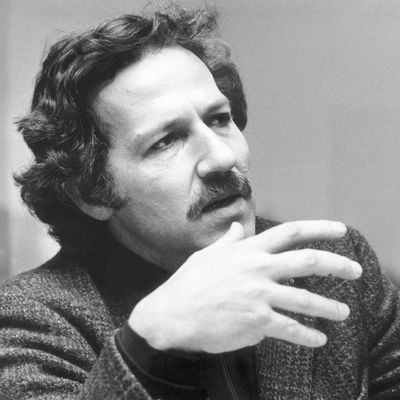

Werner Herzog.

Photo: Keystone-France/Getty

In 1974, director-madman Werner Herzog walked from Munich to Paris in a show of support for his friend, the cancer-stricken fellow filmmaker Lotte Eisner. During his epic trek, Herzog kept a blessedly typical (for him) mystical and philosophical diary, which was eventually published in 1978 as Of Walking in Ice. To commemorate his journey, University of Minnesota Press has published a new edition of the book — Herzog will also be speaking about the text on June 15 at Manhattan’s NeueHouse — and we have the first chapter for you here.

Saturday 23 November 1974

Right after five hundred meters or so I made my first stop, near the Pasinger Hospital, from where I wanted to turn west. With my compass I gauged the direction of Paris; now I know it. Achternbusch had jumped from the moving VW van without getting hurt, then right away he tried again and broke his leg; now he’s lying in Ward 5.

The River Lech, I said to him, that will be the problem, with so few bridges crossing it. Would the villagers row me across in a skiff ? Herbert will tell my fortune, from cards as tiny as a thumbnail, in two rows of five, but he doesn’t know how to read them because he can’t find the paper with the inter- pretations. There is the Devil, with the Hangman in the second row, hanging upside down.

Sunshine, like a day in spring, that is the Surprise. How to get out of Munich? What is going on in people’s minds? Mobile homes? Smashed-up cars bought wholesale? The car wash? Meditating on myself makes one thing evident: the rest of the world is in rhyme.

One solitary, overriding thought: get away from here. People frighten me. Our Eisner mustn’t die, she will not die, I won’t permit it. She is not dying

now because she isn’t dying. Not now, no, she is not allowed to. My steps are firm. And now the earth trembles. When I move, a buffalo moves. When I rest, a mountain reposes. She wouldn’t dare! She mustn’t. She won’t. When I’m in Paris she will be alive. She must not die. Later, perhaps, when we

allow it.

In a rain-sodden field a man catches a woman. The grass is flat with mud. The right calf might be a problem, possibly the left boot as well, up front on the instep. While walking, so many things pass through one’s head, the brain rages. A near-accident now a bit further ahead. Maps are my passion. Soccer games are starting, they are chalking the center line on plowed fields. Bavarian flags at the Aubing (Germering?) transit station. The train swirled up dry paper behind it, the swirling lasted a long time, then the train was gone. In my hand I could still feel the small hand of my little son, this strange little hand whose thumb can be bent so curiously against the joint. I gazed into the swirling paper and it gave me a feeling, as if my heart was going to be ripped apart. It is nearing two o’clock.

Germering, tavern, children are having their first communion; a brass band, the waitress is carrying cakes and the regular customers are trying to swipe something from her. Roman roads, Celtic earth-works, the Imagination’s hard at work. Saturday afternoon, mothers with their children. What do children at play really look like? Not like this, as in movies. One should use binoculars.

All of this is very new, a new slice of life. A short while back I stood on an overpass, with part of the Augsburg freeway beneath me. From my car I sometimes see people standing on the freeway overpasses, gazing; now I am one of them. The second beer is heading down to my knees already. A boy stretches a cardboard barricade between two tables with some string, securing it at both ends with Scotch tape. The regulars are shouting, “Detour!” “Who do you think you are?” the waitress says. Then the music starts playing very loudly again.

The regulars would love to see the boy reach under the waitress’s skirt, but he doesn’t dare. Only if this were a film would I consider it real. Where I’m going to sleep doesn’t worry me. A man in shiny leather jeans is going east. “Katharina!” screams the waitress, holding a tray of pudding level with her thighs. She is screaming southward: that I pay attention to. “Valente!” one of the regulars screams back, referring to a crooner of the good old days. His cronies are delighted. A man at a side table whom I took for a farmer suddenly turns out to be the innkeeper, with his green apron. I am getting drunk, slowly. A nearby table is irritating me more and more with its cups, plates, and cakes laid out but with absolutely no one sitting there. Why doesn’t anybody sit there? The coarse salt of the pretzels fills me with such glee I can’t express it. Now all of a sudden the whole place looks in one direction, without anything being there. After these last few miles on foot I am aware that I’m not in my right mind; such knowledge comes from my soles. He who has no burning tongue has burning soles. It occurs to me that in front of the tavern was a haggard man sitting in a wheelchair, yet he wasn’t paralyzed, he was a cretin, and some woman who has escaped my mind was pushing him. Lamps are hanging from a yoke for oxen. In the snow behind the San Bernardino I nearly collided with a stag—who would have expected a wild animal there, a huge wild animal? With mountain valleys, trout come to mind again. The troops, I would say, are advancing, the troops are tired, for the troops the day is done. The innkeeper in the green apron is almost blind, his face hovering inches from the menu. He cannot be a farmer, being almost blind. He is the innkeeper, yes. The lights go on inside, which means the daylight outside will soon be gone. A child in a parka, incredibly sad, is drinking Coke, squeezed between two adults. Applause now for the band. The fare tonight shall be fowl, says the innkeeper in the Stillness.

