Each month, Boris Kachka offers nonfiction and fiction book recommendations. You should read as many of them as possible.

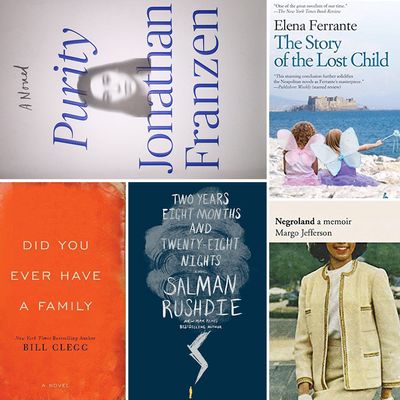

The Story of the Lost Child, by Elena Ferrante (Europa Editions, September 1)

The four books in FerranteÔÇÖs Neapolitan series, of which this is the dark and clamorous finale, are really just one thick novel, but its piecemeal translation has allowed the pseudonymous authorÔÇÖs American cult to swell to Knausgaardian proportions. YouÔÇÖd have to start from book one in order to fully appreciate the complex friendship at its core, between intellectual Elena and tempestuous Lila, two women fated to live very different lives. In part four, Elena and her cohort age from their turbulent 30s to their 60s, raise and struggle with children, and seek solace in the unlikeliest place ÔÇö the vibrant, violent Naples of their birth.

Fates and Furies, by Lauren Groff (Riverhead, September 15)

Any story is in the telling ÔÇö a recurrent theme in GroffÔÇÖs third novel about a couple blissfully and disastrously married. Lotto and Mathilde, shown consummating their elopement in the opening pages, have a seemingly mythic bond (the Greeks play a large thematic role), but we suspect it isnÔÇÖt so. The first half of GroffÔÇÖs many-faceted gem, titled ÔÇ£Fates,ÔÇØ belongs to Lotto, who goes from failed actor to famous playwright, from philanderer to not-quite-ideal husband. In the second, ÔÇ£Furies,ÔÇØ distant Mathilde finally speaks, spilling stratagems and secrets and rage. As everything twists and unravels, Groff collapses the dichotomy between the domestic and the epic.

The Wake, by Paul Kingsnorth (Graywolf, September 1)

The very small list of books that succeed in both reinventing a language and telling a great story gets longer with this account of the 1066 Norman invasion of England, unreliably narrated by one of its losers, the vainglorious petty lord Buccmaster. Using an adapted Old English, shorn of Latinate words, that passes from baffling to immersive in about 30 pages, Kingsnorth manages the miraculous task of every very good novel: to make the experience of an alien other understood and deeply felt without sacrificing its wondrous strangeness.

Purity, by Jonathan Franzen (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, September 1)

The writer who needs no introduction wonÔÇÖt benefit from a spot on another list either. But he belongs here, not just by virtue of his mastery of braided narratives that interweave the personal and sociopolitical, but because this time he brings something new. Freedom retreated from the boldest sallies of The Corrections into the middle-class hobbyhorses of its writer, but Purity expands both formally and topically. In the story of Purity TylerÔÇÖs search for her father, abetted by the Julian AssangeÔÇôlike Andreas Wolf, he plumbs grander contradictions while writing funnier humans ÔÇö handling more with a lighter touch.

Negroland, by Margo Jefferson (Pantheon, September 8)

In a moment caught between ObamaÔÇÖs hope and FergusonÔÇÖs despair, a criticÔÇÖs memoir of growing up in ChicagoÔÇÖs black upper class feels like a well-timed appendix. Along with essaysists Ta-Nehisi Coates to Claudia Rankine, Jefferson mines personal experience for political lessons. Yet her eye is more clinical, her voice direct but restrained. That suits her anatomy of a group that, in the mid-century, prided itself on uprightness, superiority, and the conviction that unlike the white rich, it had earned its privilege. Jefferson respects that position but registers its ironies and contradictions.

Did You Ever Have a Family, by Bill Clegg (Scout Press, September 1)

The author who passed from literary agent to crack addict to confessional memoirist (and once again an agent) was himself surprised to have this first novel long-listed for a Booker Prize. But it shouldnÔÇÖt shock anyone whoÔÇÖs read it. Chronicling the complicated aftermath of a mysterious house fire on the eve of a Connecticut wedding, Clegg isnÔÇÖt out to break molds, only hearts. Family melds several grieving voices into a detailed mosaic of a town split between locals and weekenders, a mystery in which the stakes really matter, and a recovery story more original than CleggÔÇÖs own.

Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights, by Salman Rushdie (Random House, September 8)

Critics whoÔÇÖve written off late Rushdie as a coasting, over-tweeting bon vivant might have to rethink their positions; one of the godfathers of hyperrealism has written his strongest novel in years. This clever, pomo-mystical triptych stretches back to Andalusia and forward to a distant utopian future, but the meat of it shows modern New York in the grip of an inter-dimensional battle among jinn that lasts 1,001 nights (see title). Silly? Sometimes, but RushdieÔÇÖs powers of invention and depiction are at least equal to his genre-besotted successors, Lethem and Chabon, at their larky best.