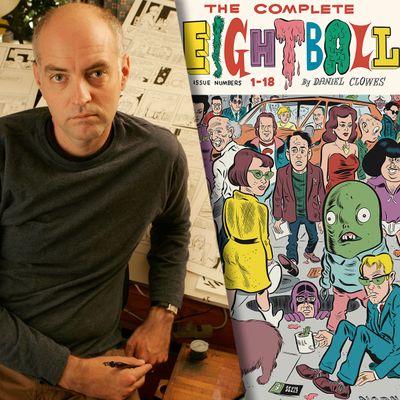

Say what you will about Shia LaBeouf: When it comes to artistic theft, at least he has good taste in his stolen goods. In 2013, he was revealed to have lifted a story by the venerable cartoonist Dan Clowes and used it, uncredited, in a short film. A bizarre battle ensued, involving cease-and-desist letters, insincere Twitter apologies, and cryptic skywriting. ItÔÇÖs all died down now, and itÔÇÖs safe to say that Clowes won in the court of public opinion. Plus, while LaBeoufÔÇÖs directing career has never taken off, ClowesÔÇÖs comics work is as vital as itÔÇÖs ever been.

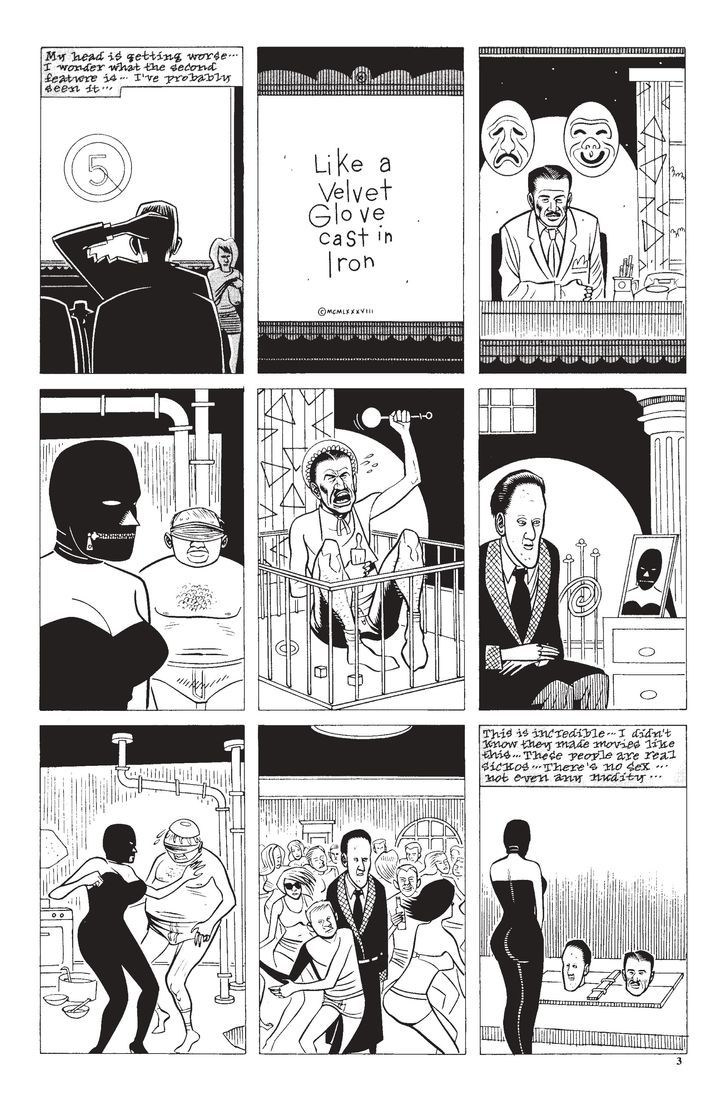

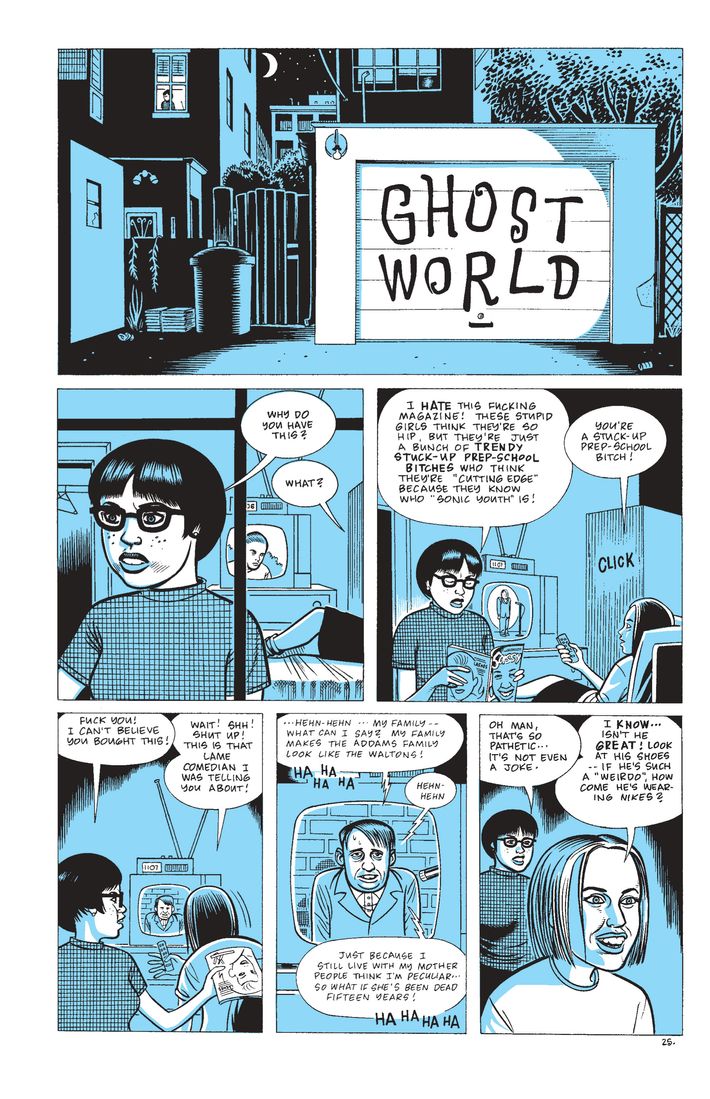

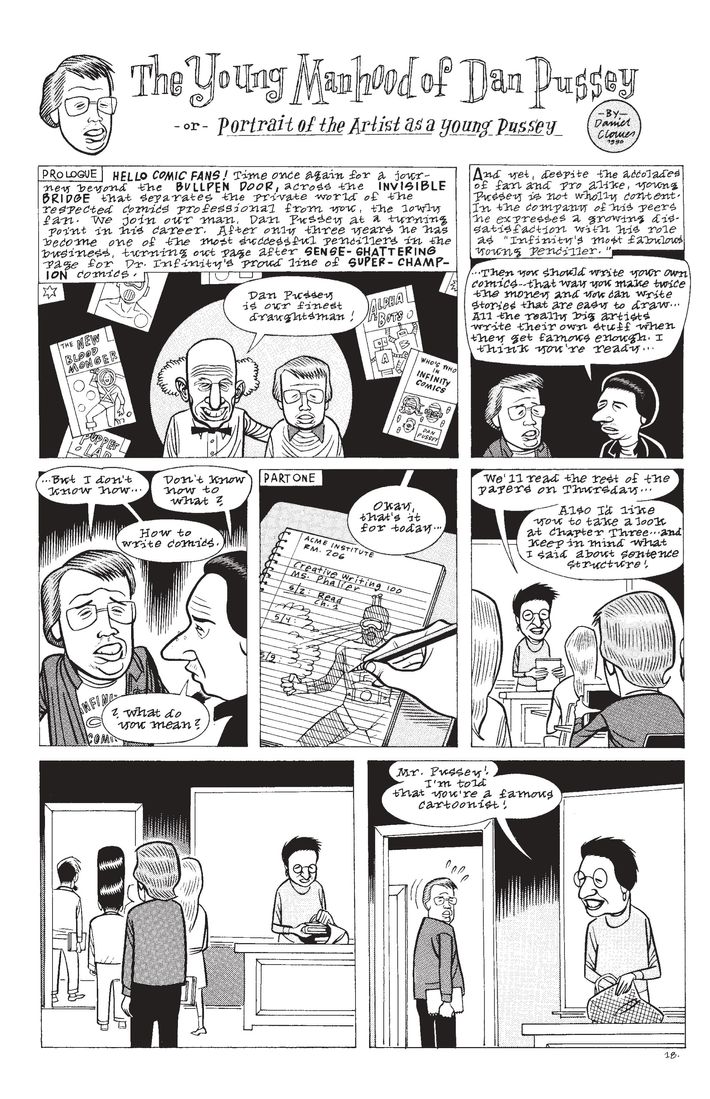

The writer/artist has been crafting unmistakable stories and artwork for nearly 30 years. Although heÔÇÖs perhaps best known for Ghost World ÔÇö a tale of adolescent friendship that he helped adapt into an acclaimed 2001 film ÔÇö his bibliography is extensive and varied. HeÔÇÖs penned everything from a surreal horror epic (Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron) to an Altman-esque ensemble caper (Ice Haven), from a vicious satire of the superhero-comics industry (Pussey!) to a sharp-tongued art-world satire (Art School Confidential).

But before those titles all became stand-alone books, they first appeared as serialized stories in ClowesÔÇÖs perioidic anthology comic┬áEightball.