Outside in the cold, the first cows; I am moved. There is asphalt around the dung heap, which is steaming, then two girls traveling on roller skates. A jet-black cat. Two Italians pushing a wheel together. This strong odor from the fields! Ravens flying east, the sun quite low behind them. Fields soggy and damp, forests, many people on foot. A shepherd dog steaming from the mouth. Alling, five kilometers. For the first time a fear of cars. Someone has burned illustrated papers in the field. Noises, as if church bells were ringing from spires. The fog sinks lower; a haze. I am stock-still, between the fields. Mopeds with young farmers are rattling past. Further to the right, toward the horizon, many cars because the soccer match is still in progress. I hear the ravens, but a denial is building up inside me. By all means, do not glance upward! Let them go! Don’t look at them, don’t lift your gaze from the paper! No, don’t! Let them go, those ravens! I won’t look up there now! A glove in the field, soaking wet, and cold water lying in the tractor tracks. The teenagers on their mopeds are moving toward death in synchronized motion. I think of unharvested turnips but, by God, there are no unharvested turnips around. A tractor approaches me, monstrous and threatening, hoping to maul me, to run me over, but I stand firm. Pieces of white Styrofoam packaging to my side give me support. Across the plowed field I hear faraway conversations. There is a forest, black and motionless. The transparent moon is halfway to my left, that is, toward the south. Everywhere still, some single-engine aircraft take advantage of the evening, before the Goon comes. Ten steps further: the Business that Stalketh about in the Dark will come on Saint Oblivious Day. Where I am standing lies an uprooted, black and orange signpost; its direction, as determined from the arrow, is northeast. Near the forest, utterly inert figures with dogs. The region I’m traversing is infested with rabies. If I were sitting in the soundless plane right above me, I would be in Paris in one and a half hours. Who’s chopping wood? Is that the sound of a church clock? So, now, onward.

How much we’ve turned into the cars we sit in, you can tell by the faces. The troops rest with their left flank in the rotting leaves. Blackthorn presses down on me—as a word, I mean, the word blackthorn. There, instead, lies a bicycle rim entirely devoid of inner tube, with red hearts painted around it. At this bend I can also tell by the tracks that the cars have lost their way. A woodland inn wanders past, as big as a barrack. There is a dog—a monster—a calf. At once I know he will attack me, but luckily the door flies open and, silently, the calf passes through it. Gravel enters the picture, then gets under my soles; before this, one could see movements of the earth. Pubescent maidens in miniskirts are getting set to climb onto other teenagers’ mopeds. I let a family pass by me; the daughter is named Esther. A cornfield in winter, unharvested, ashen, bristling, and yet there is no wind. It is a field called Death. I found a white sheet of homemade paper on the ground, soaking wet, and I picked it up, craving to decipher something on the top side, which was turned toward the wet field. Yes, it would be written. Now that the sheet seems blank, there is no disappointment.

At the Doettelbauers’ everybody has locked up everything. A beer crate with empty bottles waits for delivery at the roadside. If only the shepherd dog (that is to say, the Wolf!) wasn’t so hot for my blood, I could do with the dog kennel for the night, since there’s straw in it. A bicycle comes and, with each full turn, the pedal strikes the chain guard. Guard rails next to me, and over me, electricity. Now it passes over my head crackling from the high voltage. This hill here invites No One to Nothing. Just below me, a village nestles in its lights. Far to the right, almost silent, there must be a busy highway. Conical light, not a sound.

How frightened I was when, before reaching Alling, I broke into a chapel to possibly sleep inside, and there was a woman with a St. Bernard dog, praying. Two cypresses in front let my fright pass through my feet into the bottomless pit. In Alling not a single tavern was open; I poked about the dark cemetery, then the soccer field, then a building under construction where window fronts are secured with plastic covers. Someone notices me. Outside Alling a matted spot—peat huts, it appears. I startle some blackbirds in a hedge, a large, terrified swarm that flies recklessly into the darkness ahead of me. Curiosity guides me to the right place, a weekend cottage, garden closed, a small bridge over the pond, barred. I do it the direct way I learned from Joschi. First a shutter broken off, then a shattered window, and here I am, inside. A bench along the corner walls, thick ornamental candles, still burning; no bed, but a soft carpet; two cushions and a bottle of undrunk beer. A red wax seal in a corner. A tablecloth with a modern design from the early fifties. On top of it a crossword puzzle, one-tenth solved with a great deal of effort, but the scribbling inside the margin reveals that every verbal resource had been tried. Solved are: Head covering? Hat. Sparkling wine? Champagne. Call box? Telephone. I solve the rest and leave it on the table as a souvenir. It’s a splendid place, well beyond harm’s way. Ah, yes. Oblong, round? it says here, vertical, four letters, ends with L in Telephone, horizontal: the solution hasn’t been found, but the first letter, the first square is circled several times with a ballpoint pen. A woman who was walking down the dark village road with a jug of milk has occupied my thoughts ever since. My feet are fine. Are there trout, perhaps, in the pond outside?

Excerpt courtesy Of Walking in Ice, Werner Herzog, translation by Martje Herzog and Alan Greenberg. U.S. edition published by University of Minnesota Press; U.K. edition published by Vintage. Originally published in German under the title Vom Gehem in Eis in 1978 by Carl Hanser Verlag. Copyright Carl Hanser Verlag 1978. English translation copyright Tamam Press 1980. Of Walking in Ice is published in the U.S. by the University of Minnesota Press at $19.95 and in the U.K. by Vintage Classics at 7.99 pounds.

Book Excerpt: Werner Herzog’s Of Walking In Ice