With historyÔÇÖs biggest, most profitable story about a superhero team ÔÇö the inevitable megasmash Avengers: Age of Ultron ÔÇö coming out this week, letÔÇÖs take a moment to think about what makes such teams work as fictional constructs. Why do comics readers and moviegoers come back to this simple, stupid idea (a bunch of people with miraculous abilities fight things and hang out together) over and over again? Sure, part of it is simple bigger-is-better maximalism, but we donÔÇÖt crave superhero teams simply because more fists mean more punching. Ever since the first major superteam debuted in 1940, the concept has evolved into something that ÔÇö when itÔÇÖs done well ÔÇö is unlike any other kind of fictional grouping.

Much as superheroes can express an individual struggle writ large, the most interesting superteam stories use extreme violence, anguish, and triumph to dig into group dynamics. ItÔÇÖs been a gradual evolution, but if we look at 12 iconic superhero-team lineups (well, technically, 14, but weÔÇÖll get into that) that have changed the history of superhero fiction, we can get a better understanding of why a story like The Avengers or the eventual Justice League films grab attention more than a movie about any single member of those groups.

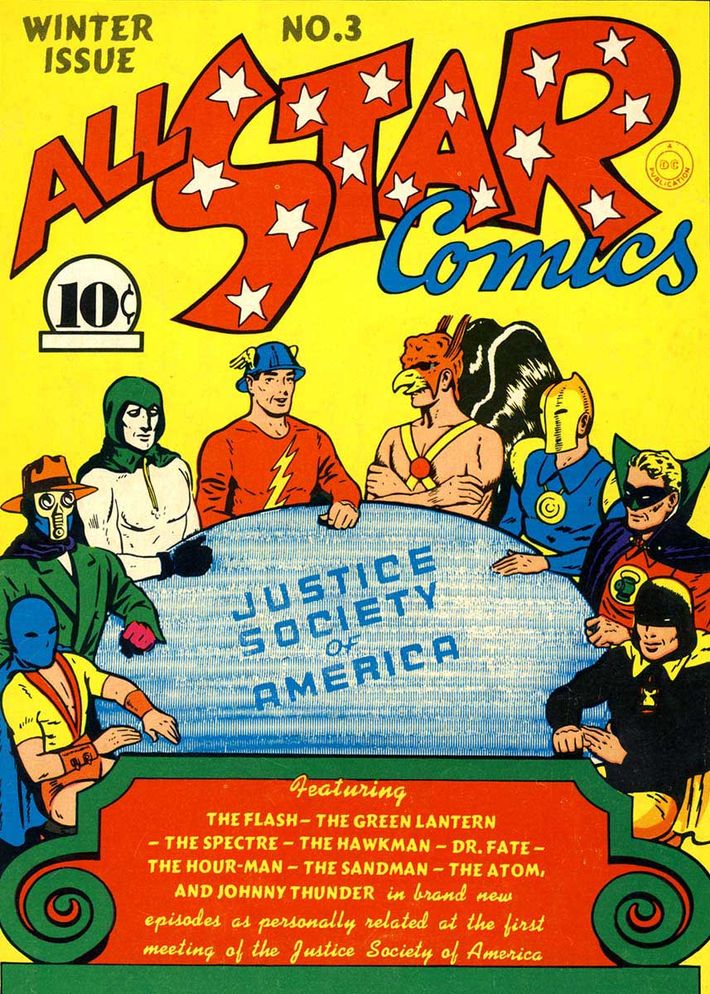

1940: Justice Society of America

To be honest, the Justice Society mostly only matters in the history of superhero teams because they were the first. In 1940 ÔÇö just two years after Action Comics No. 1 had launched the idea of the superhero and kicked off a publishing race to crank out heroes at a feverish pace ÔÇö two publishers threw eight of their superpeople together for some adventures. (ItÔÇÖs not worth getting into the intellectual-property-wrangling here, but suffice it to say that the Justice Society soon became owned by the company we now know as DC Comics.) The early Justice Society stories ÔÇö largely written by Gardner Fox ÔÇö arenÔÇÖt really worth rereading. The plots are repetitive, their exploits were explicitly misogynist (in that Wonder Woman joined and was instantly relegated to the status of team secretary), and Batman and Superman were never full-fledged members. But the Justice Society introduced the notion of characters with remarkable abilities joining forces in a formal organization, as well as other lasting tropes: a rival team of supervillains (in this case, the Injustice Society) and flux in membership (characters often left once they were popular enough to merit their own solo series). The superhero genre would never be the same.