┬áTo mark the 25th anniversary of that series, Fantagraphics is releasing a two-volume compilation entitled┬áThe Complete Eightball┬áon June 17. The hefty collection follows ClowesÔÇÖs evolution from the bookÔÇÖs cynical beginnings up through his more relaxed later work, and even contains such odds and ends as his hand-drawn letters pages and in-house ads. We caught up with Clowes to talk about the LaBeouf incident, discovering Scarlett Johansson while casting Ghost World, his undying hatred of mainstream superhero comics, and his decades-old grudge against Jim Belushi.

To what extent was┬áEightball a desperation move when you originally launched it? You mention in the compilationÔÇÖs introduction that you were close to giving up on comics entirely.

Oh, it was very true. My first comic, Lloyd Llewellyn, was intended to be as commercial as possible. My publisher at the time said, ÔÇ£You have to have a main character, that character has to appear in every story, it has to catch on, and you have to go to comic conventions and do sketches of your one character so people know you from that.ÔÇØ I sort of took that at face value and thought, IÔÇÖm going to give it my best and do the most commercial thing possible. And of course, it was beyond un-commercial. ThereÔÇÖs no level low enough to describe it on the scale of commerciality.

So with Eightball I really thought, sort of in despair, IÔÇÖve given it my best shot, that failed miserably, so IÔÇÖm going to do the thing I really wanted to do in the beginning, which was sort of this little book that will house every idea that comes to mind. At best, I was hoping for three issues. I was really, really, praying they wouldnÔÇÖt just cancel it after the first one. No plan beyond that.

But how were you measuring success? How many copies did the best-selling issue of Eightball in this period sell?

ThatÔÇÖs the hilarious thing ÔÇö it was on such a tiny scale that sales almost didnÔÇÖt matter at first. The first issue, I think we probably printed 4,000 copies, and it probably sold out in a few months, which felt like a huge triumph. And then it got reprinted and reprinted, then the next issue was a little higher, and ultimately we got over 25,000 copies. It was almost like every single person who bought it had great importance to me. You judged it partly on the sales, but also partly on just the way people were responding to it. When Eightball came out, I had people come up to me [at] conventions [and] say, ÔÇ£This is really great, this is what IÔÇÖve been waiting for from you.ÔÇØ

Speaking of the small-but-committed readership: The letters pages are a delight, especially all the deranged hate-mail. Were there any pieces of written spite you particularly enjoyed revisiting?

I donÔÇÖt know that I had a specific one that would come to mind, but when I started putting [the collection] together, that was kind of the main impetus: I wanted all that stuff to be part of the comics. At that time, in the pre-internet era, I had, like, a responsibility to this community. It was almost this curated readership, where every single reader of Eightball had to be somebody who was willing to go to a comic store and dig through the adult books in the back, or they had to have some kind of curiosity to even know about it in the first place.

