Each month, Boris Kachka offers nonfiction and fiction book recommendations, and you should read as many of them as possible.

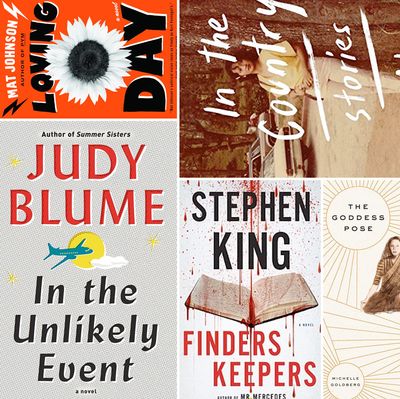

Loving Day, by Mat Johnson (Spiegel & Grau, June 2)

Recent race-based satires like Paul BeattyÔÇÖs The Sellout and Nell ZinkÔÇÖs Mislaid might prime you to expect something more antic from Johnson, whose 2011 novel Pym set a new bar for racial postmodernism masquerading as comic adventure. But this unsentimental journey through a biracial manÔÇÖs tangled Philadelphia roots is more grounded and deliberate. The wit and wildness of his language and characters are leavened with longing, as well as intimations of recovery on a scale as large as society and as small as narrator Warren DuffyÔÇÖs mixed-up soul.

Finders Keepers, by Stephen King (Scribner, June 2)

When King has fun, so do his readers, even ÔÇö or especially ÔÇö when his fun is at their expense. As Misery had its No. 1 fan, Finders Keepers has a resident psycho, Morris Bellamy, who stalks a reclusive Salinger stand-in, John Rothstein, then steals his cash and unpublished sequels. In this, KingÔÇÖs own sequel to Mr. Mercedes (and book two in a trilogy), BellamyÔÇÖs nemesis turns out to be another much nicer fan who discovers his stash. Their final confrontation, involving MercedesÔÇÖs three detective heroes, is ÔÇö like KingÔÇÖs crazy fan base ÔÇö well earned.

In the Country, by Mia Alvar (Knopf, June 16)

Tracking Filipinos at home and in diaspora across several continents, social classes, and decades, AlvarÔÇÖs debut story collection is so well-drawn and plot-rich that you almost wish it were a novel. But then Alvar wouldnÔÇÖt have been able to cram in so many disparate voices and painful ironies: a New York pharmacist smuggling drugs on flights back home to palliate his dying father; a set of housewives in Bahrain who throw parties for their poorer landspeople; an office cleaner in the World Trade Center in the summer of 2001.

Book of Numbers, by Joshua Cohen (Random House, June 9)

ÔÇ£If youÔÇÖre reading this on a screen, fuck off,ÔÇØ writes Joshua Cohen (the narrator, not the author) at the beginning of this sometimes difficult, frequently hilarious high satire of our digital world. ÔÇ£CohenÔÇØÔÇÖs job of ghostwriting a secretive tech guruÔÇÖs autobiography allows Cohen (the writer) to run a ten-foot skewer through Silicon Valley. Yet that first line is a reddish herring, because this is a stranger, more layered critique than, say, Dave EggersÔÇÖs The Circle┬áÔÇö a book after William GaddisÔÇÖs heart that will be around well after most summer reads have been recycled (or deleted).

The Goddess Pose, by Michelle Goldberg (Knopf, June 11)

ItÔÇÖs hard to believe that the life of Indra Devi, the Zelig who helped turn yoga into the plaything of midcentury Hollywood, NoriegaÔÇÖs Panama, and the rest of the world, hasnÔÇÖt been made into a blockbuster film, never mind a fascinating work of nonfiction. Without idolizing or condemning her, Goldberg evokes DeviÔÇÖs complicated nature as deftly as she does the Russian Empire, Weimar Berlin, occupied Shanghai, and so many of the other places where Devi worked, loved, and proselytized before her life ended at 103, not long after the century she helped define.

In the Unlikely Event, by Judy Blume (Knopf, June 2)

The taboo-breaking authorÔÇÖs first novel for adults in 17 years draws on a communal tragedy you could easily imagine in the hands of Philip Roth. In 1951, when Blume was 14, three planes crashed within two months in her hometown of Elizabeth, New Jersey. BlumeÔÇÖs semiautographical treatment isnÔÇÖt Rothian at all, but focuses Blumishly on personal transformations ÔÇö especially those of two girlfriends grappling with virginity and the mysteries of grown-ups. Yet there are adult struggles, too, and a satisfying portrait of a time when many things really were taboo ÔÇö a time before Judy Blume.

Death and Mr. Pickwick, by Stephen Jarvis (FSG, June 23)

Historical fiction always contends with the problem of how to fit research and hindsight seamlessly into an in-the-moment narrative. Jarvis meets the challenge ingeniously in this long semi-alternate history of DickensÔÇÖs literary debut, The Pickwick Papers. His main character is a researcher hell-bent on proving that BozÔÇÖs first character was stolen from the now-forgotten illustrator Robert Seymour. In the process, he unfurls the social canvas of 1830s England in its boozy, frumpy glory, with a knack for puns and character sketches (and serial digressions) his idol would likely admire.