Each month, Boris Kachka offers nonfiction and fiction book recommendations, and you should read as many of them as possible.

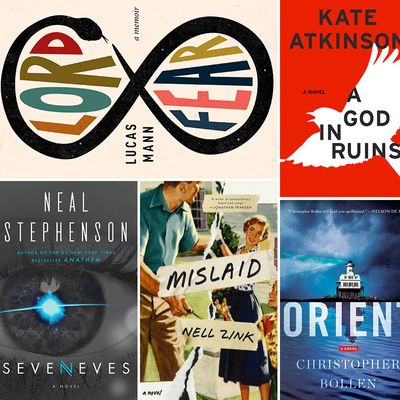

A God in Ruins, by Kate Atkinson (Little, Brown, May 5)

The great British writerÔÇÖs sideways sequel to Life After Life takes up the story of Teddy Todd ÔÇö RAF pilot, husband of a childhood sweetheart, father to a clueless hippie, and brother of Ursula, the repeatedly reborn protagonist of the previous novel. Here Atkinson is more subtly postmodern, shifting between past, present, and future in ways both subversive and perfectly organic. TeddyÔÇÖs unexpected survival of World War II and his safer, more ambivalent postwar life are revealed in carefully layered patches, showing that suspense can be about much more than what happens next.

Orient, by Christopher Bollen (Harper, May 5)

Residing in the Venn-diagram overlap of murder-mystery, literary stem-winder, and art-world roman ├á┬áclef, BollenÔÇÖs second novel draws on the pleasures of all three with barely a genre hiccup. A troubled teen is put up in a summer home in the titular North Fork town ÔÇö picture the Hamptons 40 years ago, when artists actually lived there and locals actually existed. As the bodies start piling up, he becomes a natural suspect. He didnÔÇÖt do it, of course, but who did? ItÔÇÖs a story worthy of Patricia Highsmith ÔÇö or, it turns out, the former editor-in-chief of Interview magazine.

The Green Road, by Anne Enright (W.W. Norton, May 11)

IrelandÔÇÖs first fiction laureate (as of January) doesnÔÇÖt rest on her laurels. This looping story of four siblings coping differently with the smothering embrace of their amusingly melodramatic mother ÔÇö mostly by fleeing County Clare, only to return once sheÔÇÖs widowed to reckon with failures great and small ÔÇö may be even better than its close cousin, The Gathering, which won the 2007 Booker prize. As locales shift from a stubby Irish village to AIDS-ravaged gay Manhattan and famine-torn Mali, so do the tone and point of view, over which Enright exercises perfect control.

The Book of Aron, by Jim Shepard (Knopf, May 12)

Shepard deserves attention far beyond the cozy circle of writers who worship him. In short stories, heÔÇÖs brought to throbbing life everyone from a passenger on the Hindenburg to a lonely creature in the Black Lagoon, and in the novel Project X he imagined the shooters of Columbine as the humans they were. Aron retells the well-known story of a doomed Warsaw Ghetto orphanage through the eyes of a very young and very flawed would-be survivor, eluding mawkishness and thereby evoking tears.

Lord Fear, by Lucas Mann (Pantheon, May 12)

MannÔÇÖs compact, almost New-Journalistic attempt to understand his older brother, who died of an overdose when Lucas was 13, isnÔÇÖt the first or even the tenth bereaved-sibling memoir, but its blend of taut novelistic style and documentary rigor makes it one of the strongest. Mann has a knack for tracking down uncomfortable truths (ÔÇ£Did you love him?ÔÇØ he asks his brotherÔÇÖs best friend) and burrowing in, like a metaphysical gumshoe, where others would turn away. Mann wants us to know his beautiful mess of a brother better than he ever did.

Mislaid, by Nell Zink (Ecco, May 19)

Some novels are full of wacky incident, others polished diamonds of compressed wit. ZinkÔÇÖs second novel keeps both modes in perfect balance. During the ÔÇÿ60s, a lesbian student in a Virginia womenÔÇÖs college marries a gay male poet, with disastrous results. Peggy, both tough as nails and loose of screw, absconds with their daughter, squats in a country cabin, and passes them both off as black. The bracing disconnect between sly, low-affect prose and Gothic strangeness recalls Flannery OÔÇÖConnor and Jean Stafford ÔÇö mid-century women you could imagine crossing paths with Peggy and shuddering.

Seveneves, by Neal Stephenson (William Morrow, May 19)

After wave upon wave of disturbingly realistic end-game scenarios from literateurs dabbling in apocalypse, an outlandish premise handled by a genre master comes as a relief. But Stephenson is hardly a harmless escapist, and Seveneves, in which the moon explodes at the start and the action shifts spaceward halfway through, tackles moral and scientific knots of great complexity. With a protagonist modeled on Neil deGrasse Tyson and social allegory worthy of H.G. Wells, Stephenson delivers both techno-futurism and old-fashioned fun.

Dietland, by Sarai Walker (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, May 26)

Leave aside the pastel cover and the shy, approachable narrator named Plum Kettle; WalkerÔÇÖs first novel leaves chick lit in the pixie dust, treading the rougher terrain of radical critique and shadowy conspiracies ÔÇö territory closer to Rachel Kushner than Helen Fielding. Plum is a 300-pound New Yorker, employed to answer a magazineÔÇÖs depressing fan mail and dead-set on gastric-bypass surgery until sheÔÇÖs entangled with a pro-fat collective and a terrorist cell known as Jennifer. Underneath the baggage ÔÇö physical and political ÔÇö is a character thoughtful, warm, and plausible enough to carry it off.