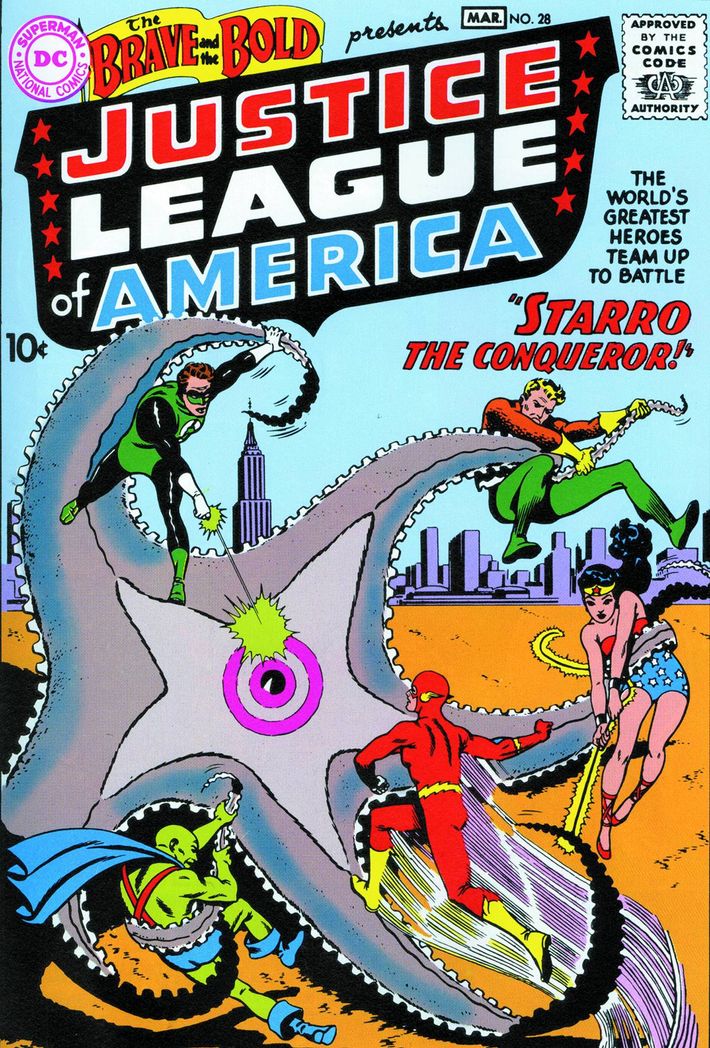

1960: Justice League of America

The Justice Society may have been the first superteam, but the Justice League are the longest-running ÔÇö and their original membership lineup has become the most iconic and imitated grouping in superhero history. Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, Green Lantern, Flash, Martian Manhunter, Aquaman: These became the archetypes upon which countless adaptations, parodies, knockoffs, and homages (one of which weÔÇÖll address on this list) were based. That lineup has undergone constant changes ever since, the team has splintered and subdivided over and over, and even in the early issues (written by an aging Gardner Fox), Batman and Superman were hardly ever around ÔÇö but there was something ineffable about those seven characters. Why? I defer to one of the greatest superhero-comics writers of all time, Grant Morrison, who wrote the teamÔÇÖs stories in the late 1990s. He was fond of saying the Justice League were rough analogues of the Greco-Roman pantheon (minus the weird sex stuff): Superman was Zeus, Batman was Hades, Wonder Woman was Athena, Flash was Hermes, and so on. (He also sometimes compared them to the United Nations, in that they seem to exist above any particular ideology or nation despite their original name.) Between them, there was simply nothing they couldnÔÇÖt do. When it comes to power fantasies, you canÔÇÖt get much more powerful than this.

