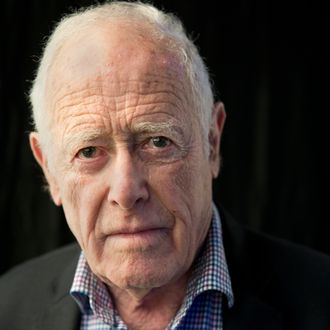

James Salter, the highly acclaimed but never commercially popular writer, has died at 90, the New York Times┬áreports. Salter chronicled the ennui of postwar America and the often toxic nature of masculinity, from his debut novel The Hunters (1956) to his controversial classic A Sport and a Pastime (1967), a sensuous sylph of a novel that SalterÔÇÖs publishers viewed as being akin to ÔÇ£a pair of dirty socks,ÔÇØ to the Salter-scripted Robert Redford film Downhill Racer (1969) and the PEN/Faulkner-winning collection Dusk and Other Stories.

As Pulitzer-winning writer Richard Ford once said, ÔÇ£It is an article of faith among readers of fiction that James Salter writes American sentences better than anyone writing today.ÔÇØ┬áThose beautiful, fluid sentences were usually unburdened by ornate flourishes, yet somehow Salter always seemed to dig at truths deep and dark┬áÔÇö┬áhis writing sharp enough to pierce something unfathomably heavy. His most recent novel, the critically heralded All That Is, depicts the exploits of the whip-smart Philip Bowman, who assimilates into the halcyon days of the publishing industry in postwar New York, bedding women, traversing the strange concrete jungle in so many taxis. The novel, at once sensitive yet stoic, begins:

All night in darkness the water sped past.

In tier on tier of iron below deck, silent, six deep, lay hundreds of men, many faceup with their eyes still open though it was near morning. The lights were dimmed, the engines throbbing endlessly, the ventilators pulling in damp air, fifteen hundred men with their packs and weapons heavy enough to take them straight to the bottom, like an anvil dropped in the sea, part of a vast army sailing towards Okinawa, the great island that was just to the south of Japan. In truth, Okinawa was Japan, part of the homeland, strange and unknown. The war that had been going on for three and a half years was in its final act. In half an hour the first groups of men would file in for breakfast, standing as they ate, shoulder to shoulder, solemn, unspeaking. The ship was moving smoothly with faint sound. The steel of the hull creaked.

SalterÔÇÖs works didnÔÇÖt sell very well, but as seems almost appropriate, they came to be regarded as masterpieces slowly, over time, not unlike the deliberate pacing and rhythm of his prose. When the once-reviled A Sport and a Pastime was rereleased in 1985, Reynolds Price wrote in the New York Times Book Review, ÔÇ£In its peculiar compound of lucid surface and dark interior, itÔÇÖs as nearly perfect as any American fiction I know,ÔÇØ a line that has been oft-repeated in ensuing years.

Salter is survived by his wife, Kay Eldredge.