So anybody writing to me, I felt like I had a special connection to them. Those letters have such an incredibly powerful impact on me and other cartoonists. We used to reread them probably more times than the letter-writers would read the comic. Now if I get an email or something, it doesnÔÇÖt have any real impact anymore, itÔÇÖs not the same thing at all. I donÔÇÖt feel like IÔÇÖm being reached out to by somebody out in the wilderness.

Right, well, it gives a certain weight even to the hate mail; somebody had to sit down and handwrite or hand-type their vitriol.

At the time, I remember the hate mail really getting under my skin, but now I see itÔÇÖs all based on some deep emotional commitment to comics. I have no grudges against anybody. I know certain cartoonists who do still hate people who wrote them an angry letter in, like, 1983. ThatÔÇÖs deeper.

Speaking of grudges: Have you forgiven Shia LaBeouf?

I donÔÇÖt know. No, not really. I mean, I donÔÇÖt hold a grudge. I donÔÇÖt think about it that much. But I donÔÇÖt think what he did was really forgivable. I donÔÇÖt know that it matters that much if heÔÇÖs apologizing or whatever. I just hate the idea of anybody doing that to some young artist who couldnÔÇÖt hire legal representation. IÔÇÖm sort of the one guy who could deal with something like that, and it would be really possible for somebody with his amount of money and power to just crush some poor young artist if that happened to them, and I would hate to see that. So I donÔÇÖt think itÔÇÖs something that needs to be forgiven; I think itÔÇÖs something that always needs to be thought of as just a horrible thing to do.

YouÔÇÖve had more positive brushes with Hollywood, of course. The movie adaptation of Ghost World was a huge cult hit and made an icon out of the character of Enid Coleslaw. In the back matter for the Eightball collection, you say you were finishing the Ghost World comic while you were starting to work on the screenplay, and that there was movie Enid and there was comics Enid. How were they different in your head, and how did they inform each other?

Writing the dialogue for a movie is very different than writing a dialogue for comics. When youÔÇÖre writing dialogue for a movie, you have to start to hear an actorÔÇÖs voice in your head and imagine them actually saying the line. There are many lines in that screenplay that wouldÔÇÖve worked really well in a comic but that were such torture for a poor actor to say. WeÔÇÖd often write on the set and wind up cutting out 30 percent of a line just so a human being could say it. ThereÔÇÖs some line in Ghost World where Seymour [Steve Buscemi] says something like, ÔÇ£I assumed you wouldÔÇÖve thought of me as an amusingly cranky eccentric curiosity,ÔÇØ and every time I watch the movie IÔÇÖm like, How did he make that actually sound like a real line? ItÔÇÖs ridiculous that someone would actually say that.

And hey, you helped launch the career of Scarlett Johansson by casting her as EnidÔÇÖs friend Rebecca.

Yeah, I remember we were desperate to find Rebecca. We had found Thora Birch [to play Enid], and we just had no Rebecca. The studio, of course, wanted these mainstream actresses that wouldÔÇÖve been horrible. But also, we had all these audition tapes from totally unknown, small-time actresses. I was weeding through the stack because nobody else wanted to, and there was one where I thought, Gee, she was perfect! It was from Scarlett Johansson. But it was so hard to get them to agree to cast her. They finally they relented just ÔÇÿcause we were so adamant that she was the right one for it.

What was on her audition video? What monologue was she doing?

It was her just reading lines with her agent or manager or whatever. SheÔÇÖs sitting in a kitchen somewhere, in an office, I guess, and she just didnÔÇÖt seem to care at all. She was throwing out the lines like it was the real thing, and it was effortless, and you could tell sheÔÇÖs got the natural gift. Our producer said it was like seeing a young thoroughbred on the racetrack. It was kind of remarkable.

