Selma director Ava DuVernay’s father, Murray, didn’t join Martin Luther King Jr. during his five-day Freedom March from Selma to Montgomery in 1965, but he wasn’t far away, watching the protesters pass by his family’s farm in Lowndes County, Alabama, located smack-dab between the two cities. “He’s from the backwoods, where Klan snipers were hiding in the trees trying to pick off marchers,” says DuVernay, who’s widely expected to make some history of her own, with Selma, by becoming the first black woman to earn an Oscar nomination for Best Director. These days, her father drives a mail truck in Montgomery, says DuVernay, and one fine morning this past June, he got off his shift, headed downtown, and saw “his daughter shut down the streets of the capital of the state of Alabama so she could shoot a movie about Dr. King.”

DuVernay, 42, didn’t just close streets for the triumphal final scene of Selma, the riveting civil-rights drama she also co-wrote, which chronicles three pivotal months that led to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. She took over the marble steps of Montgomery’s state capitol building, the very ones that Governor George Wallace had tried to prevent King (played in Selma by David Oyelowo) from setting foot on when he made his march-capping speech. “Now I had taken over that building,” says the filmmaker, “and my dad was standing there with a tear in his eye. That may be one of the greatest moments of my life.”

Getting to that moment was a long, unlikely journey. To again point out the obvious, DuVernay is a black woman, and there aren’t many people like her directing movies of any budget these days, let alone a $20 million studio tentpole about a historical icon that’s opening on Christmas Day. By comparison, her last movie, 2012’s Middle of Nowhere, was an intimate look at the life of a woman waiting for her husband to get out of prison. It cost $200,000. This hundredfold leap is daunting stuff, but it hardly shows. The first time I meet DuVernay, she plops down next to me and starts gabbing in her great raspy voice like we’re old friends. We’re at a decadent Paramount-hosted dinner, the existence of which indicates the studio is betting big on the movie. This isn’t even a premiere; it’s a celebration of the first look at five minutes’ worth of semi-finished scenes at New York’s Urbanworld Film Festival.

DuVernay is so charming and chatty that we’re about 12 shoulder squeezes and knee slaps deep before I realize she has no idea I’m writing about her. She’s fully clued in three weeks later, when she picks me up in her car during a momentary escape from the Selma editing bay. We’re off to get vegan soul food in Inglewood, the historically black neighborhood in South Central L.A. that was her old stomping ground. (DuVernay grew up in Lynwood, next to Compton. Her parents and four younger siblings moved to Montgomery after she finished high school.) She majored in African-American studies at UCLA, and the dreadlocked DuVernay doesn’t seem far removed from those college days, looking every bit the urban intellectual in her black-framed glasses, floor-length cotton dress, army-green jean jacket, and sandals. “I came here every weekend for eight years,” she says as we cruise down Crenshaw Boulevard. “The closest I can describe it for non-black people from the hood would be American Graffiti,” she says. “Kids in cars, black and brown people, looking at each other and having a good time.” Back in the day, she says, they’d call it the ’Shaw: “‘You going to the ’Shaw this Sunday?’ ‘Yeah, we rollin’.’”

Our route takes us into the hills of View Park and Leimert Park, bastions of L.A.’s African-American upper and middle classes. DuVernay tried unsuccessfully to buy one of the glorious Spanish Colonial homes here. “Listings don’t come up in traditional sources,” she says. “It’s all like, ‘Miss Johnson is in the hospital,’ and you’ll be like, ‘Woo, her house is coming up.’ It’s very inside, and I wasn’t inside.” So she moved to Beachwood Canyon and spent $50,000 she’d saved for a down payment on her 2010 feature debut, I Will Follow. “I bought a career instead of a house,” she says.

“I never had a desire to be a filmmaker,” DuVernay tells me. “As a child and a teenager and in college, I was not aware of black women making films.” But she loved movies and wanted to be around them, so after UCLA she worked as a publicist at 20th Century Fox, then started her own marketing firm at 27. Her DVA Media + Marketing specialized in delivering audiences of color to films like Dreamgirls and Invictus. She was even hired as a consulting publicist on Selma years ago when Lee Daniels was attached as the director and the U.K. producer, Pathé, needed help facilitating communications with the King estate. “I remember getting a call from some British people asking if I would work with this film,” says DuVernay. “I wasn’t even directing at that time.”

It was while working as a unit publicist on Michael Mann’s 2004 L.A. neo-noir Collateral that DuVernay felt the urge to tell her own stories. She made a short film, 2006’s Saturday Night Life, about a day in the life of a single mother, and followed that with 2008’s This Is the Life, about the Leimert Park café where she used to rap as part of the duo Figures of Speech, and 2010’s My Mic Sounds Nice: The Truth About Women in Hip Hop for BET, all while running her marketing company. She had an idea, inspired by “a homegirl of mine,” she says, that would become Middle of Nowhere. But she couldn’t get funding, so she did the more modest I Will Follow, based on DuVernay’s experience packing up the house of an aunt who had died of cancer. Roger Ebert was an early champion, calling it “the kind of film black filmmakers are rarely able to get made.”

