He couldn’t see past the walls at first, but then the wrought-iron gate swung open and the limo he was riding in pulled past the gate, and Michael Egan got his first view of the M&C estate.

The 12,600-square-foot Spanish Colonial, surrounded by immense columns and gaping bay windows, was previously owned by the rap mogul Suge Knight. Inside was a home theater and more than one aquarium. Outside he could see a Ferrari and Lamborghini, a tennis court, a swimming pool, and a hot tub big enough for a dozen people. To the neighbors, it might have seemed like just another Encino McMansion. To a 16-year-old from Nebraska, it seemed like everything he thought Hollywood would be.

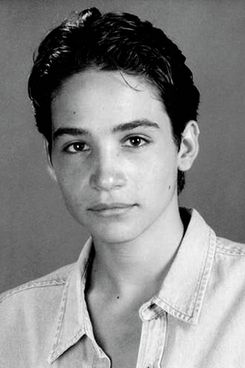

Egan was slim with dark hair, pale skin, and a bright smile. The son of divorced parents, he had been a popular kid who dreamed of being Tom Cruise. He’d attended his first model search when he was 12, an open call at a shopping mall in Omaha, which quickly led to a summer in New York, where he booked dozens of modeling jobs. When, a year later, his manager told his mother, Bonnie Mound, the next step was a move to L.A., neither of them needed convincing. Mound rented an apartment in the Valley and enrolled him in a school designed to accommodate the schedules of working actors.

It was one of his classmates there who, in June 1998, first brought him to the M&C estate, named for two of its occupants, Marc Collins-Rector and Chad Shackley. Those men, along with a third housemate, Brock Pierce, had recently been celebrated in the Los Angeles Times for creating a business that would make TV shows for the internet called Digital Entertainment Network, or DEN. They’d poached their president, David Neuman, from his job running Disney TV. David Geffen had showed interest in the company, socializing at the estate with other investors who, Egan was told, could be very helpful to him in his career. There was Garth Ancier, who at 28 had been the first programmer of Fox television and who would go on to high-level positions at NBC and the WB network. There was Gary Goddard, the director and Broadway producer. And there was the director Bryan Singer, who had just made his name with The Usual Suspects and was about to join the A-list with the X-Men film franchise.

What happened behind the walls of the M&C estate over the next two years is a matter of intense dispute. If you believe Michael Egan, he was groomed to submit to a life of abuse in what was essentially a pedophilic sex den. If you believe the men Egan accused—including Singer, who has been lying low since Egan filed a civil lawsuit against him in late April—he is a shakedown artist, contriving an abuse scandal, staging press conferences, and participating in an upcoming documentary, all in the hopes of a payout. Much of Hollywood has been watching Egan’s case unfold all summer, and not only for its lurid details. Was Egan just another Hollywood newcomer who traded sex for entrée into a business famous for allowing that very exchange, or is he the most public example of something more troubling: the industry’s rampant sexual abuse?

Egan is standing alone, awaiting my arrival at the baggage claim of McCarran airport in Las Vegas, the city where he’s lived since 2002. It’s a bright afternoon in June, two months since he held his explosive press conference at the Four Seasons on Wilshire Boulevard, tearful mother on one side, lawyer on the other. Now he’s in the middle of the backlash: denials, motions for dismissal, countersuits, anonymous attacks against his character, all of which just make him more eager to tell his story.

“June 23 will be two years of me not having a drink,” he tells me as we walk to his car. He is tan but rail-thin, and a certain jittery frailty comes through as he talks. His manner is like that of a lot of people in the early years of recovery—overcome by the relief they feel in talking at length about what they’ve been through. Quite often, Egan says, he still feels seized by emotions he can’t manage. “These people put so much fear in you when you’re a kid. But I still have fear. I had a dream last night that I was walking into a deposition and got shot.” He smiles and shakes his head. “That’s sick to think that stuff.”

