although the vibe is, as Church himself might put it, more Metallica than Waylon. Country has tilted toward rock over the past two decades, and Church is determined to out-rock the competitionÔÇönot that tall an order, truth be told. In any case, he makes his case explicit with ÔÇ£ThatÔÇÖs Damn Rock & Roll,ÔÇØ which proffers AC/DC power chords while name-checking the Clash and Nirvana and Janis Joplin, and ÔÇ£Devil, Devil (Prelude: Princess of Darkness),ÔÇØ which has the running time (8:03) and the time-signature changes to match the goofy prog-rock title.

I happen to like those songs, but ChurchÔÇÖs rocker moves feel a bit more stilted than his country ones. He is, at his essence, a great country singerÔÇöa genre artist par excellence. Country, like all genre music, is often High Hackwork: ItÔÇÖs the art of making clich├®s pay, again and again, of tweaking the conventions ever so slightly or embodying the conventions with such force or finesse that you make them feel fresh. In the best moments on The Outsiders, Church does just that, revitalizing the familiar through sheer charisma and the ideally deployed chord or couplet. The ballad ÔÇ£A Man Who Was Gonna Die YoungÔÇØ is a variation on a favorite country theme: the desperado redeemed by the love of a good woman. But in ChurchÔÇÖs hands, it turns into something deeper, a song about agingÔÇöabout sliding, more gently than you imagined you could, into middle age:

In the mirror I saw my surprise

Who knew gray hairs liked to hide

On a head didnÔÇÖt think heÔÇÖd live past 30

If I make it 30 more, itÔÇÖs the brown that youÔÇÖll be looking for

As you run your fingers through it

And say, ÔÇ£Slow down, honey.ÔÇØ

My favorite song on The Outsiders, ÔÇ£Like a Wrecking Ball,ÔÇØ is also another smart variation on standard fare: the road-weary musicianÔÇÖs ode to his gal at home. ItÔÇÖs one of ChurchÔÇÖs deftest songs; itÔÇÖs definitely his hottest, as sexy an ode to connubial booty-calling as any on Beyonc├®ÔÇÖs new album. HereÔÇÖs Church receiving a selfie from his wife: ÔÇ£You, look at you, send me one more shotÔÇà/ÔÇàSittinÔÇÖ on the bathroom sinkÔÇà/ÔÇàDamn, you really turn me onÔÇà/ÔÇàPainting your toenails pink.ÔÇØ Church sings those words over a warm, almost soul-ballad-like groove, nudged forward by a piping Hammond organ. It sounds great, especially at high volume. In fact, another lyric from ÔÇ£Like a Wrecking BallÔÇØ could serve as ChurchÔÇÖs mission statement for this album, which is best experienced not plugged into earbuds but blasted, the old-fashioned way, through a pair of speakers with sturdy subwoofers. ÔÇ£I want to rock some Sheetrock,ÔÇØ Church sings. ÔÇ£Knock some pictures off the wall.ÔÇØ

*This article originally appeared in the February 3, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.