Normcore: Fashion for Those Who Realize They’re One in 7 Billion

Sometime last summer I realized that, from behind, I could no longer tell if my fellow Soho pedestrians were art kids or middle-aged, middle-American tourists. Clad in stonewash jeans, fleece, and comfortable sneakers, both types looked like they might’ve just stepped off an R-train after shopping in Times Square. When I texted my friend Brad (an artist whose summer uniform consisted of Adidas barefoot trainers, mesh shorts and plain cotton tees) for his take on the latest urban camouflage, I got an immediate reply: “lol normcore.”

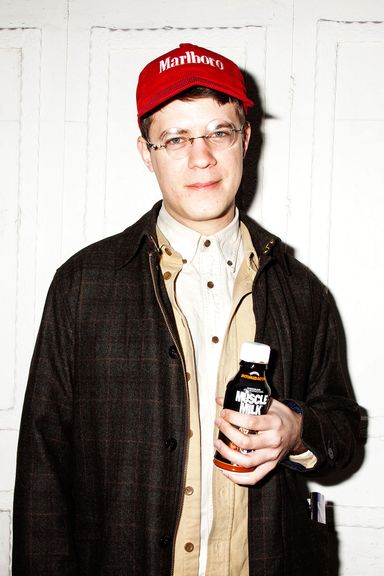

Normcore—it was funny, but it also effectively captured the self-aware, stylized blandness I’d been noticing. Brad’s source for the term was the trend forecasting collective (and fellow artists) K-Hole. They had been using it in a slightly different sense, not to describe a particular look but a general attitude: embracing sameness deliberately as a new way of being cool, rather than striving for “difference” or “authenticity.” In fashion, though, this manifests itself in ardently ordinary clothes. Mall clothes. Blank clothes. The kind of dad-brand non-style you might have once associated with Jerry Seinfeld, but transposed on a Cooper Union student with William Gibson glasses.

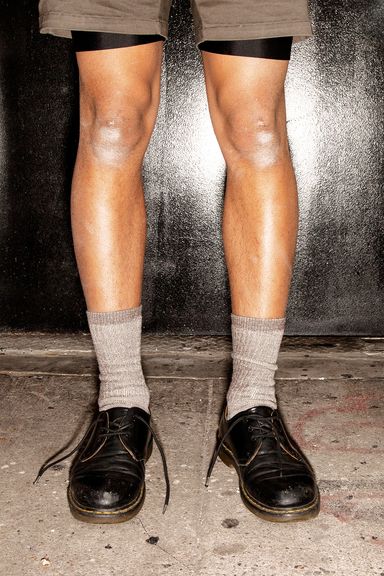

At first, I spotted just occasional forays into normcore: the rare cool kid wearing clothes as lukewarm as the last sips of deli coffee—mock turtlenecks with Tevas and Patagonia windbreakers; Uniqlo khakis with New Balance sneakers or Crocs and souvenir-stand baseball caps.The look also cropped up on my social-media feeds, on Internet “It” kids’ Instagrams and Tumblrs. Internet-inspired artist Jeanette Hayes (who’s created work on behalf of Proenza Schouler and Alexander Wang) was layering white athletic socks with strappy stilettos, and posing for selfies in a Yankees cap and juniors-department denim. VFILES host and casting director Preston Chaunsumlit wore white nurse clogs for several seasons running. And Devonté Hynes of Blood Orange amassed a collection of off-brand New York ball caps, which he paired with turtlenecks, sweatpants, and boxy jeans. Showing up for an interview with Fader at the Empire State Building, Hynes looked, wrote the reporter, “like a tourist.”

By late 2013, it wasn’t uncommon to spot the Downtown chicks you’d expect to have closets full of Acne and Isabel Marant wearing nondescript half-zip pullovers and anonymous denim. Magazines, too, had picked up the look. T noted the “enduring appeal of the Patagonia fleece” as displayed on Patrik Ervell and Marc Jacobs’s runways. Edie Campbell slid into Birkenstocks (or the Céline version thereof) in Vogue Paris. Adidas trackies layered under Louis Vuitton cashmere in Self Service. A bucket hat and Nike slippers framed an Alexander McQueen coveralls in Twin. Smaller, younger magazines like London’s Hot and Cool and New York’s Sex and Garmento, were interested in even more genuinely average ensembles, skipping high-low blends for the purity of head-to-toe normcore.