As I spoke with Egan, both in person in Las Vegas and later over a steady stream of phone calls and emails and texts, his anguish became clear, even if the facts surrounding it remained stubbornly out of reach. Everything he says happened to him has been roundly denied, and every allegation lacks documentation. He was almost certainly taken advantage of (though by whom and to what extent has yet to be proved). It’s also true that he had his own motives for insinuating himself into the world of the M&C estate. Soon after he moved to L.A., he endured his first unsuccessful TV-pilot season. On the audition circuit, he ran into the same teenage boys, all as beautiful as he was, at every casting. What he needed were connections. The month he first visited the estate, DEN had premiered its debut program, Chad’s World. Practically no one watched the show, but the company payroll was staggering: $12 million in salaries with only one series in production.

After a few visits, DEN’s executives offered Egan $600 a week to do odd jobs around the estate. He said yes, and soon found himself embraced by the DEN family. He was given a starring role in a new DEN show called The Royal Standard, directed by Randall Kleiser, who had directed Grease and The Blue Lagoon; he was paid $1,000 more a week. He hung out at Independence Day producer Dean Devlin’s house and did screen tests for Roland Emmerich’s movie The Patriot and Freaks and Geeks. Along with the other teenagers he met through DEN, he was a regular at a place called Barfly, where he’d get so drunk he’d throw up. The estate, meanwhile, became famous for its parties, which were stocked with attractive young men. “I’ve spent some time at the Playboy mansion,” one person connected to DEN said later to the New York Post. “This place makes it look like a trailer.”

The grooming, according to the lawsuit, started almost on day one. Egan remembers being pulled aside by Collins-Rector, Pierce, and Shackley for hourlong one-on-one lectures about how they had gaydar and they knew that Egan really was gay (he says he is not). He remembers the ban on the wearing of clothes in the pool or hot-tub areas. And he remembers being locked inside a gun closet for resisting Collins-Rector’s advances. He also remembers the drugs—Valium, Vicodin, Xanax, Percocet, ecstasy, roofies. In the years to come, several other young men would come forward to talk about inappropriate behavior by the executives of DEN. There was a boy named Daniel who, according to a 2007 account of DEN’s rise and fall in Radar, wrote a suicide note that his brother intercepted before he could act on it: “I can’t go on. I let them use me as a sex tool. I let those assholes do all those terrible things to me. Good-bye.” There are several boys, including Egan, who would recall Collins-Rector aiming a gun at them and threatening to pull the trigger. And there was the boy who, in 2000, filed a lawsuit in New Jersey claiming Collins-Rector repeatedly sexually abused him from 1993 to 1996. Collins-Rector denied those allegations but then settled the suit shortly before leaving the company.

What made Egan’s accusations news this spring was that he didn’t just name DEN’s executives; he named prominent members of the gay Hollywood elite, including Singer. Egan’s lawsuit describes an incident in the estate’s pool when Egan was 17 years old. Collins-Rector allegedly passed Egan to Singer in the hot tub, where Egan “was made to sit on” Singer’s lap; Singer gave him a drink, mentioned finding him a movie role, told him he was sexy, and masturbated and fellated him. When Egan resisted, the complaint reads, Singer forced Egan’s “head underwater to make [Egan] perform oral sex upon him. When [Egan] pulled his head out of the water in order to breathe, [Singer] demanded that he continue, which [Egan] refused. [Singer] then forced [Egan] to continue performing oral sex upon him outside of the pool, and subsequently forcibly sodomized” him.

Egan says Singer’s behavior continued on trips the whole group took together to the Paul Mitchell estate in Hawaii. One night, the complaint alleges, Egan came across Singer in the pool area, whereupon Singer “put a handful of cocaine” under Egan’s nose, then “forced him to inhale it.” Singer entered the pool, where he “nonconsensually masturbated” Egan; pushed his head underwater and made him “orally copulate him”; and eventually brought Egan to his room, where “he again anally raped” him.

Singer’s official response to the accusations is that they’re fiction. “Bryan never acted inappropriately toward Mr. Egan,” says Singer’s lawyer, Marty Singer (no relation). “All of his claims are lies.” The lawyer’s statements have consistently addressed just the specific claims in the lawsuit, neither confirming nor denying that Singer and Egan had sex or knew each other; he did not return messages for this story.