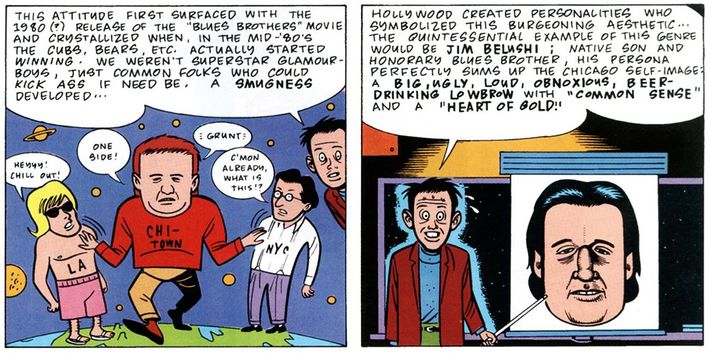

That reminds me: There are multiple points in these early Eightball stories where you go out of your way to dis Jim Belushi. What did you have against poor Jim Belushi?

He was just a symbol. I had nothing against Jim Belushi, really, but living in Chicago in the ÔÇÿ80s, he was sort of the quintessential symbol of the way the city thought of itself: as this kind of guy who was both working-class but also a slick Hollywood guy; a guy who was sort of fresh, honest, but not. It was very grating to me. It turns out later that many people agreed with me about that. And I feel sort of bad for him because it wasnÔÇÖt his fault, but he just came to embody this aspect of Chicago that I really disliked.

You also disliked the superhero comics industry, which is eminently clear in these early stories, especially your tales about Dan Pussey, a money-grubbing rube who creates trashy superhero stories. Why did you have such vitriol for superhero comics at the time?

It came from the way the whole business was structured back then.

Had you tried to make it in the superhero comics world?

No, it was half that kind of thing where, when youÔÇÖre a teenager, you really love something. You imagine some 12-year-old girl who loves One Direction or whatever, and ten years later, the thought of them, sheÔÇÖs just filled with hatred towards them because it reminds her of the way she was at this awkward age. I grew up reading superhero comics and had this certain love for them that was not┬ánecessarily┬árelated to the content. I just liked that Pop-art world of superhero comics, and then at a certain point, I learned about other comics and I completely lost interest in superhero comics.

So then I had to be starting my career and found myself immersed in that world, where that was my business context. It just felt depressive. It used to drive me crazy that I couldnÔÇÖt just tell anybody how to buy one of my comics. IÔÇÖd meet somebody and IÔÇÖd tell them about my comic and theyÔÇÖre like, ÔÇ£Oh, weÔÇÖre gonna get it,ÔÇØ and I wouldnÔÇÖt want to say, ÔÇ£Oh, you have to go to the comics store where itÔÇÖs like all superheroes and you have to go into the back, and thereÔÇÖs this little box in the back that says ÔÇÿAdult,ÔÇÖ there would be elf comics and maybe in the back thereÔÇÖll be a tattered issue of one of my comics.ÔÇØ

What were you into, superhero-wise, growing up?

IÔÇÖm 100 percent [a fan of Steve] Ditko, and still am. I like his Spider-Man, but I just loved the way he views the world, he has such a terror of the world.

HeÔÇÖs a Randian objectivist!

I feel like thatÔÇÖs just a layer of something way deeper. ThatÔÇÖs the response of somebody who has real trouble dealing with other humans, clearly. ThereÔÇÖs such a deep loneliness in his work that I respond to. The characters are always these singular guys walking through these foreboding urban landscapes. As a kid, thatÔÇÖs how I felt about the world.

But whatÔÇÖs weird is while youÔÇÖre doing Eightball, superhero comics had just gone through this renaissance where guys like Alan Moore and Frank Miller were elevating the medium.

I couldnÔÇÖt have been less interested. I have nothing but contempt for it. Nothing at all like that had interested me. I was interested in the opposite of that, really. That sort of stuff just seemed like pure schlock to me.

Have you made your peace with superhero comics in subsequent decades?

ItÔÇÖs nothing IÔÇÖm interested in. IÔÇÖm just not interested in it. I like the Pop-art aspect from my childhood, but I donÔÇÖt care about the movies or the comics. I couldnÔÇÖt force myself to get interested in it now.