Jeremy Lewis, the founder/editor of Garmento and a freelance stylist and fashion writer, calls normcore “one facet of a growing anti-fashion sentiment.” His personal style is (in the words of Andre Walker, a designer Lewis featured in the magazine’s last issue) “exhaustingly plain”—this winter, that’s meant a North Face fleece, khakis, and New Balances. Lewis says his “look of nothing” is about absolving oneself from fashion, “lest it mark you as a mindless sheep.”

“Fashion has become very overwhelming and popular,” Lewis explains. “Right now a lot of people use fashion as a means to buy rather than discover an identity and they end up obscured and defeated. I’m getting cues from people like Steve Jobs and Jerry Seinfeld. It’s a very flat look, conspicuously unpretentious, maybe even endearingly awkward. It’s a lot of cliché style taboos, but it’s not the irony I love, it’s rather practical and no-nonsense, which to me, right now, seems sexy. I like the idea that one doesn’t need their clothes to make a statement.”

One of the first stylists I started bookmarking for her normcore looks was the London-based Alice Goddard. She was assembling this new mainstream minimalism in the magazine she co-founded, Hot and Cool, as early as 2011. For Goddard, the appeal of normal clothes was the latest thing: “Styling is about showing different types of clothing in a new way,” she says, “which normally means taking something—an item, a character or an idea—that I find kind of ugly and gross, and making it good.”

Goddard’s initial interest in normcore was in part a reaction to the fashion status quo. One standout editorial from Hot and Cool no. 5 (Spring 2013) was composed entirely of screenshots of people from Google Map’s Street View app. Goddard had stumbled upon “this tiny town in America” on Mapsand thought the plainly-dressed people there looked amazing. The editorial she designed was a parody of contemporary street style photography—“the main point of difference,” she says, “being that people who are photographed by street style photographers are generally people who have made a huge effort with their clothing, and the resulting images often feel a bit over fussed and over precious—the subject is completely aware of the outcome; whereas the people we were finding on Google Maps obviously had no idea they were being photographed, and yet their outfits were, to me, more interesting.”

The Internet is where all conversation about normcore seems to converge. New media has changed our relation to information, and, with it, fashion. Reverse Google Image Search and tools like Polyvore make discovering the source of any garment as simple as a few clicks. Online shopping—from eBay through the Outnet—makes each season available for resale almost as soon as it goes on sale. As Natasha Stagg, the Online Editor of V Magazine and a regular contributor at DIS (where she recently wrote a normcore-esque essay about the queer appropriation of mall favorite Abercrombie & Fitch), put it: “Everyone is a researcher and a statistician now, knowing accidentally the popularity of every image they are presented with, and what gets its own life as a trend or meme.” The cycles of fashion are so fast and so vast, it’s impossible to stay current; in fact, there is no one current.

Emily Segal of K-HOLE insists that normcore isn’t about one specific aesthetic. “It’s not about being simple or forfeiting individuality to become a bland, uniform mass,” she explains. Rather, it’s about welcoming the possibility of being recognizable, of looking like other people—and “seeing that as an opportunity for connection, instead of as evidence that your identity has dissolved.”

K-HOLE describes normcore as a theory rather than a look; but in practice, the contemporary normcore styles I’ve seen have their clear aesthetic precedent in the nineties. The editorials in Hot and Cool look a lot like Corinne Day styling newcomer Kate Moss in Birkenstocks in 1990, or like Art Club 2000’s appropriation of madras from the Gap, like grunge-lite and Calvin Klein minimalism. But while (in their original incarnation) those styles reflected anxiety around “selling out,” today’s version is more ambivalent toward its market reality. Normcore isn’t about rebelling against or giving into the status quo; it’s about letting go of the need to look distinctive, to make time for something new.

The demographic leading the normcore trend is, by and large, Western Millennials and digital natives. Stylist-editors like Hot and Cool’s Alice Goddard and Garmento’s Jeremy Lewis are children of the nineties, teens of the aughts. The aesthetic return to styles they would’ve worn as kids reads like a reset button—going back to a time before adolescence, before we learned to differentiate identity through dress. The Internet and globalization have challenged the myth of individuality (we are all one in 7 billion), while making connecting with others easier than ever. Normcore is a blank slate and open mind—it’s a look designed to play well with others.

*This is an expanded version of an article that ran in the February 24, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.