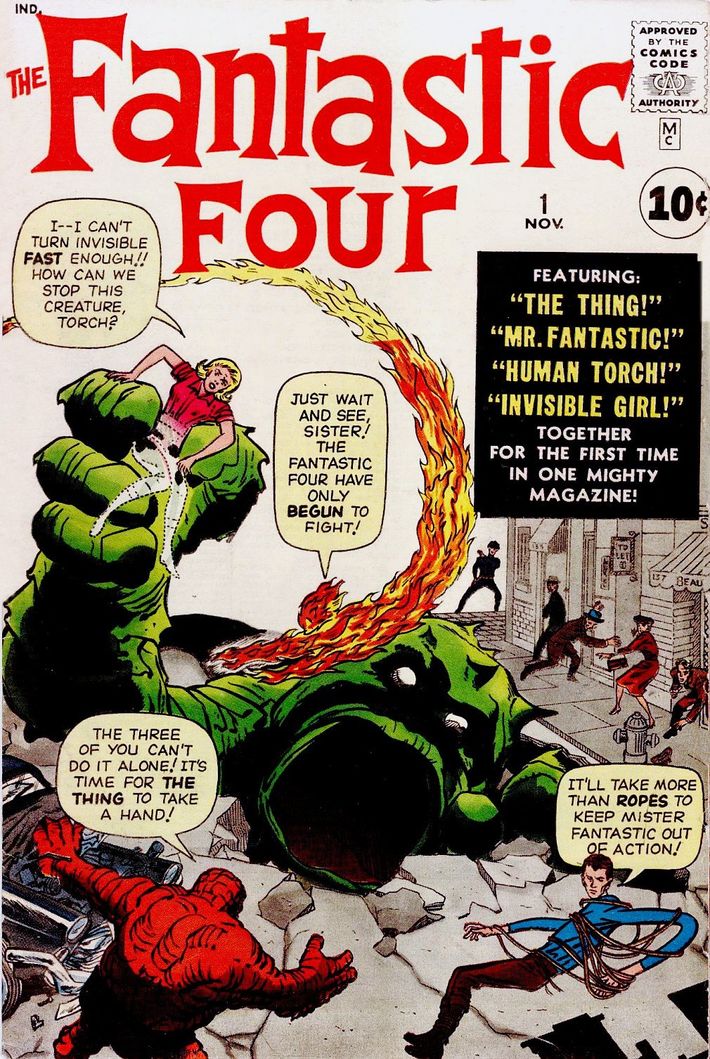

1963: The Fantastic Four

The almost-certainly apocryphal story behind the Fantastic FourÔÇÖs creation is that a top executive for Marvel and a top executive for DC were playing a round of golf and the DC exec bragged about how well Justice League of America issues were selling, so the Marvel exec ordered Stan Lee to create a superteam at Marvel ÔÇö leading Lee and his partner Jack Kirby to invent the Fantastic Four. Not only has this story been questioned repeatedly, it also completely obscures what makes the Four so world-changing: They were nothing like the Justice League. Right from their first few stories in 1963, they werenÔÇÖt gods: They were humans who had gotten in a scientific accident and got powers they never asked for. Indeed, the rock-covered monstrosity known as the Thing truly hated his condition and saw it as a curse. The other three members were all related by blood or romance, and were prone to infighting and resentment. Their ostensible leader, Reed Richards, was an arrogant prick. In other words, they were a family. Fantastic Four put this group of flawed and confused family members into struggles with incomprehensible scientific dangers, and issues flew off the stands. Their sales success kicked off the so-called Marvel Age ÔÇö a decade of creative wonder that gave birth to nearly all the characters youÔÇÖll see on the silver screen this weekend. But they werenÔÇÖt just a landmark: They were also unique and iconic in and of themselves, and remain vital to this day. ItÔÇÖs a damn shame that Marvel doesnÔÇÖt seem to want to keep them around these days.

1965: The Avengers in their second incarnation

The original Avengers ÔÇö Ant-Man, Wasp, Iron Man, Hulk, and Thor ÔÇö had assembled in 1963. But honestly, there wasnÔÇÖt a whole lot that was revolutionary about that lineup. Much like the Justice Society or the Justice League, they were an assemblage of existing characters brought together to fight a big threat. The first time the Avengers shifted superhero paradigms was in 1965, with Avengers No. 16. Long story short: Everybody left the team and Captain America (who wasnÔÇÖt even an original member) hired a new one, which included Hawkeye, Quicksilver, and Scarlet Witch. Just two years after the Avengers were created, they had a lineup with exactly zero people who had been there in their first appearance. In other words, this was the first time a superteam had acted like a sports team, holding on to a name and some difficult-to-describe essence despite a 100 percent turnover rate. That paradoxical mix of change and continuity would become a trope (sometimes even the norm) for every major subsequent superhero team.

