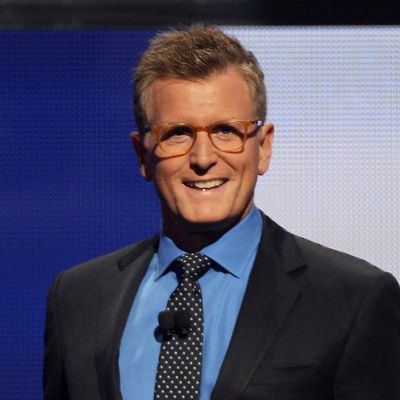

Five months ago, Fox network chief Kevin Reilly announced an ambitious plan to cancel network TVÔÇÖs decades-old pilot season, resulting in a slew of stories (including a very recent one in New York Magazine) about how it represented a possible sea change for the crusty old broadcast business. Today, it was Reilly who got canceled, or maybe canceled himself: The network issued a press release saying that the veteran TV exec, whoÔÇÖd been at Fox since 2007 and had previously run NBCÔÇÖs entertainment division, would be exiting at the end of June.┬áItÔÇÖs possible ReillyÔÇÖs no-pilot pledge played a part in his departure, that his attempt to do Something Big scared his bosses. More likely, he was doomed by something far more pedestrian: His bosses, including 21st Century Fox head Rupert Murdoch, werenÔÇÖt happy with FoxÔÇÖs disastrous ratings performance of late and didnÔÇÖt think ReillyÔÇÖs upcoming crop of new shows would be enough to turn things around. Reilly may have had a very specific, even logical plan for moving Fox forward. Those above him, however, either didnÔÇÖt share his vision, or didnÔÇÖt believe in it enough to convince him to stay.

Officially, Reilly and his boss, Fox Networks Group CEO Peter Rice, are calling this a voluntary departure, saying in a press release that theyÔÇÖd been talking about Reilly leaving for ÔÇ£a while.ÔÇØ And in a brief phone call with me Thursday afternoon, Reilly repeated that notion, saying he had ÔÇ£been having conversations in the abstract over the last 12 monthsÔÇØ about a post-Fox career. ÔÇ£I was already beginning to thinkÔÇØ about moving on, he said. And yet itÔÇÖs worth noting that, as recently as April, Reilly seemed very much invested in his current gig. I spent upwards of two hours with Reilly discussing his vision for the network ÔÇö and not just blowing up pilot season. Reilly was animated throughout our conversation, wary of the changes gripping the TV business right now, and clearly not happy with FoxÔÇÖs spring stumble in the ratings. (ÔÇ£WeÔÇÖre skidding into the finish,ÔÇØ he said dryly.) He did not seem like a man who expected to be leaving his job anytime soon; in fact, he spoke about how his pilot plan had been embraced by his bosses and would be judged over the long term. ÔÇ£I think one of the things I like best about the company I work at is thereÔÇÖs not a lot of decision by committee,ÔÇØ Reilly said. If ÔÇ£a year or two down the line if this thing doesnÔÇÖt work, [then] someone will say, ÔÇÿWell, that was a bunch of hot air.ÔÇÖÔÇØ On Thursday, Reilly said his confidence a month ago was simply about him doing his job at that moment. ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm here until IÔÇÖm not here, whether thatÔÇÖs a month from now or a year from now,ÔÇØ he said.