On the many nights Egan remembers sleeping over at the M&C estate, he says his mother would call to make sure it was all right, and an adult would come to the phone and assure her all was well. And, in one respect, it was. Suddenly, things were happening for him career-wise. To walk away from M&C would mean telling himself he wasn’t cut out for Hollywood. When I ask Egan’s mother about that now, she bursts into tears. “We were raised in the Midwest, and we try to find the good in people,” Mound says. “And we went to New York and never had any problems, and he just seemed to be a success. He was just so happy and having so much fun.”

Over lunch, Egan comes back again and again to the notion of grooming—that a 16-year-old boy could be made to go along with almost anything, given the right motivation. “I was never a willing participant in what they did to me,” Egan says. “They ripped in and stole my soul. I became a robot. I had such fear instilled in me I was a nonfunctioning person. I may have become more of a compliant victim, but I was never willing.”

Egan didn’t choose the word compliant arbitrarily. The word is commonly used in abuse cases with teenage victims who, unlike toddlers or tweens, may have some degree of agency when interacting sexually with adults. These cases tend to follow a pattern: The abusers engage in a seduction process that normalizes the behavior until the victims go along with it—still victims, but also compliant participants. Legally, if the victim is under the age of consent, proving sexual abuse should be relatively straightforward, but that gray area of compliance often clouds the issue, making juries (and the public) less sympathetic to claims of abuse. Can you be exploited if you consent? What if you only say you were abused years later, after your career has dried up?

Sexual abuse in Hollywood has long been the subject of speculation. “It’s common enough that every boy child actor would have met a pedophile in their career at some point,” says Anne Henry, the mother of three child performers and co-founder of the BizParentz Foundation, a group for show-business families. Henry started BizParentz more than a decade ago to help families navigate the industry, but since then she has heard of hundreds of instances in which young actors say they’ve been harassed or abused.

Every few years, accusations surface in court, most of which fizzle with a plea. The accusers’ names are usually not public in these cases, and when actors like Corey Feldman do open up publicly, they don’t typically name their abusers. Egan’s case is one of the few where both the victim and the accused are publicly known, in part because victims have their own incentives for staying quiet. “When they were on the gravy train and they were the guy’s favorite, that was great for six months, two years,” says Kenneth Lanning, an FBI special agent of 30 years, now retired, who has investigated every variety of sexual-abuse case. “Then their careers fall apart. Now the guy’s finished with you and not returning your calls. Now you’re pissed.”

For nearly two years, Egan was making more money than he knew how to spend, going out to the Palm and taking trips on private jets, and, of course, being promised auditions. Then, one day, one promise didn’t pan out. “X-Men was a job that Bryan Singer said he was going to give me,” Egan says. When Egan’s DEN co-worker Alex Burton got a part, the role of a mutant named Pyro, and Egan didn’t, Egan says he was told it was because Burton was 18, a legal adult, and therefore able to work longer hours and with no supervision on set.

Then, the executives of DEN started pressuring Egan to become legally emancipated from his parents, which would allow him to work under adult work rules. His mother was offered stock in the company in exchange for permission; she declined. By then, it was 1999, and DEN was falling apart. Collins-Rector was facing his first lawsuit for alleged abuse, and DEN’s lawyer was asking everyone at the estate, including Egan, to sign nondisclosure agreements in exchange for stock. He didn’t sign. He still might not have walked away without the help of two other DEN employees. Alex Burton and Mark Ryan were both older than Egan and determined to call the police. Egan says they forced the issue one night at Egan’s house by telling his mother what had been happening. Bonnie Mound was shattered by the news. “I was still petrified,” Egan says, “but I started to get stronger once we were talking through it.”

Mound found the boys a lawyer, Daniel Cherin, who along with law enforcement encouraged the boys to collect more evidence. “So we went back and copied everything in the file cabinet,” Egan says. “We had photos of the drug bags and child pornography in different cabinets, and video of the gun closet they locked me in.” In early 2000, Egan was still sending emails to DEN’s executives, asking for money and even looking to hang out. The lawyers for Singer and the other defendants call this evidence of a shakedown; Egan says now it was part of the effort to collect evidence.