DuVernay says she remembers during the I Will Follow shoot “thinking what a waste it had been to be on spin 12 years as a publicist.” But eventually she realized that her years as a flack weren’t a hindrance. She was organized and knew how to prioritize, communicate with actors, and articulate her vision, “the skills one uses as a publicist,” she says. She also knew the business and co-founded the African-American Film Festival Releasing Movement, which aims to get black cinema into movie houses. AAFRM initially released I Will Follow to five theaters, and the film earned back three times its budget. Still, DuVernay kept her day job, at least for a while. The Help (2011) was the last movie for which she did publicity before putting her company on hold to make Middle of Nowhere.

She became the first African-American woman to win Best Director at Sundance for that movie. Yet the win, she says, “raised my profile from zero to 2.2, maybe.” Prada commissioned her to do a branded short starring Gabrielle Union, and for ESPN she made Venus Vs., about Compton native Venus Williams’s fight for gender pay equality in professional tennis. “They were the only two,” says DuVernay. “It wasn’t a clamor from Hollywood at all.”

David Oyelowo likes to tell the story of how, when he first read a Selma script in July 2007, “God told me I would play the part of Martin Luther King.” Unfortunately for him, “the director at the time didn’t agree with God.” That director was Stephen Frears. He, Paul Haggis, Michael Mann, Spike Lee, and Lee Daniels were all reportedly attached before DuVernay. (Steven Spielberg is also working on his own King biopic.) When I ask Oyelowo if he believes DuVernay was divinely ordained to direct this movie, he says, “I have absolutely no doubt in my mind.”

As evidence, he points to “the bizarreness of how I met Ava.” During a 2010 round of fund-raising for Middle of Nowhere, DuVernay’s producing partner reached out to a Canadian friend, who reached out to his Canadian friends, one of whom sat next to Oyelowo on a flight to Vancouver. They struck up a conversation. “David takes the script from a stranger and ends up calling me,” says DuVernay. “He says, ‘My name is David Oyelowo, you may not know me. But I’m an actor. I really loved this script, and I’d love to talk to you about it.’ ” Oyelowo eventually played the part of the bus driver who gives the film’s protagonist a shot at new love.

Meanwhile, Daniels had taken over Selma and cast Oyelowo as King. But then he pulled out after making 2013’s Lee Daniels’ The Butler, feeling he’d made his civil-rights movie. Determined not to let the project wither, Oyelowo floated DuVernay’s name to the producers: “I said, ‘Look, I’ve just worked with this director who is amazing with human stories.’ I felt that to portray Dr. King, you needed to humanize him.”

Oyelowo knew there’d be pushback from the producers because DuVernay hadn’t handled a large production before. “But as I was gaining traction,” he explains, “I let her know, ‘I’m having a conversation right now. I hope this is something you’re actually amenable to.’” Then she told him that her father is from Lowndes County. “I didn’t have to learn Selma to make Selma,” DuVernay says. “I didn’t have to research what kind of place this is. The people I love most in the world live in that part of the country.”

Even after she was offered Selma, she needed convincing. “I wasn’t interested in making a Mississippi Burning through the eyes of a white protagonist,” she says. The film’s original script was by Paul Webb, a white Englishman, and focused more on LBJ’s backroom political efforts to pass the Voting Rights Act. Webb’s effort had landed on the Black List of best unproduced screenplays all the way back in 2007. But DuVernay said she’d take the film only if she could do a rewrite. The producers agreed, and she got the job in March 2013.

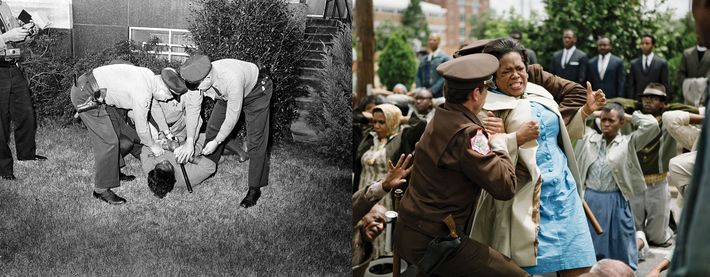

“My interest was showing people on the ground in Selma,” says DuVernay. “The band of brothers and sisters who were around King.” She wrote new scenes about the battle for control between King’s Southern Christian Leadership Committee and the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, as well as ones highlighting the leaders’ savvy strategy of creating dramatic, newsworthy images. “Someone standing up against a trooper with their hands behind their back,” explains DuVernay, “is a more sympathetic image than someone with a rock in their hand.” Her script has at least two dozen new or newly fleshed out characters, including SNCC co-founder Diane Nash (Tessa Thompson), the gay SCLC leader Bayard Rustin (Ruben Santiago-Hudson), and Coretta Scott King (Carmen Ejogo).

