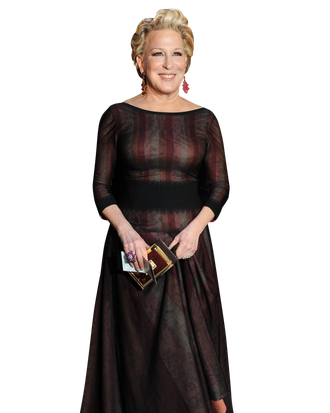

In her 1980 book A View From a Broad (re-released last week), Bette Midler wrote what she hoped would be the last word on playing the Continental Baths, the infamous gay bathhouse where she got her New York beginnings: “I did not perform in the middle of a steam room, but in the poolside cafe next to the steam room … And by the way, I never laid my eyes on a single penis, even though I was looking really hard.” That being said, then, the Divine Miss M has a lot more to say about the less-explored early parts of her career, which she shared with Vulture during a recent conversation.

Let’s talk about your earliest influences.

Nina Simone was also a gigantic influence on me. When I was a little girl, she had a record out called “Children, Go Where I Send You,” which was one of the greatest records I had ever heard in my life. I used to stand in front of the radio and belt that at the top of my lungs. I loved her. And I met her! She came to a show of mine, and we sat together, and we both shed lots of tears. And Ethel Waters, I adored her. A friend of mine introduced me to Ethel Waters. He played a record for me, “Suppertime,” and she breaks down and cries in the middle of it, and it is so moving and heart-wrenching. It kind of opened a door in my mind that you didn’t have to have the biggest voice in the world. You didn’t have to have the most beautiful voice in the world. What really mattered was that it pierce your heart. She taught me that. And Nina Simone indicated that music didn’t have to be three-chord music, it could be enormously complex essays. Musical essays. They could be full of bitterness and heartache and hope and all of the range of human emotions. It didn’t just have to be, “Baby, baby, baby/Love me, love me, love me.” And that was a big lesson. A big, big lesson.

What about Sophie Tucker? When you came up with the character of Soph, she was based on Sophie Tucker?

I did see her when I was a very young girl. She came to Hawaii, one of the first nightclubs I had ever been to. But because I wasn’t from the continental United States, I was in Hawaii, where these seriously kind of Jewish things didn’t occur, I didn’t really get it. I was also too naïve to understand what the lyrics were about. She sang slightly risqué songs, and it was totally and completely charming. I never forgot it. And as I grew older, I discovered a whole series of women who were very similar in tone, like Belle Barth and Rusty Warren and Frances Faye. And Mae West.

So when I made up the character named Soph, and we put these sort of terrible jokes in her mouth. She was kind of a throwback, a little bit of an homage to those big-hearted broads who sang and told risqué stories. I like to throw my head back and scream with laughter, but I didn’t have a way to put those jokes in my mouth. Some of them were so appalling that if I took credit for them, I felt that I would be diminished in some way. So I made up a character that I felt that I could hide behind. And people recognized her from their own childhood. Their parents brought home those records, in brown paper wrappers, you know? And they would send their children up [to bed] and they would have cocktails and listen to those records and scream. But that wasn’t my interest. I came to the city because I wanted to be a dramatic actress, and I think I was only living on a fantasy. I didn’t really know what any of it meant. I was out in the Pacific Ocean daydreaming.

When you were first starting to audition, what song did you use?

“Pirate Jenny,” oh my God! That was the song I got all my jobs with. “Ah! You’re hired.” It wasn’t a standard melody, but it had a lot of power behind it. The one little year that I managed to survive college [at the University of Hawaii], they had done a production of Threepenny Opera, and it was just mind-boggling. But when I finally got to the city, the brew! It was overwhelming, because the entertainment choices were enormous. I was in the theater for a few years, and I had a good time, but I was struggling to make my way. I was shut out a little bit. So I turned to music, and I never really thought of that as a main thing.

And you were working as a hat-check girl at the time?

When I first came to the city, there was a place called Salvation, which was a disco, which had formerly been Café Society. It was 1 Sheridan Square, and it was a kind of a liberal bastion for folk singers and people of color, and uptowners would come to meet downtowners. By the time I got there, and I was the hat check girl, Jimi Hendrix was playing, and he was the house band for a second or two! That was kind of fabulous. It was the middle ‘60s, and there was a lot of stuff I tucked into my back pocket, tucked into my mind, like the girl groups of the ‘60s, who I loved, but I didn’t exactly take seriously. When I saw Tina Turner, the whole magic that Ike put together, I used to go from borough to borough to catch her. I went to some major dives! Janis [Joplin] had major power, too. I would always rush down to see her. You know those days when you would sit in a balcony and listen to her, and the balcony would shake. And you thought, “This is the end of me. This is how I’m going to go.”

Where did you do your very first shows, before the Baths? At Hilly’s?

At Hilly’s on West 9th Street. Hilly’s was Hilly Kristal’s club before CBGBs, and I didn’t know he had that in him! It really was a surprise that he ended up sort of as the godfather of punk-rock, because what he had there on 9th Street, it really was a little bit traditional. He had a piano player, Bill Cunningham, and he was one of the greatest piano players I ever heard. I don’t know what happened to him. I used to look for him from time to time, but I never found him again. I was flying by the seat of my pants in those days, and I liked Hilly. And when I was at the Baths, one of Laura Nyro’s best friends was my lighting man. He introduced me to her music, and he introduced me to her, and of course, I never really recovered from that, because she was the epitome of a certain kind of New York woman. Her stuff was so heartbreaking, so soulful. And in those days, when she and Joni Mitchell were working, their music was played constantly, you really felt it in the air. The atmosphere was dense with it. Both of those women, I sang their music for years. I never recorded any of it, but I sang it for audiences for years.

So just being around other New York musicians was pivotal for you.

It was as if New York was the place to be. It was the most exciting thing to make, music. Everybody wanted to be in it, everyone was looking for a place in it, and my place chose me, so that’s what I stuck with. But I was always interested in what other people were doing. I’m a little bit of a technician, so I kind of like craft, and I do like people who can really play and really sing, who can really hit the high notes. I like all that.

But I also like people who have something to say. I love the poetry of it. And I really think that the folk era really kicked it off for people, you know? I think Bob Dylan and all those people who were working at that time made you feel that if you had a poet’s soul, if you had something to say, and you knew a couple of chords, you could set it to music and you could make a living. Every day you would jump out of bed and wonder what was going to happen to you next. And I listen to everything. I don’t have any prejudices about music. I don’t discriminate. I like all of it. I think people making music and making art is the most positive thing that human beings do. Anyone who sits down and tries, I totally give them props, because I know how hard it is.