Egan’s great escape proved anticlimactic. The police and the FBI never charged anyone—Egan and his mother still aren’t sure why. “My mom heard from them once or twice, but that’s it. ” The three boys filed a civil lawsuit in 2000 for sexual abuse against Collins-Rector, Shackley, and Pierce. They did not name Singer, Ancier, Neuman, or Goddard. Egan’s lawyer, Cherin, told them he didn’t have enough evidence to connect the others to the abuse—at least not like he had on the three men who actually lived at the house. “The system doesn’t reward the he-said-she-said scenario,” Cherin tells me. He believed the high-profile targets had the resources to bury them in motions and counter-investigations. “I’m not a daredevil. I don’t get paid to take chances.”

While Egan, with his mother’s help, worked to litigate against the DEN executives, sitting for depositions and sifting through documents, the defendants fled the country without contesting the suit. The court awarded Egan and his fellow plaintiffs a $4.5 million default judgment, of which Egan says he collected just $25,000. The absence of consequences seemed to confirm everything Collins-Rector and the others had said: They were powerful enough to get away with it; no one would ever believe the boys; everyone who might help him would be too afraid of retribution to come forward. “I was pushed by my mom to talk to the government, to law enforcement. I was scared shitless,” he says. “To see that nothing happened—that if you ever did come out, that law enforcement never did anything, so who could you really trust—that was a hard thing for me to get over.”

He left Hollywood, and after a couple of years with his father in Nebraska, he moved to Las Vegas, working with his brother building theme parks. He married a woman he met there in 2005. But he couldn’t seem to put enough distance between him and what had happened at M&C. “I thought I could shove all these feelings down—‘I’m a big man, I can deal with this.’ But it was like dealing with a madman in your brain.” He was drinking hard, often alongside the only friend he’d made at DEN, fellow plaintiff Mark Ryan. In 2010, Ryan had an alcohol-withdrawal-induced stroke while trying to sober up; he never fully recovered and relies on a motorized wheelchair, barely able to communicate. “I have a friend who has basically lost his life,” Egan says. “Whenever I think I’m in a bad spot, I think Mark would trade places with me in a second.”

Egan kept drinking for two more years until 2012, when his wife left him. “I loaded my two dogs in my SUV and drove across the country while in withdrawal. I was having flashes in my eyes, I was sweating like a maniac.” Egan joined AA, attending 200 meetings in the first 90 days. Then he finally found another community to envelop him the way that DEN had—not just the recovery community, but the advocacy community for victims of sexual abuse.

In the spring of 2013, a year into Egan’s sobriety, his mother passed along a message from BizParents. A production company was planning a documentary about sexual abuse in Hollywood, and they wanted to interview Egan. The documentary is directed by Amy Berg, whose Oscar-nominated 2006 film Deliver Us From Evil examined an infamous California Catholic Church sex-abuse case. While Berg and her team won’t comment on the film or even reveal its title, she did tell one reporter in April that Egan will be in it. “It’s much bigger than anything about the one case,” she said. “It is a huge problem. It’s pervasive in Hollywood, and the time to explore it is now.” Egan, who’s seen it, says about a half-dozen other men like him are interviewed, none of whom he knew beforehand.

Egan suddenly felt like he was part of a movement. A producer with Berg’s documentary referred Egan to a sexual-abuse survivors’ group called the Let Go … Let Peace Come In Foundation, which was started by a sexual-abuse survivor named Peter Pelullo, who offered Egan more affirmation. “God knows how many children this has happened to from this situation in Hollywood,” Pelullo says. The foundation referred Egan to a trauma therapist, whom he still sees. Her most important message, Egan says, was that he wasn’t at fault. She explained to him how abusers groom their victims and wrangle compliance.

It was his experience with the survivors’ group that made Egan decide he needed to publicly accuse his abusers—all of them. Last fall, he and his mother went lawyer shopping. At least one prominent sexual-abuse litigator turned Egan down: “I believe every word he’s saying,” the lawyer told me. “But he’s dead on the statute of limitations.” California law allows for accusers age 26 and younger, or three years from the date they discover their trauma. Egan was 31 and had discovered his trauma as early as 2000, as his old lawsuit clearly demonstrated.