The biggest change, of course, was making King central to the narrative. The challenge was doing it without citing his speeches — his estate didn’t grant permission to use his words. “It was worth taking creative license with King’s speeches in order to get the film made,” DuVernay says. “If you sit there waiting for the rights, another 50 years are going to go past.”

The script won’t have DuVernay’s name on it though. “There was a contract in place before I was a twinkle in anybody’s eye that Paul Webb had the prerogative to retain credit,” she says. “And that’s where we are. The film is in the world and doing what I wanted it to do. I wish him well.” (Through a representative, Webb declined to comment for this piece.)

For his part, Oyelowo says, “I found myself looking at that original script thinking, How am I going to imbue this with complexity? In Ava’s hands, I found myself going, How am I going to rise to the occasion?” He so deeply embodied King in his performance that DuVernay says some cast members didn’t know he was British. “I had to get to the place,” says Oyelowo, “where I was emanating who he was.”

Also rising to the occasion was Oprah Winfrey. She came on as a producer at the request of Oyelowo, who’d played her son in The Butler. “Oprah carried us over the finish line,” DuVernay says. “She blocked and tackled for me.” DuVernay also persuaded Winfrey to play the part of Annie Lee Cooper, a woman subjected to unfair literacy exams when she tries to register to vote. Her first scene in the movie was on the day Maya Angelou died. “I said, ‘Let’s reschedule,’ ” recalls DuVernay. “She said, ‘No, I’m going to do this for her.’ ”

Freedom Fighters John Lewis and Andrew Young, who appear as characters in the film, were frequently on set. One marcher, still bearing scars from when one of Wallace’s goons assaulted him, was also an extra in the film. “You can’t honor somebody’s story,” says cinematographer Bradford Young, “and not let them be part of the process.” Perhaps the production’s hardest day involved creating the brutal, frenetic “Bloody Sunday” sequence, when protesters are rushed by whip-cracking state police. On the day of shooting, rain stoppages kept ruining scene continuity, and there weren’t enough people to fill out the mayhem. But DuVernay kept cool. “Logistically, I likened staging ‘Bloody Sunday’ to managing a red carpet at the Mann’s Chinese and shutting down Hollywood Boulevard,” she says. “You’re organizing a lot of activity around one focal point. At a red carpet, it’s when Charlize Theron gets out of the car; on Selma, it’s David as King.”

When I left DuVernay in mid-October, she was overseeing a Los Angeles sound studio trying to relocate a little girl’s laugh she knew had gone missing from Selma’s opening scene, which cuts between King receiving the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize and four doomed Alabama black girls in their Sunday best tromping down the steps of Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church on September 15, 1963. “There’s a giggle on the stairs that’s not on the track,” DuVernay told her engineers — and it was essential, she insisted, that we hear that bright burst of joy and life before a Ku Klux Klan–planted bomb rips through the building.

The first audience to witness that explosion was at L.A.’s AFI Fest in early November. DuVernay arrived having been up for 37 hours straight, working on postproduction with her longtime editor, Spencer Averick. They were both feeling loopy and emotionally raw. “We almost threw in the towel,” says Averick. “It felt like, Okay, this is not going to work out.” DuVernay was so ragged that she didn’t notice that people were clapping and crying during the screening. “I was floating through the whole thing,” she says. “They were wheeling me around like Bernie in Weekend at Bernie’s.”

She was able to pay better attention later that month, when Selma earned another standing ovation at its first full New York airing. The film is now firmly established as an Oscar front-runner. I saw DuVernay there looking (slightly) well rested in a long striped skirt and pink cashmere sweater. Despite the acclaim, the work wasn’t done. Jazz musician Jason Moran was putting the final touches on the score, and she’d be tweaking till her deadline, four days away. “It’s like a sculpture that everyone wants, but the edge is not rounded yet,” she said about Selma. “‘Just give me two seconds to get that part done!’ That’s how I feel.”

DuVernay was up against the clock, but in a far more profound way, her timing is right on. The afternoon of the New York screening, Missouri governor Jay Nixon declared a state of emergency, allowing him to have the National Guard intervene in anticipated protests in reaction to the Ferguson grand-jury decision. It was hard not to think of Selma, 1965. “The current dismantling of the Voting Rights Act and the breaking of the black body at the hands of police, this is not new,” DuVernay pointed out.

Selma resonates keenly now, but DuVernay knows its existence is a little lucky. She could be stuck in developing or financing. She could still be working PR on someone else’s movie. “For a film to be made is a small miracle,” she said. “And sometimes it’s a large one.”

*This is an extended version of an article that appears in the December 1, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.