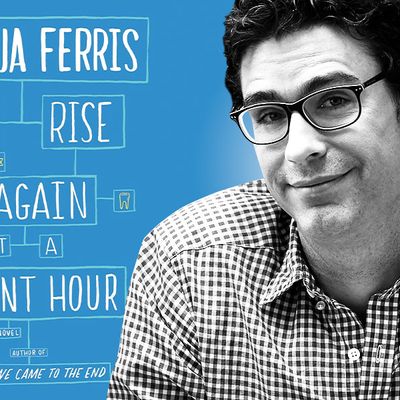

Last year, the Man Booker Prize ÔÇö the most prestigious book award in Britain and probably the world ÔÇö announced it would, for the first time, consider any book written in English and published in the U.K. On Tuesday, its judges made good on their threat; on their final ÔÇ£short listÔÇØ of six books are two Americans: Karen Jay Fowler (for We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves) and Joshua Ferris. To Rise Again at a Decent Hour, FerrisÔÇÖs third novel, is the often hilarious, often depressing existential howl of a New York dentist embroiled in a pseudo-ancient religion. We called Ferris up yesterday to talk about his new accolade.

Congratulations on making the short list. How are you?

Well, thanks. I should be good for the rest of the week.

And then what if you win?

Oh, yeah, that could last a month. But it was a surprise just to be long-listed. And then you start trying to figure out your odds with some inscrutable algorithm.

People do, famously, set odds for the Booker Prize.

IÔÇÖm now something thatÔÇÖs wagered on, which is usually the domain of horses and dogs. But I think itÔÇÖs totally cool. Though I think my odds are pretty bad. Well, I guess it depends on where you go. Some place I squeaked in at 5-to-1, at another itÔÇÖs 12-to-1.

What did you think when you heard the Booker would be accepting Americans?

I didnÔÇÖt know that it was such a good idea. WeÔÇÖve got a tremendous slate of prizes here in the U.S. already. But once I was long-listed, I thought, Well, now I get it! I think [expanding the prizeÔÇÖs scope] will only make the Man Booker even more mammoth of a prize, and inevitably smaller regional prizes will come in to fill any gap that the Booker will create. These things have a way of working out.

Why do you think the jury chose To Rise Again?

I donÔÇÖt know, itÔÇÖs a strange book. To be honest, I did not have a lot of confidence that too many people would go, Ah, the book IÔÇÖve been waiting for! ItÔÇÖs about a dentist whoÔÇÖs having a crisis, a Red Sox fan who hates Twitter. It just doesnÔÇÖt scream best-seller. I wasnÔÇÖt sure that it would strike anyone as compelling. I think the thing that it had going for it is itÔÇÖs funny and itÔÇÖs about a very contemporary moment with respect to technology.

Paul ÔÇö the dentist ÔÇö rails against the distractions of the internet, something lots of writers would understand.

ThereÔÇÖs a primal addiction that technology taps into that the human being is helpless before. ItÔÇÖs a kind of frenzy, and the eyes are just absolutely besotted with that lit screen, and it takes a willful and very conscious, very present effort to turn away from it.

ThereÔÇÖs also PaulÔÇÖs longing for cultural identity; he envies Jews for their minority status.

HeÔÇÖs a particularly lonely character. ThereÔÇÖs no legacy in his family, thereÔÇÖs no ritual, thereÔÇÖs no custom, no richness of inheritance. But I suppose that is to some extent, what do I want to say, the white manÔÇÖs burden? He neednÔÇÖt ever worry about his material comfort or the disadvantages of having anything other than shiny white skin. But these advantages also happen to impoverish him in many ways. HeÔÇÖs looking for something that makes life more colorful.

But I already have that. I consider among my friends Gary Shteyngart and Karen Russell and Rachel Kushner and Zachary Lazar. ItÔÇÖs a strong community of lots of people that have the same pathology.

WhatÔÇÖs the pathology?

Writing. My dentist doesnÔÇÖt have that. HeÔÇÖs inundated day in and day out with mouths. ThatÔÇÖs his community, and rotting mouths as a community only leads you to despair and death.

You have struggled, though, with expectations. Some critics who loved your debut, Then We Came to the End, were disappointed by your second novel, The Unnamed, and the reviews for this one were mixed. A New Republic review was initially headlined ÔÇ£Joshua FerrisÔÇÖs New Novel Ought to Destroy His Reputation.ÔÇØ Did you read that?

I didnÔÇÖt read it because I donÔÇÖt read reviews, but I did hear about it through various friends. And frenemies ÔÇö itÔÇÖs surprising how many of them there are. I suppose that to the world, the Man Booker Prize panel is going to be far more significant than a journalist who just doesnÔÇÖt like my book. Is it going to change anybodyÔÇÖs visceral reaction to the book? No. IÔÇÖve read many award-winning books that I thought were crap. But it does the nice thing of counterbalancing ÔÇö one might even say crushing ÔÇö what was as I understand it a fairly limited and unfair review. These are peopleÔÇÖs opinions, and if a group of people gets together and theyÔÇÖve been well vetted by the institution of the Man Booker Prize, I tend to take their opinion more seriously.

When did you stop reading reviews?

That was new for this book. Ultimately, it came to seem to me a form of ego that I preferred to live without. I would consume the good reviews like fast food, and they would become a crack high for a little while. Then it would fade quickly, and the bad reviews would just linger like a bad fart. So why go up and down when I can be on an even keel and actually get some work done.

Are awards different?

As long as IÔÇÖm not sitting around refreshing my page when the Pulitzer is announced, IÔÇÖm not wasting any time.

And what will you do with the $80,000 if you win the big award in London next month?

Fly back first class.