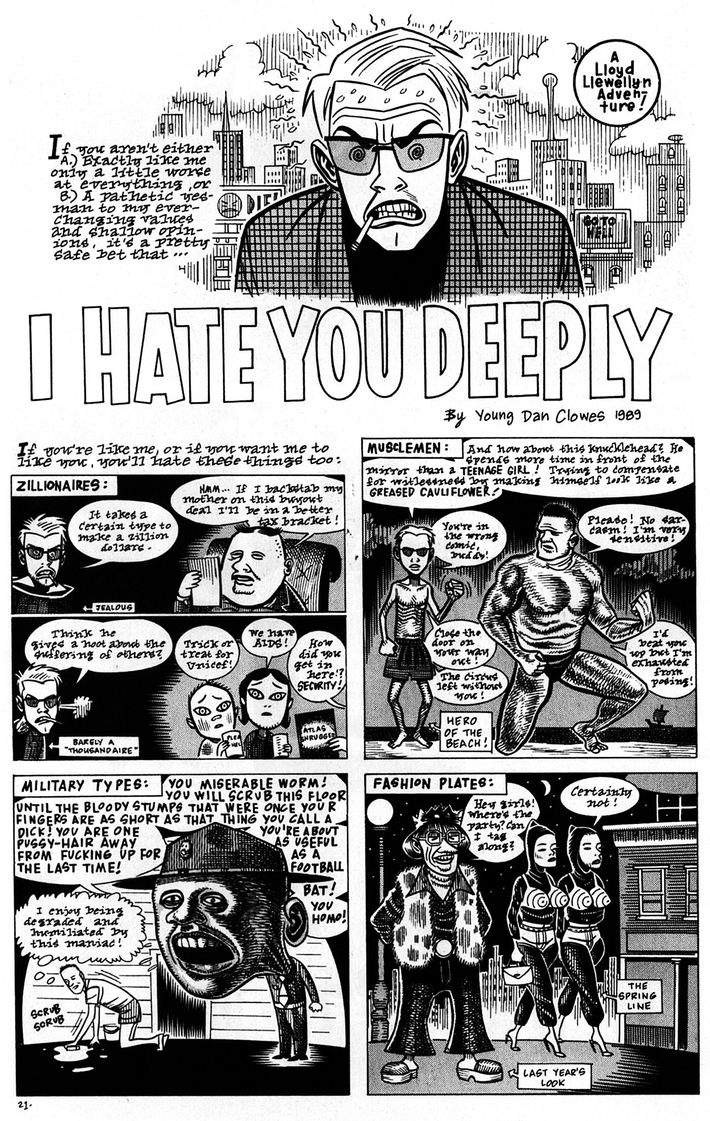

In these early pieces, your ire isnÔÇÖt limited to superheroes. You have stuff like ÔÇ£I Hate You Deeply,ÔÇØ which is just pages and pages of a narrator listing all the things he doesnÔÇÖt like about the world. When you were doing those strips, how did you hold on to your anger while making them? DoesnÔÇÖt your rage start to dissipate over the course of actually drawing the comic?

ThatÔÇÖs a very interesting thing to notice, and itÔÇÖs something I think about a lot because comics are not spontaneous. It doesnÔÇÖt have the immediacy of, say, music or stand-up comedy, where you can get an inspiration and throw it out there and get an immediate response, all in the same emotional beat. You really have to plan ahead for what emotions you might have for the next two weeks.

The thing with those ÔÇ£I Hate You DeeplyÔÇØ type of stories was finding the moments where I was the most angry or where I said things that were totally irrational, and giving those moments permanence in the comics. But certainly, at the time I was doing it, I thought those strips were hilarious. I never really thought of it as, IÔÇÖm infecting the world with my bile and anger. Now, looking back on it, with some of the opinions IÔÇÖm like,┬áOh yeah, I still think that. With some of them IÔÇÖm like, I donÔÇÖt even know what that was about. I donÔÇÖt even remember what I was thinking on that Tuesday when I wrote this.

But in those rants, you did point out how horrible mullets were, and you did that way before it was cool to do so.

ThatÔÇÖs right. I want credit for that because I really did precede anybody else that I remember.

Finally: With the superhero-movie explosion in full force, what do you think Dan Pussey would be up to today?

You know, itÔÇÖs funny, ÔÇÿcause in that one story I did, ÔÇ£The Death of Dan Pussey,ÔÇØ it takes him into the future, where comic books are completely forgotten. But you know what? HeÔÇÖd be king of the world right now. This is his era.