I have seen some pretty oddball acts of book flakkery in my tenure as literary critic. There was the Fifty Shades knockoff that arrived at my door packaged with lingerie and a lipstick-smudged note; the pitch letter that impugned the intellect of any reviewer who declined to cover the book in question; the loon who implored me, weekly, to join her in discussing her novel in her private chateau in France; the book trailer for Nelson DeMilleÔÇÖs Wild Fire.

But all of these, and many more, were handily trumped in brazenness and bad taste by Governor Andrew CuomoÔÇÖs impromptu act of book promotion yesterday. At a press conference about New York and New JerseyÔÇÖs poorly conceived, poorly executed, much-criticized Ebola quarantine policy, the governor veered weirdly off-message ÔÇö or on it, from that all-consuming perspective of, you know, the ego. ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm asking those people who were in contact with infected people: Stay at home for 21 days. We will pay,ÔÇØ the governor said. ÔÇ£Enjoy your family, enjoy your friends, read a book, read my book.ÔÇØ

Oh, my. Farewell, desert-island book; hello, Ebola-quarantine book. This critic strongly recommends against finding yourself alone with nothing to read but a second-rate, self-congratulatory political memoir by a tone-deaf (QED) governor. Herewith, then, some better reading material to take with you to a global pandemic, or to an unheated tent in New Jersey, or on that flight you just booked to a saner state.

Best current coverage of Ebola: Read Maryn McKenna (of Wired, National Geographic, Scientific American, and elsewhere), whose work is rigorously factual, wonderfully written, appropriately scary, and consistently sane. For a broader perspective on pandemics past and pending, you can also check out her terrific books on drug-resistant staph and on the Epidemic Intelligence Service. (Yes, thatÔÇÖs a real branch of the U.S. government.)

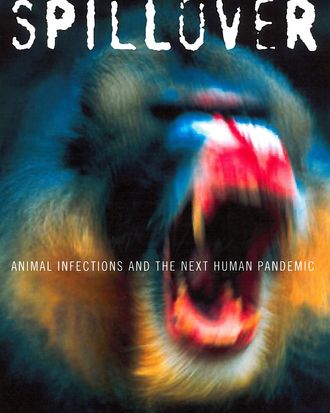

Best nonfiction book about pandemics: Science-writer extraordinaire David QuammenÔÇÖs Spillover, which takes on the subject of zoonotic diseases ÔÇö those that, like Ebola, jump the barrier from wild animals to humans. You will learn a ton, you will have interesting new nightmares, and you will rethink any fondness you might have once had for bats.

The nonfiction book about Ebola you shouldnÔÇÖt read: Robert PrestonÔÇÖs 1994 The Hot Zone: much hyped, very fun, and ÔÇö to paraphrase the subtitle ÔÇö terrifyingly untrue. Instead, read this concise critique by blogger and infectious-disease epidemiologist Tara Smith ÔÇö who, like McKenna, is doing a terrific job of covering the current Ebola situation.

The original plague book (okay, not counting the Bible): Giovanni BoccaccioÔÇÖs The Decameron. The setup: Seven women and three men, fleeing the bubonic plague, hole up in a villa outside Florence, where, to pass the time, they tell each other a hundred tales. (Hence the title.) Forget whatever preconceptions you may have about 15th-century literature; these stories are bawdy, funny, moving, and just generally excellent to read.

Best use of epidemic as extended metaphor: LetÔÇÖs call it a draw between Albert CamusÔÇÖs The Plague and Jose SaramagoÔÇÖs Blindness. The latter, about contagious loss of vision in an unnamed city, is the among the creepiest, saddest books IÔÇÖve ever read about what afflicts us and how we afflict one another. The former is a specific, convincing novel about contagious disease, in which matters progress very quickly from rats dying in the streets to people imposing martial law, attempting to flee, claiming God has called down punishment on the heads of the wicked, and generally behaving as humans do in the face of fear. But it is also a great novel about the human condition ÔÇö about the problem of how to live freely when faced (as, sorry, we all are) with certain death.

Best pair of epidemic novels (sort of) by a single author: Daniel DefoeÔÇÖs Robinson Crusoe is, in a sense, the ultimate quarantine novel, while his Journal of the Plague Year turns from the terror of being alone on an island to the terror of living and dying in a crowd ÔÇö specifically, in London, in 1665, when the black plague killed some 100,000 people.

Best epidemiological detective story: Steven JohnsonÔÇÖs The Ghost Map, a lovely, literary book about cities, sickness, science, and the 1854 cholera epidemic that changed how we understand and respond to contagious diseases.

Best literature about AIDS: Among epidemics, AIDS has claimed the most attention in recent history (although, in the United States, not the most lives: That would be the flu). Likewise, it has inspired the most books. For a start, read Randy ShiltsÔÇÖs imperfect but everything-altering And the Band Played On; Tony KushnerÔÇÖs Angels in America (itÔÇÖs as wonderful to read as to watch); and the late South African writer Phaswane MpeÔÇÖs Welcome to Our Hillbrow, a kind of eulogy-as-social-commentary set in a poor, immigrant-heavy neighborhood of Johannesburg and addressed by an anonymous narrator to a man who commits suicide before he can die of AIDS.

Best childrenÔÇÖs book about the bubonic plague: Marguerite de AngeliÔÇÖs The Door in the Wall, a 1949 Newbery Medal winner about a little boy in the Middle Ages who dreams of becoming a knight but loses the use of his legs. Full disclosure: I havenÔÇÖt read it in, oh, a quarter of a century. But as a kid, I adored it.

Best title for a book about infectious disease: Kate MarsdenÔÇÖs On Sledge and Horseback to Outcast Siberian Lepers. The journals of an intrepid Victorian woman who traveled to leper colonies in the 1890s. Also, the unfrozen caveman lawyer of book titles.

Worst book-critic confession: yes, I know there are countless science-fiction books about epidemics, but IÔÇÖm poorly read in that particular micro-genre and thus ill equipped to identify the good ones. But by all means, have at it in the comments section.