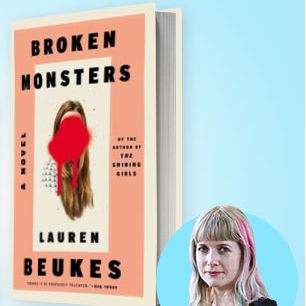

ÔÇ£The questions are the questions, Jeff. You know that,ÔÇØ South African novelist Lauren Beukes said to me, sitting at the Grey Dog Caf├® on Mulberry Street, right before we were supposed to do a gig at Housing Works Bookstore with critic/novelist Lev Grossman titled ÔÇ£WeÔÇÖre All Mad Here.ÔÇØ Her novel Broken Monsters, a great horror-thriller perfect for the Halloween season, had just been featured on the Today Show. SheÔÇÖd come from doing a radio interview and was expressing worry that AmazonÔÇÖs war with Hachette was going to eat into sales of a novel she thought was her best yet. As we began to talk, she was fielding TV and movie offers for Broken Monsters on her smartphone.

The questions might be the questions, but I was a little nervous about what I was asking this time around because Beukes started out as a journalist ÔÇö and a good journalist, too. The kind of journalist who deals in precise detail and who spent a lot of time, as she puts it, ÔÇ£Really developing an ear for how people speak and how they speak differently, and listening for that pull quote.ÔÇØ The dialogue in Broken Monsters is honed to the point that itÔÇÖs one of the novelÔÇÖs great delights. ItÔÇÖs a real achievement, even amid all the drama of a terrific horror-noir thriller with unique supernatural elements.

Broken Monsters chronicles the tense hunt for a unique killer: one whose victims are being fused with animal parts to create macabre yet strangely beautiful works of art. Homicide detective Gabriella Versado must try to solve these crimes, which may also be connected to graffiti drawings of odd doors that have begun to appear all over the city. Versado and her stormy relationship with her daughter stand at the novelÔÇÖs center, which is no surprise. Beukes has always been known for her idiosyncratic, three-dimensional female characters, and she often actively pushes back against ÔÇ£the way women are treated in noir, as very broken, fragile, femmes fatales.ÔÇØ Even better, Beukes achieves further depth by showing in crisp, sharp detail many different sides of Detroit, including the art community, the press, and ordinary citizens just trying to make a living in the shadow of atrocities.

What brought you to Detroit as a setting for the novel?

I was interested in Detroit because it is the go-to metaphor for the death of the American Dream. I have obviously seen all the beautiful, evocative photographs online of the abandoned places and [ruin-]porn aesthetic, and itÔÇÖs very beautiful and very haunting. But I know that there is a lot more to the city than that, and I wanted to dig deeper and get under the skin of it. Yes, there are abandoned buildings and, yes, it is a city thatÔÇÖs in terrible trouble. Bankruptcy, water cutoffs, all kinds of things. Poverty, crime, but at the same time, it is absolutely a vital, exciting place where people live and make a living and have ambitions and dreams and hopes.

You have a critique of ruin porn in the novel. What was your perception of people on the ground there, of this whole idea of their city being cast in this light? Of ruined buildings being seen almost as beautiful?

Most people donÔÇÖt like it. Interestingly, when I had cab drivers who were from just outside of Detroit, like Eight Mile or past Eight Mile, they would denigrate the city. They would go on about, ÔÇ£Yeah, look at this, the whole place is falling apart,ÔÇØ but the people who actually live there see it as problematic. They hated that people would just grandly dismiss the whole city based on a few abandoned buildings or a lot of abandoned buildings.

They hate the idea of [ruin-]porn tourists. They hate the idea of urban explorers coming in and glorifying the spoiling of the city. At the same time, I have photographer friends who hang out with urban explorers, and there is certainly a set of young artists who do that as well.  Some of them are very interesting, like the photographer Scott Hocking, who does installations in abandoned buildings. He kind of repurposes the space and makes them into different things. One roof installation he did, there were all these broken pillars, and he mounted broken TVs on top of the pillars and made it into a new Pantheon of the Gods. I really like art that is interrogating the spaces as well, and Scott gets a cameo in the novel.

You show the normal, everyday lives of people who are in Detroit, but you also have to have that ruin porn in the novel as atmosphere. How do you pull that off without descending into clich├® or contributing to that very thing?