Then Egan found Jeffrey Herman, an ambitious lawyer out of Boca Raton who has won tens of millions of dollars in judgments against the Miami Catholic archdiocese and who has used the money to fund long-shot cases, most recently a failed set of claims against Kevin Clash, the voice of Sesame Street’s Elmo. Herman was once barred from practicing law for a year and a half for violating the Florida bar’s conflict-of-interest rules when he failed to disclose an investment that competed with a client’s business. But he seemed to be the sort of risk-taker Egan needed—a lawyer willing to take on a bumpy case if it meant opening up a new area of litigation.

I visited with Herman at his office in June a week or so before I met Egan. Tan and broad-shouldered, Herman said his investigators spent five months vetting Egan’s claims, turning up in the process an unpublished interview Egan gave to a reporter in 2001, in which he explicitly named Ancier, Goddard, Neuman, and Singer as his abusers. The interview helped convince Herman that Egan had a case. His staff also spoke with several men who’d been at the M&C estate. Some were too afraid to be named in the initial complaint, but Egan’s friend Mark Ryan, his father Fred tells me, was deposed from his wheelchair in Cincinnati and confirmed the abuse. Herman planned to get around the statute of limitations in California by filing a civil suit in Hawaii, which has a law allowing civil actions in abuse cases where the statute of limitations has expired. The trips to Hawaii, therefore, became the centerpiece of the suit.

Herman told me that he had been looking for a Hollywood case even before Egan came along. “I’m always looking for what the next church is going to be,” Herman said. “Where there’s power, there’s an abuse of power.” As star clients go, Herman said Egan was no more problematic than any other. “He’s lost in a way, because this is really horrific stuff. He’s fragile. Yet he’s sort of determined now.”

Herman was bracing himself for when, inevitably, the other side would dredge up the many contradictory statements Egan had said over the years and use them against him. “Mike’s story is very complex,” he said. “You’re going to have these inconsistencies, where his mind is disassociated from some of the abuse.” The most important thing Herman could do to bolster Egan’s case, he said, was to turn it into a beacon to draw in others. There’s strength in numbers. “The best way to get evidence is, I do a press conference,” he told me. “There’s always more victims.”

On April 17, Egan and Herman made their announcement at the Four Seasons, unveiling a lawsuit naming Singer, whose X-Men: Days of Future Past was about to score one of the biggest opening weekends on record. A few days later, Egan and Herman announced similar suits against Ancier, Goddard, and Neuman. “We’ve alleged that there’s a Hollywood sex ring, one of several sex rings,” Herman said. “The door is open now. If these investigations pan out, I will be filing many more cases.”

“The allegations against me are outrageous, vicious, and completely false,” Bryan Singer said in a statement a few days later, promising that “the facts will show this to be the sick, twisted shakedown it is.” Stories soon surfaced of Singer’s own parties, stocked, reportedly, with twinks his underlings thought he might like. Several published accounts, most quoting unnamed sources, described how Singer meets most of the younger men he dates through trusted friends who act as intermediaries—or, less charitably, procurers. Yet those who defended Singer painted a picture of the director as anything but predatory, saying he is powerful but cloistered, and, like many A-listers, dependent on friends to introduce him to new men, and that he is scrupulous about the age of his partners. Still others noted how prominent gay men are also often easy targets for these kinds of allegations, which feed into ugly homophobic stereotypes about gay men and pedophilia.

All four of the accused men said they’d never been to Hawaii with Egan, never raped him, never mistreated him. Bryan Singer’s lawyer Marty Singer pointed out that his client had never been approached or interviewed by the FBI back when Egan filed his first lawsuit, nor was he named in that lawsuit. He accused Herman of grandstanding, “using these lawsuits as an opportunity to promote himself and his law firm,” and added that his “reputation as an attorney leaves a lot to be desired,” noting the harsh wording of Herman’s suspension from the Florida bar for “engaging in misconduct involving fraud, deceit, and misrepresentation.”

Then came the counteroffensive: leaks to the media of emails from Egan to DEN asking for money. The media got hold of a deposition by Egan from the earlier litigation in which Egan said he’d never left the continental United States with anyone he was accusing of abuse. Now that the case hanged on the Hawaii trip, this statement was especially problematic. Herman, who claimed to have witnesses placing Singer in Hawaii with Egan, responded by saying he wasn’t “sure how [Egan] interpreted the ‘continental United States.’ ”

Herman soon found another client, a British national, a few years younger than Egan, who filed a similar complaint against Singer and Goddard. In response, Singer’s lawyer accused Herman of fabricating the substance of the new claim, and threatened to seek sanctions against him “for his reckless, unethical behavior.”

