Wednesday night at New York CityÔÇÖs Film Forum, Christopher Nolan premiered his new short documentary about the Brothers Quay ÔÇö a pair of legendary experimental animators ÔÇö and afterward took the stage with them to discuss their work. The occasion was opening night of a touring 35mm program of Brothers Quay films, which was curated by Nolan and will be at Film Forum through Tuesday. It features three of the QuaysÔÇÖ best-known shorts ÔÇö 2000ÔÇÖs Karlheinz StockhausenÔÇôscored reverie of madness In Absentia, the playfully degenerate 1990 film Comb, and the noirish nightmare Street of Crocodiles (1986), possibly their masterpiece.

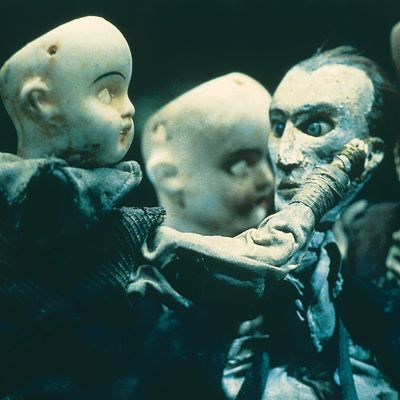

NolanÔÇÖs film, simply titled┬áQuay, makes no attempts to replicate the animatorsÔÇÖ much-imitated style. Instead, it shows Timothy and Stephen Quay ÔÇö identical twins, in case you were wondering ÔÇö at their studio in England, discussing their craft. As anyone who has seen even a minute of their footage can tell you, the QuaysÔÇÖ surreal films, shot with refashioned dolls, handcrafted miniature sets, and other found objects, are dense with atmosphere but not heavy on narrative; the films depict states of mind instead of telling linear stories. You could read a plot description of Street of Crocodiles, but it would do you little good; the film focuses on the unhinged movements of tiny objects and the transformation of dolls to create a world in flux, hovering playfully and disturbingly between particulate longing and body horror.

But the films are also exceedingly well-made, and NolanÔÇÖs focus on the sometimes-backbreaking labor involved is more than welcome. In his documentary, the Quays talk about how they often have to blast light into small mirrors treated with underwear-wash residue (no, really) to get the muddy, precise pinpoints of light that appear throughout their work. Or how they dab extra-virgin olive oil on parts of their puppets to give them a lived-in quality ÔÇö ÔÇ£to highlight the soul of the puppet.ÔÇØ

Perhaps the filmÔÇÖs most startling moment comes when the Quays demonstrate how they do tracking shots, and the ÔÇ£havoc on your backÔÇØ it causes: They have to move the track a millimeter, then animate a figure one frame, then move the track again, then animate another frame, all the while also accounting for pulling focus, potential changes in light, and any other camera movements, such as a boom or crane up. (They pointed out in the post-screening Q&A that it takes 600 frames to create 24 seconds of animation ÔÇö thatÔÇÖs 600 millimetric tracking shifts combined with 600 millimetric object movements.)

Appropriately, the Q&A on Wednesday, moderated by a clearly giddy Nolan, focused largely on craft, but also on the collision between serendipity and meticulousness. The Quays recalled that one of the reasons for the odd quality of the light in In Absentia had to do with the fact that they used natural light as it came through one of the east-facing windows of their studio. At the time, Timothy Quay didnÔÇÖt have a home, and had taken to sleeping in the studio. So they would pre-align the mirrors they were using to capture and direct the light, and Timothy would wait for the morning sun to hit the set. But since the sun changes position from day to day, they also had to track the lighting to make sure that it was consistent.

All that seemed to be for naught, however, when they saw their footage and realized that the light still had a weird flickering quality, since England rarely has purely sunny days. But, as Nolan pointed out, ÔÇ£the wildness of the energy of the lightÔÇØ contrasts and works in tandem with ÔÇ£the control of the imagesÔÇØ in In Absentia┬áÔÇö perfect for a film that, after all, is ostensibly about entering the mind of a schizophrenic. (The film was based on the story of a turn-of-the-century patient in an asylum who wrote the same love letter to her husband every day.)

The Quays seemed to delight in revealing some of their tricks and the studied amount craft and literally mathematical precision that goes into creating works that, on the surface, seem so free-form, almost stream-of-consciousness. But, as they pointed out, they also leave themselves open to uncertainty. They discussed how one of the climactic moments in Street of Crocodiles came from a visit to a zoo in Regents Park right when they were struggling with how to finish the film; a stray movement from a lizard in a cage as it looked directly at them gave them the idea for a key repeated movement that, in its own absurd way, brings the action of the film together.

But does looking under the hood of these wild, unique films in this way somehow reduce their magic? Nolan, a Brothers Quay fan since his teens, didnÔÇÖt seem to think so. ÔÇ£When I found out the technique behind the illusions,ÔÇØ he said, ÔÇ£the illusions became even more unlikely and extreme.ÔÇØ