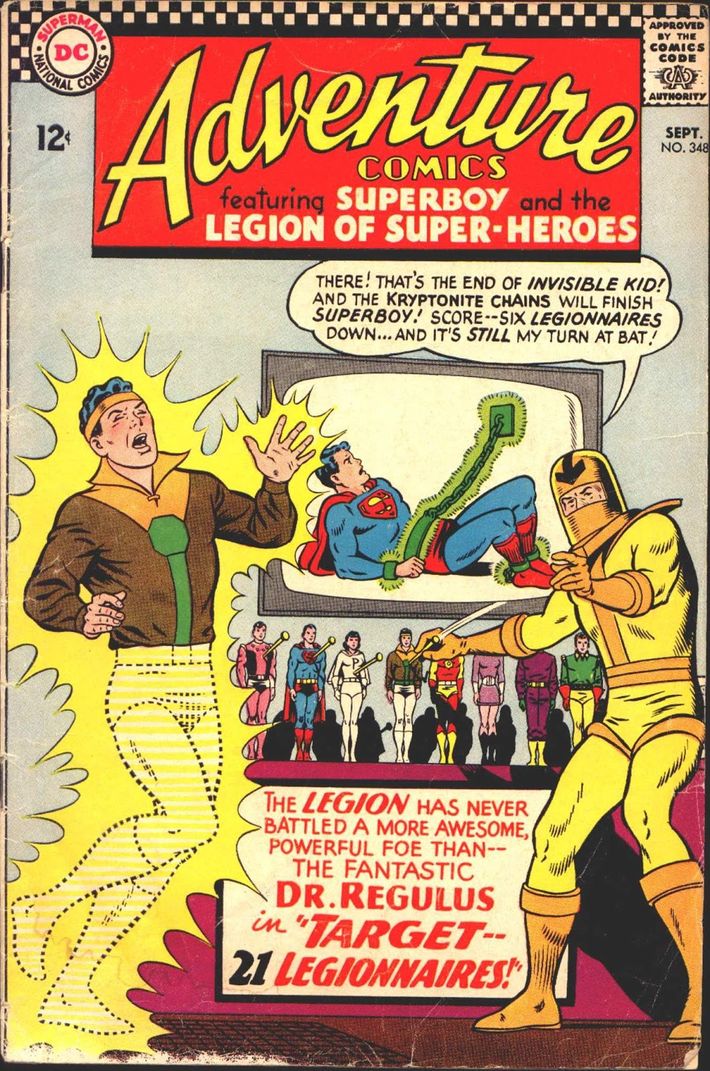

1966: The Legion of Superheroes at critical mass

The Legion werenÔÇÖt created in 1966 ÔÇö theyÔÇÖd been around since 1958 ÔÇö but in that year, they achieved what makes them so important in the history of superhero teams: a comically bloated membership. As of Adventure Comics No. 346, their lineup was [deep breath] Brainiac 5, Chameleon Boy, Colossal Boy, Cosmic Boy, Duo Damsel, Element Lad, Ferro Lad, Invisible Kid, Karate Kid (yes, you read that right), Light Lass, Lightning Lad, Matter-Eater Lad, Mon-El, Phantom Girl, Princess Projectra, Saturn Girl, Shrinking Violet, Sun Boy, Superboy, and Ultra Boy. The Legion were a group of space-based heroes from the far future, and what they lacked in individual personality, they made up for in sheer numbers and high-concept superpowers. The creative minds behind the Legion of the late ÔÇÿ60s and ÔÇÿ70s ÔÇö including notables like Curt Swan, Jim Shooter, and Dave Cockrum ÔÇö changed comics by declaring that there were no limits on how big or bizarre a team could be.

