Inside the Sneaker Exhibition That’s Coming to the Brooklyn Museum

There’s a new theme every day on It’s Vintage. Read more articles on today’s topic: Sneakerheads.

As a curator at the Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto, Elizabeth Semmelhack often encounters the assumption that women make up the majority of shoe obsessives. It’s not true: She says the museum’s collections are evenly balanced with men’s and women’s footwear designs — but that notion is part of what inspired her to curate the first museum exhibition in North America to focus exclusively on sneakers. The show, “Out of the Box: The Rise of Sneaker Culture,” which is composed nearly entirely of men’s shoes, first opened at the Bata Shoe Museum last winter, and begins its four-city U.S. tour this July at the Brooklyn Museum.

Semmelhack says she’s interested in the relationship between sneakers and masculinity. “I find it interesting that men have been willing to put styles and colors on their feet that they would reject in other outfits,” she explained. The exhibition traces the evolution of the athletic leisure shoe back to its origins — the earliest shoe on display is a pre-vulcanized rubber overshoe made in Brazil in the 1830s — all the way to the present day. Semmelhack worked with sneaker collectors and archivists to put together a collection of greatest hits, from the original Converse All Star, to the first Adidas Stan Smiths, to Jeff Ng’s riot-inducing Pigeon Dunk. She spoke with the Cut about the history of sneakers and the way their cultural significance has evolved over the years.

As someone who’s studied footwear extensively, what about sneakers do you find particularly interesting?

Especially since the ‘80s, one of the things that has been so fascinating to me is that it’s at the sneaker level that men have been willing to take the greatest fashion risks. They’ve been willing to incorporate design and color into their footwear in ways they would shirk in other aspects of their attire. Sneakers are a means of enfranchising men into the fashion system — they allow men to break out of the uniformity of dress in which all men are expected to dress similarly. Think about a formal event: It’s expected that all the men will dress the same, whereas no two women could possibly show up in the same dress. With sneaker culture, men are expected to have different sneakers from everybody else. And if you take a simple outfit — jeans and a T-shirt — and wear that with a pair of Chuck Taylors, that says one thing. If you wear it with a pair of Air Jordans, that says another. There’s so much nuanced social and cultural meaning that is expressed through footwear choice.

How do you define “sneaker culture”?

Sneakers have been important expressions of status and masculinity [going] all the way back to the 19th century. Today, there’s a vocabulary of sneaker style that is easily recognizable from one sneaker guy to the next. In the ‘70s, televised basketball had this bravado that gave rise to players with a cult of personality. Sneaker brands became linked to these specific celebrities, and then you have people wearing footwear related to the success of these branded celebrities, and brand identity starts to become very nuanced. A pair of Converse high-tops, which are very retro, speaks to alternative lifestyles, whereas a pair of Jordan 28s are cutting-edge and forward-looking. Those two shoes alone suggest different interests, and different fashion statements. As sneaker culture and urban fashion grew in popularity, you have so many more sneaker companies and vocabularies, which establish group identities in smaller, niche ways.

What are the origins of sneakers?

I started the exhibition looking at rubber. It’s simply the sap of a tree. For a long time, Europeans thought of it as a novelty item: In fact, it gets the name “rubber” because it could erase pencil marks — and for a long time, that was pretty much the extent of what people thought rubber could do. If that sap is taken out of the Brazilian jungle and brought to Boston or New York, it melts in the hot summers, and it freezes and cracks in the winter. It was very elastic, but it was completely unstable. People became interested in the possibilities of rubber in the 19th century, and it’s the vulcanization of rubber that helps with industrialization.

Industrialization gives rise to industrialists — an emerging class with money. Sneakers became associated with status in the 19th century, because at that point, rubber is still quite expensive, and owning a pair also signified that you had time to play. At the same time, industrialists are starting to worry about the people that they employ: Urban places like New York City are being crammed full of immigrants who are working in factories and living in deplorable conditions, and the upper classes become concerned that moral degeneracy is going to be the byproduct of lack of fresh air and exercise. This happens at the same time that industrialization is making sneaker production cheaper and more widely available. Eventually, they do become somewhat democratized — increasingly, children are being required to wear sneakers for physical education, which is added to the school system. By the turn of the century, the sneaker is starting to become a ubiquitous part of the everyday wardrobe.

Where does the word sneaker come from?

It’s a child slang term that comes into use by the early 1870s. We’re surrounded by rubber, so we forget what an amazing material it must have been when it first came into use. The rubber soles mitigated the sound that shoes made, so kids called them sneakers — and that starts to be the common word that’s used in marketing.

Were early sneakers intended for both men and women?

Yes. They were designed for both men and women specifically because in the middle of the 19th century, lawn tennis comes into fashion, which was something that men and women could play together. Ideas around women’s rights are starting to foment at this time, and women are advocating that they get out and do things more, and there’s also a general idea that men and women and children should all exercise for health.

