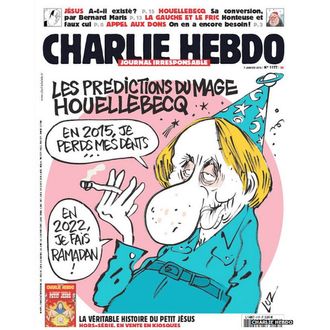

If gunmen hadnÔÇÖt attacked the offices of┬áCharlie Hebdo┬átoday, killing 12 people (including the provocative magazineÔÇÖs editor-in-chief), the conflict over IslamÔÇÖs┬áplace┬áin Europe would still have been ParisÔÇÖs topic one. There were yesterdayÔÇÖs rallies in Germany┬áto talk about, some in sympathy with FranceÔÇÖs anti-immigrant National Front, but also┬áthe┬ápublication of the sixth novel by┬ánotorious┬áanti-Muslim provocateur Michel Houellebecq, out today. A caricature of┬áHouellebecq┬ágraces┬áCharlie HebdoÔÇÖs┬ánew cover, after all.

ÔÇ£The predictions of the sorcerer Houellebecq,ÔÇØ reads the headline, beside an unflattering drawing of the author smoking in a magicianÔÇÖs outfit. ÔÇ£In 2015, I lose my teeth,ÔÇØ reads one speech bubble. ÔÇ£In 2022, I observe Ramadan.ÔÇØ The novel in question,┬áSoumission (Submission), has a plot even more tendentious than those of Houellebecq past. In 2022, the National FrontÔÇÖs Marine Le Pen runs for prime minister against a purportedly moderate Muslim candidate; French leftists side with the latter. The next day, Sharia law, more or less. The narrator, already recanting his atheism, picks up Islam (enticed by the polygamy). The rest of Europe follows, it seems, fashioning a caliphate in the image of the Roman Empire.

No one yet knows (though many have speculated) whether the publication of┬áSoumission┬áhad anything to do with the attack, but the author and Islam have a┬álong┬áhistory. ÔÇ£The stupidest of all religions,ÔÇØ he┬áonce┬ácalled it in an interview ÔÇö a quote that got him charged in 2002 with inciting religious hatred (though a Paris court later dropped the charge).

France has a long love-hate relationship with Houellebecq, who seems to rate┬álibert├®┬áabove┬áegalit├®┬á(and ignore┬áfraternit├®┬ácompletely). The novel that precipitated his incendiary interviews was 2001ÔÇÖs┬áPlatform, wherein a narrator finds blissful escape in Thai sex trafficking before a terrorist massacre ends the reverie. Like other of his novels (and like┬áCharlie Hebdo), it rode the French fault line between religious tolerance and cultural pride ÔÇö not only in the nationalistic sense but in a bedrock secularism that led to the banning of the burqa. Houellebecq was too talented a novelist to dismiss and too impulsively contrarian to pigeonhole. He was also, at least in France, too famous to ignore ÔÇö Norman Mailer with a curmudgeonly dash of Jonathan Franzen and the occasional pinch of Ann Coulter. There was always, for the French, something to love and something to hate. In 2010, he was finally awarded the prestigious Prix Goncourt for the relatively tame┬áThe Map and the Territory. That said, he was also accused of plagiarizing from Wikipedia, and the novel did contain a miserable character named Michel Houellebecq, who was brutally murdered.

Soumission┬áleaked extensively online in recent days, and Houellebecq has already peppered French media with interviews. He made many of the same talking points in a long (and rather hostile)┬áEnglish-language┬áexclusive with┬áThe Paris Review┬áthis week, answering the interviewerÔÇÖs accusations that he was stoking shallow controversy and scaremongering. ÔÇ£Yes, perhaps,ÔÇØ he said. ÔÇ£Yes, the book has a scary side. I use scare tactics.ÔÇØ He admitted his scenario wasnÔÇÖt very realistic, but envisioned a more gradual Islamist takeover.┬áAs it happens, the threat of a takeover like that is the subject of another book, by another novelist-provocateur, Eric Zemmour ÔÇö this one a work of polemic nonfiction about the decline of traditional European values that has been on the best-seller lists for months. ItÔÇÖs called┬áThe French Suicide.

Unlike Zemmour,┬áHouellebecq┬áisnÔÇÖt┬áa big fan of the West, either. ÔÇ£Look, the Enlightenment is dead, may it rest in peace,ÔÇØ he said, announcing that heÔÇÖd also forsaken atheism and was now an agnostic. The whole world yearns for religion, he said, and Islam might not even be such a bad thing. If youÔÇÖre a man, anyway.

ThatÔÇÖs the weirdest thing about HouellebecqÔÇÖs novel ÔÇö and what┬áCharlie Hebdo┬áwas getting at with its caricature. With┬áSoumission, heÔÇÖs out-contrarianed the contrarians. In his imagined battle of civilizations, he might side with Islam. As he told Sylvain Bourneau in┬áThe Paris Review, ÔÇ£the Koran turns out to be much better than I thought ÔǪ The most obvious conclusion is that the jihadists are bad Muslims. Obviously, as with all religious texts, there is room for interpretation, but an honest reading will conclude that a holy war of aggression is not generally sanctioned, prayer alone is valid. So you might say IÔÇÖve changed my opinion. ThatÔÇÖs why I donÔÇÖt feel that IÔÇÖm writing out of fear. I feel, rather, that we can make arrangements.ÔÇØ

Is he joking? ItÔÇÖs entirely possible. So was┬áCharlie Hebdo┬áwhen it ran an issue ÔÇ£editedÔÇØ by the prophet Muhammad, promising ÔÇ£100 lashes if you donÔÇÖt die of laughter.ÔÇØ Neither the National Front nor jihadists are known for their sense of humor. HoullebecqÔÇÖs publisher, Flammarion, was evacuated today, and Houllebecq was placed under police protection.