I think itÔÇÖs interrogated throughout the novel by the characters. ItÔÇÖs a running theme, but at the same time, am I not going to have my showdown in an abandoned auto plant? Of course IÔÇÖm going to have my showdown in an abandoned auto plant, but thatÔÇÖs part of the subconscious of Detroit, and that plays into the allegory and the metaphor and the dream of Detroit. What it has been, what it is now, and what it might be again, so it was absolutely taking those clich├®s and just subverting the hell out of them, I hope.

ThereÔÇÖs another element in the novel, like an undercurrent, or just a hum or a beat. This idea of there being a world we donÔÇÖt see underneath our mundane world. ThatÔÇÖs really evocative to me of the things we donÔÇÖt notice.

There is definitely something strange happening in the novel, and there is a great unknown, whether that is the collective unconscious or the things that we see in cities that we donÔÇÖt notice. Especially if you look at it metaphorically: Our middle class lives where we are able to live happy existences without having to think about very basic stuff like where our gasoline comes from. There are always layers underneath. In this particular novel, those layers become quite uncanny, but it is about how we are haunted by our past. How we are haunted by previous iterations of the city and the people whoÔÇÖve been there.

There are different ways in which you approach that in Broken Monsters, in part because you are dealing with different social classes and different strata of society. Obviously that evokes certain novels, but it also evokes for me programs like The Wire.

When I set out to write it, I wanted to do The Wire meets Stephen King with a touch of Jennifer Egan. That was kind of what I was going for, so some nice social insight and beautiful sentences but also showing a wide range of the city and who the people are that live there. Showing how the city functions and how it fits together and doesnÔÇÖt fit together, where it comes apart. Then also just go kind of crazy, and really use the uncanny and supernatural elements as a way of breaking things wide open. I feel like using elements of the fantastical allows us to get a different perspective on things. ItÔÇÖs a way of exploding the metaphor.

Part of that, I think, comes from the sentences that you mentioned. There are some amazing sentences in there. But another thing that comes through is masterful dialogue ÔÇö and thatÔÇÖs reflective of strongly defined characters. For example, there is a homeless man who is more three-dimensional than any homeless person IÔÇÖve read before. Usually homeless people in novels tend to be, terribly enough, the throwaway characters, just there there to move the plot forward.

I interviewed a man called James Harris, who works at an organization called N.O.A.H. [Networking, Organizing & Advocating for the Homeless],┬áand I volunteered in the soup kitchen for a day there, and I spent a lot of time hanging out with him and just talking to him. A lot of my characterÔÇÖs biography is shared with James Harris. They are not the same person, but James gave me permission to use some of the things which happened to him when he was a kid, like being a landlord in ÔÇ£abandominiums,ÔÇØ which is his word.

Were there stereotypes that you wanted to avoid, that you were aware of either in the dialogue or in the descriptions of some of these people?

I was wary of killing the black guy, which is a horrible clich├®. I think it must be very frustrating for African-American actors to look at the script and flip through to see what page they die on.

IÔÇÖve read a lot of fiction on the noir/horror side, and itÔÇÖs very difficult for me to find something new in a novel of this type. Yet even the most horrible things you describe also have an element of unexpected beauty to them.

The novel was always about the artistic impulse. It was always about the urge to try and create something beautiful, to try and remake the world in a way where things are malleable, where things can reach their potential. As far as [the antagonist is] concerned, he is looking inside people to try and bring something beautiful out in them, and he just does it in a terrible way.

With The Shining Girls, I wanted to write a real serial killer, which is a loathsome, empty, broken human being. There is nothing admirable about them. They are just scumbags. Impotent scumbags. That is what real serial killers are. They are opportunistic, violent men, and they have no insight into why they do what they do, and they are certainly not outwitting detectives while sipping Chianti and saut├®ing someoneÔÇÖs liver. With this particular killer, I was much more interested in thwarted ambition. The creative urge, being possessed by the creative urge and trying to find your audience and not being overlooked. ItÔÇÖs kind of a broken masculinity as well. ItÔÇÖs a hungriness that the killer is filled with ÔǪ He doesnÔÇÖt mean for this to happen the way it does, and I feel a lot of sympathy for him. Which is not to say that the acts arenÔÇÖt atrocious and horrific and awful.

Jeff VanderMeerÔÇÖs latest novels form the Southern Reach trilogy: Annihilation, Authority, and Acceptance.