In late June, Egan went to a Goo Goo Dolls concert at the Red Rock Hotel and Casino, where, he says, a stranger cornered him in the restroom, blocking the exit for more than a minute. “He told me, ‘You need to go away! You need to go away! This is going to get intense!’ ” Then he served Egan with a civil suit filed by Garth Ancier, who was suing Egan, Herman, and his Hawaii co-counsel Mark Gallagher for malicious prosecution. The next day, Egan filed a police report for harassment.

Still, between the attention and the coming documentary, Egan felt unburdened for the first time in years: “I already think whatever happens with the case, whatever legal strategies we have to do, I feel already we’ve won.”

Just days later, Egan called me in a panic. His lawyer wanted him to settle with Singer, and Egan was appalled. “I would look like a complete liar if I came out and said the things he wants me to say!”

The details trickled out in the weeks that followed. Five more alleged victims of Singer’s had come forward to Herman, and at least some of them had accusations within the statute of limitations. Under the proposed settlement, those five accusers would split the lion’s share of the settlement, which one source close to the case says amounted to $20 million. Egan would get a mere $100,000.

The money bothered him, but the confidentiality demands of the settlement bothered him more. For Egan, being silenced by his own lawyer felt like a new betrayal. “I look at what Jeff did to me as no better than the pedophiles,” he said.

Egan refused to sign, and soon after, Herman dropped him as a client, applying to withdraw as counsel in all four of Egan’s lawsuits. Herman hired his own attorney to represent him in Ancier’s malicious prosecution lawsuit; he declined to comment any further for this story, and he has yet to send Egan the bulk of his case file. In late August, adrift without a lawyer or most of the documents from his own case, Egan temporarily pulled the plug on his lawsuits. The court dismissed his claim against Singer without prejudice, which would allow him to refile should he find a new lawyer. “Herman’s created such a mess for me that nobody wants to touch it,” Egan said during another anguished phone call. “In all honesty, based on what Herman’s done, I’m looking to sue Herman. I just think to myself, How does he put his head on the pillow at night knowing what he did to me?”

Egan has run into difficulties in bringing his case to the court of public opinion as well. The Amy Berg documentary, which he hoped would bolster his claims, has been slow to find distribution. While this fall’s DOC NYC festival has accepted the film, discussions with Mark Cuban’s Magnolia Pictures went nowhere. One source who’s seen the film says it’s emotionally powerful, with several shocking moments, but that the subject is too ripped-from-the-headlines for theaters, and perhaps better for TV or Netflix. Donna Daniels, a spokesperson for Amy Berg, says the filmmakers have “made the decision to self-distribute.”

What hurt Egan the most, perhaps, was that he’d ever thought this could have turned out any other way. He’d been warned by everyone, starting with three of his old DEN co-workers, whom Herman’s investigators had approached. “They told me, ‘Mike, we don’t want to get involved. You’ll never beat these people, they have too much power.’ I’ve tried to help the cause and all that. But I think, Man, I should have listened to them.”

There is just one sign that Egan isn’t merely shouting into the wind. In late August, an NYPD spokesman confirmed to BuzzFeed that this spring, a man in his 20s filed a forcible-sexual-assault criminal complaint against Singer for an incident he said took place in New York in March of last year. The complaint was filed just a few weeks after Egan went public, which could be an odd bit of vindication. “At the very beginning of all this,” Egan said the last time I spoke with him, “my mom said to me, ‘If you had the choice to take millions of dollars or see these people go to jail, what do you choose?’ And I said, ‘Send them to jail.’ ”

Not that he has high hopes that that will actually happen: No charges have been filed yet, and Marty Singer responded that his client “did not engage in any criminal or inappropriate behavior with anyone in New York or elsewhere.” Meanwhile, after briefly falling out of consideration, Bryan Singer is the top choice to direct the next X-Men movie.

*This article appears in the September 8, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.