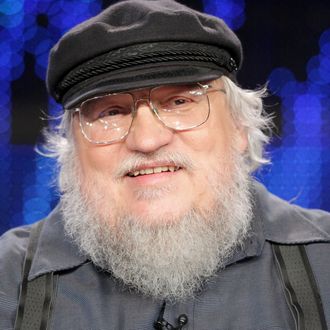

The unwavering success of Game of Thrones continues to be a surreal and stressful ride for George R. R. Martin. The author admitted as much, and more, during a candid, sold-out discussion with NorthwesternÔÇÖs Medill School of Journalism on Wednesday. Martin was present to receive the schoolÔÇÖs Hall of Achievement alumni award, which honors graduates whose careers have had positive impacts on their respective fields, and to give two separate talks to the Northwestern community. (The place is definitely proud of him ÔÇö their athletic department is even honoring him this weekend.)

During his first appearance, which came earlier in the day and was part of a private ceremony, Martin discussed his time in college: He earned a bachelorÔÇÖs degree in journalism there in 1970, and returned for a masterÔÇÖs in the same field the next year. His second, however, was much more Game of ThronesÔÇôcentric, with Martin answering questions on everything from the showÔÇÖs relationship with entertainment journalism and the state of sci-fi today, to his late-in-life celebrity and the end of GoT. Read on for the most interesting highlights from his wide-ranging afternoon Q&A session at Cahn Auditorium:

1. No, he didnÔÇÖt think the show would catch up to him ÔÇö but heÔÇÖs not fazed:

ÔÇ£IÔÇÖve been hearing them come up behind me for years, and the question is, How can I make myself write faster? I think, by now, the answer is, I canÔÇÖt. I write at the pace I write, and what the show is doing is not going to change what the books are,ÔÇØ he said, noting that the only way the TV series influences his writing is in the sense that it ratchets up his stress. ÔÇ£I started writing about these characters and this world in 1991, and we didnÔÇÖt have the first meetings to create the show until 2008, so I got like a 17-year head start!ÔÇØ (To be fair, the workflow timeline is kind of incomparable when you consider the difference between a 1,500-page manuscript and a rapid-fire set of 60-page teleplays.)

2. MartinÔÇÖs career has not been all sunshine and rainbows:

One of the recurring themes Martin discussed Wednesday was the instability of a career in writing, how success or a hot streak can fizzle as quickly, or quicker, than it develops. The author admitted that long before the current success of GoT, he had to rework his career a few times ÔÇö one instance, in particular, was thanks to a show called Doorways, for which a pilot was shot in 1992:

Doorways is interesting. That was one of the greatest crossroads of my career. After I had done The Twilight Zone and Beauty and the Beast, I had moved up the ranks in Hollywood, I had gone from a staff writer to a story editor to an executive story editor to a producer to a co-producer to a supervising producer, and the next step for me was to develop my own show. I wrote pilots for half a dozen shows, none of which ever got picked up, even as a pilot, except Doorways. And Doorways became a pilot for ABC, and at the time, it looked like we were going to get a slot on the schedule. They went so far as to order six backup scripts, and I hired six writers, and we spent half a year developing and polishing and getting ready to shoot the first six episodes when we got the green light.

But we never did.

And then of course, like a year later, a show called Sliders came along, and had basically the same premise, but just done stupid. And that ran for a number of years. And at the time, it was one of the great disappointments of my life. I really thought, and I had good reason to think, that Doorways was going to go, that I was going to be a showrunner with my own series on the air, and had it been a hit, I would have been encouraged to do another show, and another show, and I might have been Dick Wolf or Steven Bochco or something at some point. When Doorways failed to go, and all the other shows I had been developing didnÔÇÖt get to the pilot stage, people suddenly stopped returning my calls. You get a certain amount of strikes out there in Hollywood. YouÔÇÖre as successful as your last project, so that was kind of a bitter disappointment for me.

DonÔÇÖt worry, though ÔÇö he looks back on the show now and realizes that its spiking was a blessing. It was essentially going to be a wannabe-serialized mess of a show, with no dearth of alternate worlds, budget woes, and special-effects shortcomings. ÔÇ£I would have produced an ambitious but severely crippled television show that might not have been the show I really wanted it to be,ÔÇØ he said. ÔÇ£And, failing that, I wrote this Game of Thrones thing, and that worked out pretty well.ÔÇØ

3. HeÔÇÖs aware now that whatever he writes will likely be put on some sort of pedestal ÔÇö but heÔÇÖs being humble and realistic about it:

Martin also had a self-favored darling of a novel, which, similar to Doorways, failed to fully entice prospective buyers. It was about Jack the Ripper running around 1890s New York, with three competing newspaper reporters tracking the killer throughout the city. ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm now at the stage of my career where pretty much anything I care to put down I think IÔÇÖll get some reply, which is a blessing and a curse,ÔÇØ he said. ÔÇ£I try to be aware of that, and I also try to be aware that this too will pass. Game of Thrones right now is the most successful television show in the world, but it wonÔÇÖt always be. Three years from now, some other television show will be the most successful show in the world.ÔÇØ

4. HeÔÇÖs glad heÔÇÖs not Justin Bieber:

With his past career hiccups in mind, he addressed the fact that his true celebrity came to him rather late in life ÔÇö which he sounded at least somewhat grateful for. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs made me have a certain sympathy for the teenage assholes that are running around out there, the Justin Biebers and the Lindsay Lohans ÔÇö no wonder these people are crazy!ÔÇØ he said, eliciting a roomful of laughter. ÔÇ£If this stuff had happened to me ÔÇö if I had written a novel when I was at Northwestern when I was 19 years old and it had sold billions of copies, I wouldnÔÇÖt have been able to handle that at 19. I can barely handle it at 67. ItÔÇÖs surreal.ÔÇØ

5. He pointed out that sci-fi is a lot more depressing now:

When asked about the future of his favorite genres ÔÇö sci-fi, in particular ÔÇö Martin noted one astute observation about the contemporary stories crowding bookshelves now. It seems weÔÇÖre afraid of the world of tomorrow, he said, referencing the fact that sci-fi books in the ÔÇÖ50s and ÔÇÖ60s typically marveled at the possibility of future advancements that would make life easier; whereas, now, such stories like The Hunger Games, Maze Runner, and The Giver spin much more pessimistic, dystopian yarns. ÔÇ£Where does science fiction go from now? Does it go into dystopias? Or is there a new way to constitute this stuff?ÔÇØ he asked, pointing out that writers have seemingly abandoned the older sensibilities of the Robert A. Heinleins of the genre. ÔÇ£I donÔÇÖt know.ÔÇØ

6. As for the future of Game of Thrones, he has a somewhat clearer idea:

Kind of. Although hes more sure of GoTs end, hes obviously still being a little coy. I think you need to have some hope, he said, referencing the manners in which sagas end. We all yearn for happy endings in a sense. Myself, Im attracted to the bittersweet ending. People ask me how Game of Thrones is gonna end, and Im not gonna tell them  but I always say to expect something bittersweet in the end, like [J.R.R. Tolkien]. I think Tolkien did this brilliantly. I didnt understand that when I was a kid  when I read Return of the King. Now, however, he notes that Tolkiens use of allegory to reveal lifes grittier truths (the tragedy of post-war Britain in the late 40s and early 50s, in the case of Lord of the Rings), even in the face of a well-earned victory is brilliant. You cant just fulfill a quest and then pretend life is perfect, he said. Life doesnt work that way.