In recent years, George Takei, once known mainly as the guy who played Sulu on the original Star Trek in the ÔÇÿ60s, has become a fixture on talk shows and just about everywhere else ÔÇö partly because of his out-and-proud status as a gay American, and partly because of his willingness to speak about his familyÔÇÖs imprisonment in a World War II Japanese-American internment camp. HeÔÇÖs a great spokesman for these causes ÔÇö funny, self-deprecating, earnest but not sanctimonious. But he also bridges an important gap: He can speak both to AmericaÔÇÖs sordid, bigoted past and to its fundamental capacity for goodness. HeÔÇÖs a man who was imprisoned by his country ÔÇö literally, for his ethnicity, and figuratively, for his sexual orientation. And yet, here he is, persistent, happy, driven. The very picture of the countryÔÇÖs can-do spirit.

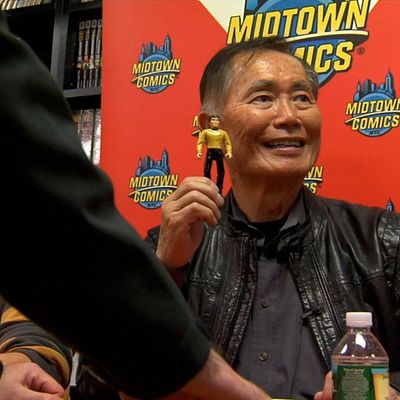

Jennifer M. KrootÔÇÖs To Be Takei is the kind of documentary thatÔÇÖs smart enough to step back and let its charming subject take over. It wonÔÇÖt break new ground, but itÔÇÖs not lazy or generic. Kroot jumps back-and-forth through TakeiÔÇÖs career, deftly juggling the various pieces of his story. We see Takei and his longtime partner and now-husband, Brad, as they go about their lives and put in appearances at various conventions, fund-raisers, graduation ceremonies, keynote speeches, etc. We see footage from TakeiÔÇÖs career, including his early appearances on the ÔÇ£Howard Stern Show,ÔÇØ back when he was still closeted. (Stern, interestingly, comes across as a prime example of a figure from TakeiÔÇÖs life whose attitudes have shifted over the years.) We see TakeiÔÇÖs various TV and film appearances, speaking to the difficulties of finding work as an Asian-American actor in Hollywood. Along the way, Takei himself narrates the heartbreaking story of his familyÔÇÖs internment during World War II. At one point, he notes that his family was given a chance to leave the camps if they would just sign an oath relinquishing their loyalty to the Emperor of Japan. TakeiÔÇÖs parents refused, because they had never been loyal to the Emperor of Japan; the oath was the nationalistÔÇÖs version of the ÔÇ£When did you stop beating your wife?ÔÇØ question. And so, in prison they remained.

This could have easily been a platitudinous, self-important mess, but Kroot does a couple of very savvy things here. First, she occasionally, subtly undercuts TakeiÔÇÖs good-natured sense of humor to show the drive and anger still living within him. He gets very upset, for example, whenever anyone refers to homosexuality as a ÔÇ£lifestyle,ÔÇØ as opposed to an ÔÇ£orientationÔÇØ ÔÇö even when his own husband does it.┬á His years-long beef with William Shatner, which occasionally bubbles up in funny ways in the pop-cultural spotlight, is both funny and troubling: Shatner seems totally oblivious to TakeiÔÇÖs presence, barely pretending to know him. ItÔÇÖs weird, and we sense that Takei, while he laughs about it, is secretly quite troubled by it.

But most important, Kroot uses TakeiÔÇÖs ubiquity as her secret weapon. She cuts between various public appearances in which the actor-activist gives the same speeches about his internment, and then about his life as a closeted gay man. Most documentaries, at least non-political ones, might try to paper over the fact that their subject keeps giving the same speech over and over again, in an attempt to show how genuine this person is when speaking. But Takei, the man and the movie, embraces the repetition, the determination ÔÇö the hard-work of being the happy face of a changing, conflicted nation.