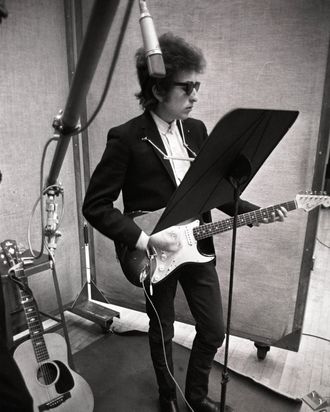

Dylan concerts have never really been intended for hit-seeking crowds (imagine that), as heÔÇÖs fond of reworking his most iconic songs into different styles and tempos. It can be a fascinating thought experiment, hearing what could have been of the ÔÇÿ60s folk and rock canon ÔÇö one that drives interest to a new Dylan box set, The Cutting Edge 1965ÔÇô1966: The Bootleg Series Vol. 12, out this Friday. Over the course of many discs (one comprised of nothing but alternate versions of ÔÇ£Like a Rolling StoneÔÇØ), listeners bear witness to DylanÔÇÖs creative process in the studio during one of the most divisive moments of his career: starting with 1965ÔÇÖs Bringing It All Back Home and culminating with his all-time classic Blonde on Blonde the following year, the period when he first gravitated toward electric sounds and more abstract lyrics.

On a micro level, ÔÇ£Just Like a WomanÔÇØ ÔÇö one of Blonde on BlondeÔÇÖs more pop-leaning waltzes ÔÇö is equally divisive. Naturally, listeners have long debated whom the song is about, as there are lyrics seemingly inspired by different famous women in DylanÔÇÖs life (the ÔÇ£fog, amphetamine, and pearlsÔÇØ line often linked to Edie Sedgwick, ÔÇ£Please donÔÇÖt let on that you knew me when / I was hungry and it was your worldÔÇØ to Joan Baez). Others (though not Shelley DuvallÔÇÖs Annie Hall character) have debated the songÔÇÖs alleged misogyny, a product of its broad (but somewhat scathing) summation of feminine wiles and vulnerability. Both are interesting angles to consider in listening to one of three ÔÇ£Just Like a WomanÔÇØ outtakes (including a Bo DiddleyÔÇôesque version of much interest) that appear on The Cutting Edge 1965ÔÇô1966, one of which Vulture premieres exclusively below.

Here on his first studio take of ÔÇ£Just Like a Woman,ÔÇØ Dylan is even more pointed in his critique of his subject(s), using second-person pronouns from the very first chorus instead of switching from ÔÇ£sheÔÇØ to ÔÇ£youÔÇØ in the last chorus for effect. He repeats the cutting ÔÇ£fake just like a womanÔÇØ line more than once here, too, and throws in lyrics about ÔÇ£how hard she schemesÔÇØ and how he gave her the songÔÇÖs infamous pearls. Musically, however, the song is a little tamer: slowed down, with less prominent percussion and more smooth, soulful electric-guitar melodies in place of the originalÔÇÖs flourishes of finger-picked Spanish guitar. Essentially, Dylan traded some of his lyrical directness for musical oomph in the final, more balanced version. Hearing this shift for yourself, to steal DuvallÔÇÖs line, is transplendent.