Strangely, what I thought about first was the parrot:

a royal Paramaribo parrot, who knew only the blasphemies of sailors but said them in a voice so human that he was well worth the extravagant price of twelve centavos.

Purchased extravagantly, educated extravagantly, the bird came to know not only nautical profanity but also French (ÔÇ£like an academicianÔÇØ), Latin, the Gospel according to Matthew, Liberal Party slogans, how to bark like a mastiff when being burgled, and how to refer to itself: asÔÇöofficiously, proudly, possibly snidelyÔÇöÔÇ£Royal Parrot.ÔÇØ And yet, despite this lavish education, the ungrateful creature escapes its home, alights in the branches of a nearby mango tree, and thereby causes the death, by parrot, ladder, senescence, and gravity, of Dr. Juvenal Urbino, in the opening chapter of Gabriel Garc├¡a M├írquezÔÇÖs Love in the Time of Cholera.

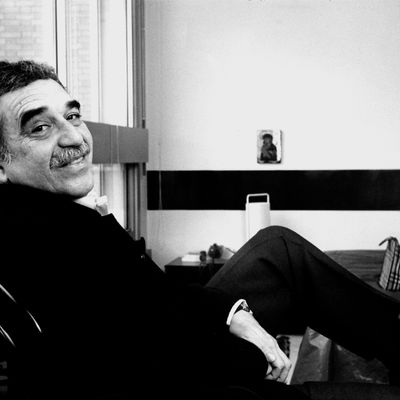

ÔÇ£It was a memorable death, and not without reason.ÔÇØ So wrote the author; and so, too, his own death yesterdayÔÇönot because of its manner (at home, at the age of 87, after a slow decline that included lymphatic cancer and dementia) but because of the life that preceded it. I will skip the biographical details, readily available elsewhere, except to note two that strike me as particularly salient to his writing. First, Garc├¡a M├írquez was born in Aracataca, near the Caribbean coast of Colombia. Second, he worked as a journalist, not only before he found worldwide fame with One Hundred Years of Solitude but throughout his career.

As it happens, I read the journalism first. Sixteen years old, newly smitten with Defoe and obsessed with shipwrecks, I chanced on the story of a Colombian sailor who spent ten days adrift in a life raft without food or water after his Navy vessel, overloaded with contraband, capsized en route from Alabama to Cartagena. That was The Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor, which García Márquez ghostwrote in 1955, before he became famous. The tale, in his telling, is as straightforward and spare as the situation. Man, raft, ocean: realism, without the magic.

ButÔÇöghostwrote. The Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor is haunted by the ghost of Gabriel Garc├¡a M├írquez Future. Already there is the elemental, almost mythical crisis. Already there is the reckoning with solitude and the proximity of death. And already there is the understanding that no matter how passionately and idiosyncratically we live, we are the playthings of larger forces, from the illicit machinations of the military to the indifferent swell of the ocean. Of the authorÔÇÖs enduring themes, the only major one missing here is love.

The love would appear in the fiction, abundantly, as would other absent elements, including the famous magic. It is not so much that magic is everywhere in these books as that it is always somewhereÔÇöand, being magic, always startling. A corpse fails to decay. A ghost wants a glass of water. An angel is forced down to earth by bad weather. A priest, tending in the opposite direction, levitates six inches off the ground. All this is delivered as matter-of-factly as the mail; until Murakami came along, Garc├¡a M├írquez had the best poker face in literary history.

Two things keep the magic tethered to the real. The first is that Garc├¡a M├írquez never stopped reporting. His beat was the Caribbean coast of Colombia, more broadly all of the Caribbean, more broadly still the entire continent and its position in the world. His fallen angels and levitating priests are never more than those airy six inches from the lived history of Latin America, starting with colonialism and slavery and continuing through to the wars, coups, dictatorships, disappearances, and massacresÔÇöbacked by Western powers, ignored by Western powers, or bothÔÇöthat unfolded during his own lifetime. In his fiction, Garc├¡a M├írquez took a stand against two of the regionÔÇÖs chronic diseases, machismo and violence. But he also took a stand for the region, for its right to tell its own stories, in its own way, for its own ends.

The other and ultimate reason the magical realism works is that everything García Márquez did works. He could do funny and lyrical and coarse and tender and dirty. He could do men and, mirabile dictu, women. He could do sentences like the tropics do forests: earthy and lofty, noisy and colorful, strewn with rare species, dense with life. And he could tell a story as well as any writer ever. The hell with putting a gun in the first act; he could put an entire firing squad in the first line, amble away to prehistory and a pretty little river in the next clause, and come back on the last page to make you cry.

And, of course, he could find the seam of fiction in the rational worldÔÇöthe places where life shimmers, like a highway in the heat. Take that parrot in Love in the Time of Cholera. Is it magic or is it realism? Is it just a bundle of avian instincts? Or is it a sentient being, thinking about the gospel, conjugating verbs, pranking its owner, seeking its freedom? Better still, take parrots in general. What kind of self-respecting unmagical world would be home to such magic-marker birds, birds that know how to talk and that live eighty years and more?

For a minor character, if it can even be called that, what an apposite creation that parrot turned out to be. Colorful, extravagant, blasphemous, polyglot, erudite, protective, and mischievous, with an unfathomable mind and an extraordinary voice: it was Garc├¡a M├írquez himself, trapped in another kind of body, as happens sometimes┬áin fairy tales as myths. No wonder it was what came back to me first when I learned that he had died. The┬áparrot┬áwas followed soon after by its owner, Juvenal Urbino; by the lovers, Florentino Azizo and Fermina Daza; by the shipwrecked sailor; by the General; by seven generations of the Buend├¡a family. That is the magic not in Garc├¡a M├írquezÔÇÖs books, but of them: that the characters he created could return to me as if bearing the sad news themselvesÔÇöas if once they really had lived; as if they still did.