This article appeared in the April 8, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.

In the dark Bronx days of the Great Depression, I lived on a street named after the brook or burn that once flowed through it. I came down the front steps of my house into a world that was sunny, warm, and clean. Nobody in the neighborhood owned a car, and so the street belonged to the kids. It was our stickball field, our flea market. We flipped pennies against a wall, traded baseball cards, played skelly with soda-bottle caps; we opened our hands for the delicate art of box ball, and abandoned ourselves to the wild neighborhood wars of ringolevio. An eminence who lived on our block was a captain in the Sanitation Department, which is why every other day in summer, the water wagon came grinding up the street, spraying from the sides of its tank a beautiful spreading arc of glistening rainbows that seemed ethereally to be herding this beast of a truck like a pair of angels. And when the water wagon turned the corner and was gone, the street was suddenly quiet except for the bubbling rivulets of water running along the guttered curbs, carrying with it our fleets of walnut shells and ice-cream sticks as we scurried along to see how far they would go before running aground.

At one end of the block, the lower north end, for the Bronx here was all gentle hills and dales, was our school, P.S. 70, with its block-long schoolyard where every Sunday morning the fathers would play softball, the big hitters capable of belting home runs all the way over the high chain-link fence atop the twenty-foot concrete wall on the next block east.

At the south or high end of our slightly sloping block was what we called the Oval, one of a row of small plazas with benches and water fountains and beds of yellow and white tulip bulbs that divided Mount Eden Avenue on its way to the Grand Concourse. The mothers sat with their carriaged babies and would look on disapprovingly as I encouraged my dog Pinky to drink from the fountain, which she did by standing on her hind legs and lapping the stream of water as I pressed the handle for her.

But the Oval wasnÔÇÖt the real thingÔÇöthe real thing was Claremont Park, on the other side of Mount Eden Avenue, a glorious true preserve you got to by walking up a flight of stone steps to find yourself under tall trees and among shaded glens, winding paths, and patches of mysteriously tended flowers. There were ant colonies for my study, and on a certain week in the summer ÔÇ£The Farm in the Park,ÔÇØ a traveling exhibit run by the Parks Department in which pint-size barns and corralled straw beds were stocked with goats and sheep and rabbits set out for children to pet. I outgrew ÔÇ£The Farm in the ParkÔÇØ very quickly, feeling superior to the babies who loved it. But it interests me how, in the darkest days of the Depression, the city gave all it had to the children. P.S. 70 was fully equippedÔÇötextbooks, maps, turtles in their bowls. The teachers were academically overqualified, as who wouldnÔÇÖt be in the competition for jobs.

This part of the Bronx, new and open under the sky, had flourished in the few years since the independent subway line had been extended from Manhattan, making possible a fast commute into town. This was the faux-rural Borough of Escape for all the folks working their way out of the Lower East Side. And it was an equitable society, everyone penniless together, scraping along.

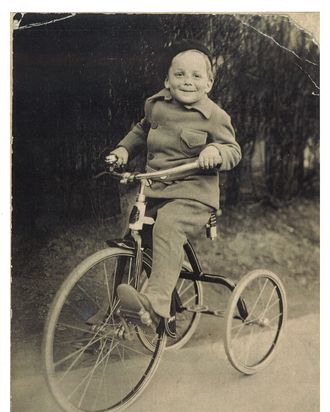

Serious issues of survival spread in concentric circles from my house all the way to Europe. I could eavesdrop with the best and knew everything. But there is a natural selfishness to childhood, and no matter how much I learned of fearsome adult life, I lived instinctively in the moment, as all children do. And what moments there were! I marked the seasons by the coming to our block in June of Joe the Ice Man, who sold ices from his pushcart, ceremoniously pouring a nameless red syrup over shaved ice in pleated paper cups, and who in December appeared transmogrified as Joe the Sweet Potato Man, his cart fitted with a charcoal stove for roasting the hot cloven sweet potatoes that he sold wrapped in newspaper cones. Spring came with the house sparrows on our windowsills, fall with a new composition notebook into which I had not yet drawn my air armada or my name in block letters.

Winter was finally the time of such exertion as to constitute a triumph over nameless cold evil. As dogged as Shackleton striding across Antarctica, my friends and I trekked the neighborhoods looking for the best snow street, and when we found it we took off with no further ceremony, running all out, our Flexible Flyers held aloft and, attaining launch speed, we threw ourselves and our sleds through the air and bellywhopped our way down the snow-packed avenue, the sticking snow flying into our grins and all the powers of life humming in our skinny little heart-pumping bodies.