Do you see sneakers as a democratic form of footwear?

I think that’s sort of an untruth about sneakers. They do seem to be democratic — everywhere you go in the world today you see people in sneakers. But underneath that umbrella term sneakers is a minefield of meaning, and each sneaker type, and sneaker brand, carries with it slightly different meanings. With the incredibly wide variety of sneakers that are available today, even if you’re not interested in sneakers, you end up aligning yourself one way or another with a brand, style, and type.

How have sneakers evolved since their first incarnation?

When we look back at early sneakers, they look so simple: just a rubber sole and canvas upper. But these were cutting-edge technology — and I think that innovation and interest in the new has continued to push sneaker design since the first sneaker was made. By the middle of the 20th century, the sneaker has become, in many ways, the footwear of childhood, and it takes the “Me” generation of the 1970s to reestablish sneakers as a means of expressing status. I think that’s when sneakers really transformed from an object of sporting and leisure into a fashion accessory — people aren’t just jogging on Sunday in their bright Nike waffle trainers, they’re wearing the same waffle trainers to the disco that night. Throughout the entire history of the sneaker, you had designers trying to push the envelope to make footwear meet needs specific to athletes and athletics, but now it’s come hand in hand with demands from fashion. I think most sneaker designers still think of themselves as making footwear for elite athletes, but we know that the primary way the majority of sneakers function is as fashion footwear.

When did high-end designers start to embrace the sneaker?

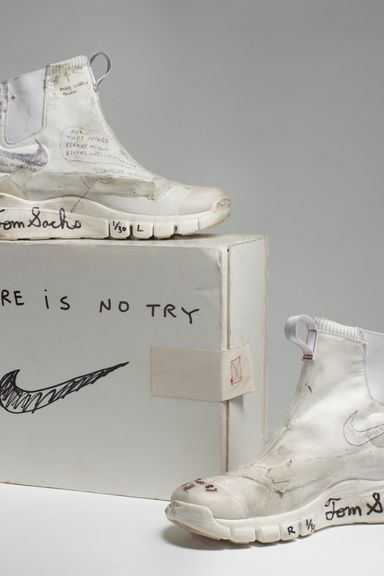

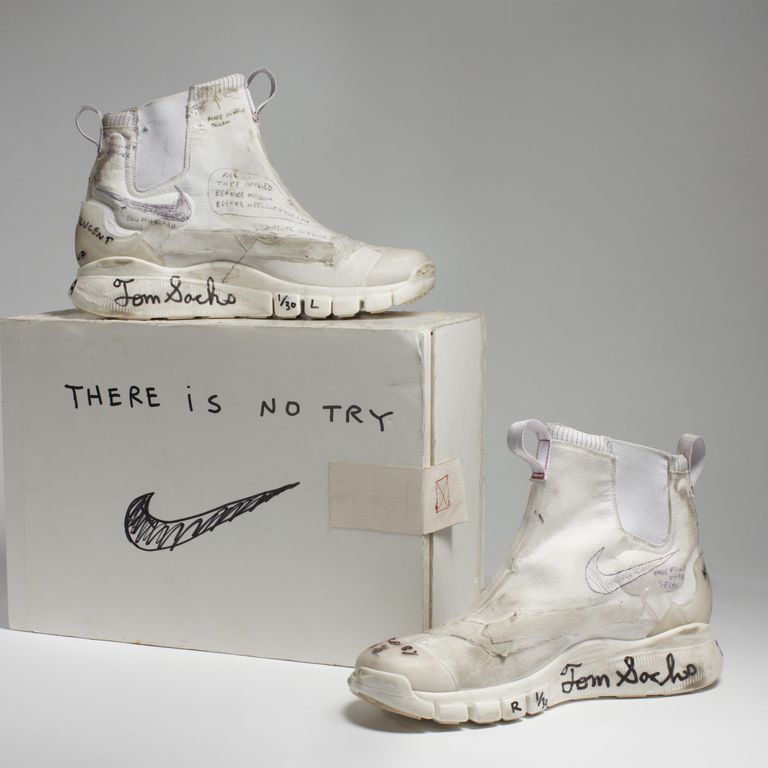

Gucci got into the game in the ‘80s, and Prada in the mid ‘90s. Yohji Yamamoto and Jeremy Scott did collaborations with Adidas. With the turn of the 21st century, the participation of high [end] designers doing collaborations with major sneaker producers accelerates exponentially.

It seems like the fashion world is particularly obsessed with sneakers right now. What do you attribute that to?

To me it seems two-pronged. One seems to be very retro-focused: You see a lot of nostalgia and a lot of successful old shoes that are being worn right now. There’s something kind of earnest about reusing footwear from the past. At the same time, so you have a lot of cutting-edge sneakers — particularly some of the collaborations that are happening with Rick Owens, Jeremy Scott, and Adidas. There’s mixed interest in the latest and greatest, and a very fond look at historic examples.

This interview has been edited and condensed.