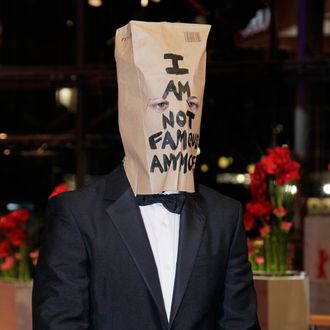

A bullwhip. A pink ukelele. A pair of pliers. A bowl of Hershey kisses. They’re all laid out neatly on a table in front of me in this small Los Angeles art gallery, where I stand alone, waiting. A young, hesitant woman emerges from behind a curtained-off room, looking surprised to see me. “Sorry,” she says. “Um … we’re not ready.” Before the black curtain falls back into place behind her, I spy a figure in the next room, a man wearing a tuxedo with a brown bag pulled over his head, onto which are scrawled the words “I AM NOT FAMOUS ANYMORE.”

It’s only the briefest glimpse, but anyone who’s been online this past week would immediately recognize the masked figure as Shia LaBeouf. The actor made headlines last weekend when he stormed out of a Berlin press conference for his new film Nymphomaniac after muttering a weird, plagiarized line about sardines; he’d later show up to the premiere of the film wearing that striking tux-and-brown-bag ensemble, only the most recent incident in a string of odd behavior since LaBeouf was accused of plagiarism in December for lifting a Daniel Clowes comic to make his short film Howardcantour.com.

LaBeouf has spent the last few weeks doubling down on that episode, tweeting apologies that were clearly appropriated from other famous mea culpas, and his presence in the art gallery is just the latest continuation of the story: For a performance piece entitled #IAMSORRY, LaBeouf will be “in situ” at the gallery for the next week, and a brief statement about the show says he will receive visitors from 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. each day.

Just not right now. “Sorry,” the girl says again, ushering me out front and closing the door behind her.

The two security guards posted outside the gallery turn and smirk. “We’re still working out the kinks,” one says. “Stick around.” It’s noon, and I’m the third person who’s shown up to meet with LaBeouf; while I have no doubt that there will eventually be a line around the block to rival Dumb Starbucks, so far, I’ve only been preceded by two other journalists. One of them, a furrowed-brow Brit who writes for the Independent, is debating whether he should get in line again. “I don’t think I did it right the first time,” he says, unwilling to tell me anything else about his encounter: “You should just experience it yourself.” A few minutes later, as the line to get in has suddenly swollen to fifteen, the security guard wands me, mutters something into his walkie talkie, and sends me in again.

This time, the girl is standing at the table from the start, expecting me. She indicates the props and says, “You can pick one and take it into the next room.” For no real reason, I choose the pink ukelele.

And then I walk into the next room. It’s smaller and darkly lit, and Shia is sitting down at a small wooden table, palms laid flat, bag on head. There’s a chair opposite him, and I take it. He stares at me through the tiny eyeholes he’s cut into the bag.

“Do you want to talk?” I ask. No response. He just sits there, staring.

I try a lighter tack: “Do you play the ukelele?” Still nothing.

Instead of talking, then, we sit in silent communion, Shia staging his own version of the famous Marina Abramovic performance piece “The Artist Is Present.” I’d come prepared with a few questions, not quite knowing what to expect; those all seem moot now. All I’m meant to do is sit there, maintain eye contact, and divine a charge.

Unless you’re in a Nicholas Sparks novel, you rarely spend minutes on end staring into another person’s eyes, but as it happened, I’d had practice: Just a few days before, I was at a movie premiere after-party where a man I’d only just met announced himself to be a “soul healer.” Brash and heavily Bronx-accented, he offered to stare into my eyes for an impromptu reading, and there were free drinks at this party, so I said yes. He held my gaze for a full minute, then finally said, “You need to be worldwide. If you work with me, I can help you get there.” He paused, scrutinized me further, then asked hopefully, “Are you a producer?”

I think of him briefly while I keep eye contact with Shia, but mostly, I stay present and friendly, trying to figure out Shia’s mood from what little I can see of his face, and absently strumming the ukelele while we stare at each other. As I flick those strings, the sound of the ukelele so pretty that it belies my total inexperience with it, I notice that Shia’s big brown eyes have grown watery.

After a moment, I put the ukelele down and offer him an upturned palm. None of my other questions have produced any sort of reaction from him, but I know this one will be different. “Do you want to hold my hand?” I ask.

A minute later, he puts his hand in mine and leaves it there.

And so I sit across from Shia LaBeouf with our hands intertwined and resting on the pink ukelele, the actor’s gaze constant and growing wetter until tears start to fall from his eyes, sliding down the brown paper bag over those messy, scrawled capital letters. He rubs my hand with his thumb as he weeps.

Eventually, it’s time to go. We unclasp hands and I indicate the ukelele. “Are you sure you don’t want to play?” I say, and his wet eyes twinkle. He nods, just barely, and I’m pretty sure he’s smiling. And then I rise from my seat and leave him there, the brown bag over his face streaked with tears as he prepares to receive the next visitor. The mousy girl from before reemerges, and I’m ushered down a hallway and out of the gallery, the surreal #IAMSORRY experience concluded.

As I stand in the alley afterwards, I pull out an audio recorder and mumble some notes, and I’m sort of surprised to find my voice so tremulous. Was I actually moved? Was he? Or was it all just a put-on, and this actor was merely crying in front of me because he’d seen Abramovic do it multiple times during her own famous staring contests? After all of Shia’s willful acts of plagiarism, it’d certainly be apropos.

Maybe the truth was somewhere in the middle. An hour later, a friend texts me after his own encounter. He’d waited for a while in line behind a bunch of tweeting assholes, and when the time came to enter, “I brought him a flower and put it on the table and said, ‘I’m not like them.’” How did Shia respond? “He started crying.”