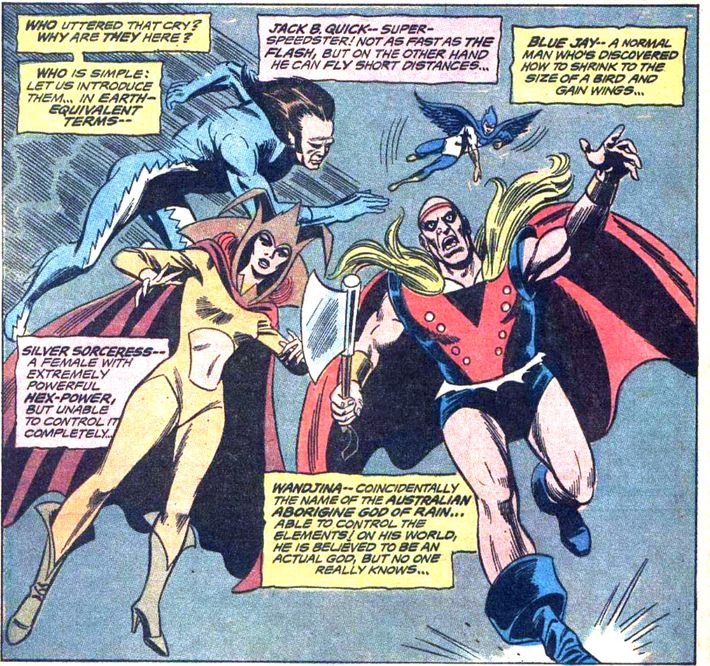

1971: Squadron Supreme / Champions of Angor

These teams are rip-offs, which is why they matter. In 1971, DC and Marvel decided to have an informal, unofficial crossover event ÔÇö instead of dealing with the licensing nightmare of having the Justice League meet the Avengers, each team just met a team of near-identical analogues (the Squadron Supreme and the superheroes of a world called Angor, respectively).* The Avengers didnÔÇÖt meet Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman ÔÇö they met Hyperion, Nighthawk, and Power Princess. The Justice League didnÔÇÖt meet Scarlet Witch, Quicksilver, and Norse weather god Thor ÔÇö they met Silver Sorceress, Jack B. Quick, and Australian weather god Wandjina. The stories themselves are forgettable and silly. But ever since then, this idea of playing with another universeÔÇÖs toys by building your own versions of them has been a powerful one. To this day, writers like MarvelÔÇÖs Jonathan Hickman and DCÔÇÖs Grant Morrison use Squadron and Angor characters to offer praise and critique for their rival companiesÔÇÖ ideas. In other words, these teams introduced a tool that allowed creators not to let intellectual-property laws get in the way of good storytelling.

*To the super-nerds out there: I am aware that the Justice League pastiche known as the Squadron Sinister had appeared in 1969. But their heroic Squadron Supreme counterparts have been used more often, and it seems more significant to talk about the time when Marvel and DC were working in sync.

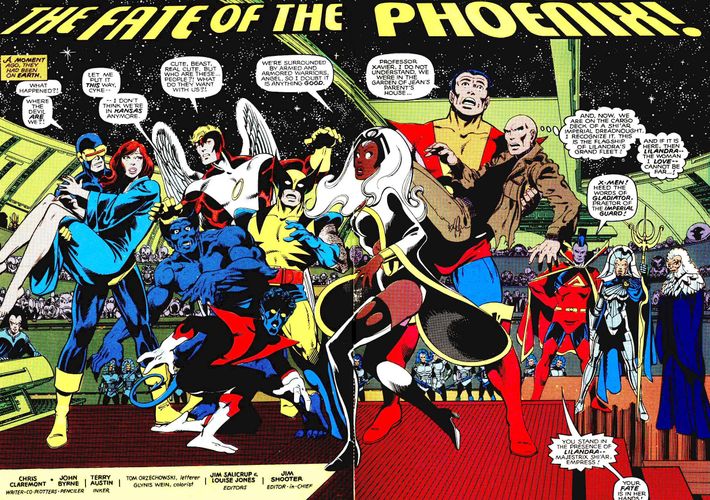

1979ÔÇô1981: The X-Men at the height of the Claremont and Byrne era

Technically, the X-Men were created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby in 1963. But when the average person closes her eyes and imagines the X-Men ÔÇö a motley, melodramatic, multiethnic squadron of outsider adventurers with the grizzled Wolverine among their rank ÔÇö what sheÔÇÖs seeing is the X-Men as they were under writer Chris Claremont and writer/artist John Byrne. And although they began their collaboration in 1977, the team they envisioned from 1979 to 1981 is what changed comics forever. Over the course of that stretch, the team membership was wall-to-wall icons: Wolverine, Storm, Cyclops, Jean Grey (as both Phoenix and Dark Phoenix), Nightcrawler, Colossus, and others. The interpersonal dynamics on this team ran the gamut: You had love triangles, racial tensions, opposites-attract friendships, mistaken identities, angry resignations, poignant mentorships, Oedipal rebellions, and tearjerking self-sacrifices. The full range of human emotion was on display, and the threats the team faced were unforgettable, ranging from the intergalactic (Dark Phoenix being put on trial for committing cosmic genocide) to the political (a xenophobic politician pushing for anti-mutant legislation) and beyond. And even at the very end, just before Byrne left, the team got one of its greatest gifts: the awkward, geeky, believable teen girl Kitty Pryde, who has become one of MarvelÔÇÖs greatest characters. This was, quite simply, the most thematically rich superhero team the world had ever seen, and arguably continues to hold that title today.