And yet, industry insiders werenÔÇÖt completely shocked Thursday when the news of ReillyÔÇÖs exit broke. ThatÔÇÖs because, just weeks after Reilly talked to us, reports started trickling in that Rice and Reilly werenÔÇÖt seeing eye to eye on some decisions. Multiple sources tell Vulture that, during the late April/early May process of deciding what FoxÔÇÖs new schedule would be, Reilly had, almost reluctantly, chosen to order 13 more episodes of the critically loved freshman comedy Enlisted. He also made the no-brainer call to bring back the J.J. AbramsÔÇôproduced modest hit Almost Human for a second season. And yet, according to multiple accounts, Rice essentially vetoed ReillyÔÇÖs decisions in both cases. RiceÔÇÖs thinking on Enlisted, according to people familiar with the situation, was that the show wasnÔÇÖt likely to ever be a big hit, so why should the network sink more money into it, even if the show came from in-house production company 20th Century Fox TV? (The fact that Reilly had previously indicated zero interest in Enlisted made it hard for him to dispute RiceÔÇÖs logic.) As for Almost Human, while the showÔÇÖs ratings might have warranted renewal, it was a very costly series produced by a competing showbiz behemoth (Time WarnerÔÇôowned Warner Bros. TV). If WBTV wasnÔÇÖt going to cut its price for the show, Rice, according to sources, saw no season to bring back a marginal hit, particularly since Reilly had already gone to bat for, and renewed, two low-rated comedies produced by outside companies (The Mindy Project and Brooklyn Nine-Nine).

While declining to get too specific, Reilly confirms that he and Rice went a couple rounds on some projects during the pre-upfront period. But he disputed the idea that their relationship had soured: While we werent always in lock step on decisions, Reilly said he and his boss were never at cross-purposes  It wasnt like we were fighting. Its possible, of course, that the reports of tension, filtered through agency and studio sources, may have made it appear Rice and Reilly were more at odds than they were. Top-level bosses such as Rice often overrule underlings, and its not news. Its unlikely Reilly quit because he lost a couple of small battles with Rice. But the gossip from upfronts may hint  and this is just spit-balling a theory, not a declaration of fact  that Reillys exit may have less to do with fallout from his desire to change how TV shows are made, and more to do with other tensions between Rice and Reilly revolving around financial decisions.

Network TV is increasingly less a business about the weekly ratings race and more a business about how much money networks can make by owning, controlling, and exploiting individual properties. A modestly rated procedural on CBS thatÔÇÖs also owned by CBS (say, Hawaii Five-0) can end up making a lot more money for a network than a higher-rated show on NBC or Fox that the network doesnÔÇÖt own outright (see: The Blacklist). Fox has produced some really good TV under Reilly, and some hits, but massive profit-generating machines havenÔÇÖt been so plentiful. Reilly came up in Hollywood as a development executive, and as such, his passion has always been focused on making the best shows possible (not for nothing, he helped birth both The Sopranos and The Office). But two years ago, Rice promoted Reilly to chairman of Fox, a position that called for Reilly to think more like a coldhearted businessman and less like a lover of good TV. ItÔÇÖs possible Rice thought Reilly didnÔÇÖt transition to that new role quickly enough, or maybe Reilly no longer had a desire to be the guy who counts beans first.

During our brief chat Thursday, Reilly betrayed not a hint of animosity toward Rice or Fox. He seemed to be at peace with whatÔÇÖs happened and ready to move on. He noted that between Fox and NBC, heÔÇÖs run a broadcast network for the better part of a decade, and that his mind had ÔÇ£started to wanderÔÇØ to other job possibilities. ÔÇ£This was an important stop on the road for me, [but] I never thought it was the last stop,ÔÇØ he said. And something else Reilly told me last month suggests that maybe he was at least somewhat mentally girding himself for a change. I pushed him about the possibility that he wouldnÔÇÖt be at Fox long enough to see his pilot season shakeup plan come to fruition. ÔÇ£Will you survive to see if these changes work?ÔÇØ I asked Reilly. ÔÇ£I hope so,ÔÇØ he told me. But lack of job security, he noted, ÔÇ£goes with the territory of this job. It is a ÔÇÿwhat have you done for me latelyÔÇÖ job. IÔÇÖve done a version of this now for almost seven years at Fox, and four before that at NBC. I get out of bed to win in the morning, to put on great television, to do the best I can in this position ÔǪ Do I sit there every day just trying to figure out [whether to] do something I donÔÇÖt believe in because maybe it buys me a little more time in my job? I donÔÇÖt. If at some point in time IÔÇÖm done doing this, or IÔÇÖm invited to no longer do it anymore, IÔÇÖve accomplished a lot of what I wanted to accomplish with this job. IÔÇÖm not worried about not working anymore.ÔÇØ