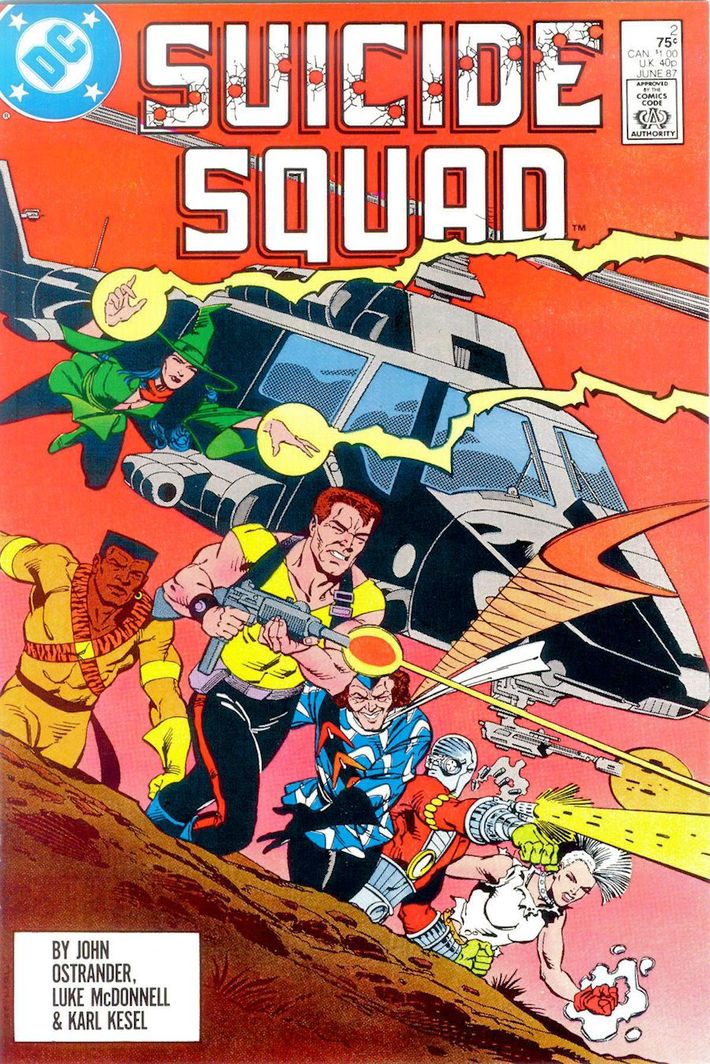

1987: Suicide Squad

Technically, itÔÇÖs incorrect to call the Suicide Squad a ÔÇ£superheroÔÇØ team, as theyÔÇÖre all villains. But if you leave that aside for a moment, you can see how the Squad, created by writer John Ostrander, changed the way teams get written in superhero comics. His concept was as elegant as it was brutal: The U.S. government snatches up small-time supervillains (like Deadshot, Bronze Tiger, Captain Boomerang, and Enchantress) and forces them to do high-risk black-ops missions in exchange for lightened punishments. And of course, if one of these nasty fellows happens to die during a mission, itÔÇÖs no skin off Uncle SamÔÇÖs nose. There had been supervillain teams in the past, but theyÔÇÖd never had the lead like this, and Ostrander gave even the worst of them a novel bit of pathos: After all, the cards were entirely stacked against them, they were being abused by an overreaching government, and they had nothing to do with choosing their teammates. On top of all that, the teamÔÇÖs ostensible leader ÔÇö a stocky, middle-aged, African-American, eternally pissed-off government handler named Amanda Waller ÔÇö despised everyone on the team. The Suicide Squad set a new standard for dysfunction, cynicism, and black humor in team superhero comicsÔÇÖ team dynamics.

1992: X-Men of the X-Men cartoon

In the parlance of the content-farm listicle: You know youÔÇÖre a ÔÇÿ90s kid if you remember the X-Men cartoon. ItÔÇÖs unlikely that weÔÇÖd be experiencing the current superhero-movie boom if weÔÇÖd never gotten the cheesy Saturday-morning antics of the early ÔÇÿ90s X-Men cartoon. The show was a massive hit, priming a generation of millennials for brightly colored, onscreen superhero insanity. Every kid with a working TV in America back then was at least somewhat familiar with this Day-Glo lineup: Cyclops, Jean Grey, Wolverine, Beast, Gambit, Rogue, Professor X, and everyoneÔÇÖs favorite mall-dwelling bubblegum enthusiast, Jubilee. This team struck an odd thematic balance that made them remarkable in superhero-TV storytelling: They werenÔÇÖt grimly dark (├á la Batman: The Animated Series), they werenÔÇÖt self-consciously campy (├á la the 1960s Batman show), and they werenÔÇÖt eye-rollingly sterilized (├á la Super Friends). Sure, they were stiff and over-the-top, but their stories had an epic scale, and their characters were emotionally engaging (at least for a child) while still being fantastical.

1999 / 2002: The Authority and the Ultimates

Ask any comics insider which comics artist is most responsible for the way superhero movies look today, and theyÔÇÖll give you one name: Bryan Hitch. Specifically, theyÔÇÖll cite his work on two revolutionary (and thematically very similar) series from the turn of the millennium: Image ComicsÔÇÖ The Authority and MarvelÔÇÖs The Ultimates. People described his style as ÔÇ£widescreen,ÔÇØ and anyone familiar with HitchÔÇÖs smooth contours, quasi-realistic action, and functional uniforms will instantly recognize the raw visual energy that Marvel harnessed for all its movies from Iron Man onward. (Plus, Hitch fatefully decided to model his Nick Fury on Samuel L. Jackson, leading to JacksonÔÇÖs subsequent casting in 2008.) But Hitch isnÔÇÖt the only reason these two teams are important. They are probably the two most cynical takes on superhero-team storytelling ever written. In 1999, legendary writer Warren Ellis invented the Authority as a team of heroes whose only ethical standard was ÔÇ£if the bad guys are dead and some of the civilians are still alive, then weÔÇÖve done our jobs.ÔÇØ Blackhearted Scotsman Mark Millar started writing the team after Ellis, but became most famous for reinventing MarvelÔÇÖs the Avengers in an Authority-like mold, under the name the Ultimates. This was a vision of Captain America, Iron Man, Hawkeye, and other classic do-gooders seen through the lens of horrific Bush-era neocon pragmatism. And so, in these two series, new precedents were set for how to put superheroes on the big screen and how to rip their moral veneer to shreds.

2003: Birds of Prey under Gail Simone

In a way, putting the Birds of Prey on this list is a bit of wishful thinking for the future. The comics world would be a better place if more teams were influenced by them. Birds of Prey had been created in 1999 on a simple (and vaguely cynical) premise: What if a pair of tough ladies of the DC universe (Oracle and Black Canary) worked together? But things changed when one of the best writers in the industry today, Gail Simone, took over the series in 2003, expanded the team, and gradually used it as a showcase for DCÔÇÖs deep bench of female characters. In 77 years of superhero comics, there have been virtually no all-female superhero teams ÔÇö and when they have existed, theyÔÇÖve often been written in demeaning ways by men. The Birds of Prey were light-years away from that garbage. There are still very few women-dominated superhero teams (though that has recently changed with the all-female lineup in X-Men and the upcoming A-Force), which just goes to show how vital and bold SimoneÔÇÖs Birds of Prey were.

2012: The cinematic Avengers

Sure, there had been a few superhero teams on the silver screen before The Avengers. But theyÔÇÖd all been introduced as teams right out of the box. The Avengers, on the other hand, was an assemblage of characters weÔÇÖd learned about across five other movies. It was, from that angle, a truly insane gamble: Audiences were expected to remember and care about a group of ridiculous individuals from movies they may or may not have seen over the preceding four years. Not only that ÔÇö they were supposed to be thrilled when those disparate characters stood together while a camera spun around them and they flexed their muscles. But thanks to the sheer totalitarian creative willpower of the Marvel Studios machine (as well as the swashbuckling fanboy inventiveness of Joss Whedon), it worked ÔÇö and in doing so, proved that you can make audiences crave a shared cinematic universe filled with superheroes whose apotheoses come when they team up. In other words, this was the movie that proved the formula devised for comics in 1940 could finally work on screens in the 2010s. As a result, every studio is clamoring to make its own shared cinematic universes, ripe for epic team-ups. For better or worse, The Avengers was the moment superhero teams conquered entertainment.