Long ago, in the year 1983, a man with a mustache and a woman with mermaid hair made their way to New York City. The woman was scared to pick up the phone because her accent made people shout as if she were deaf. The man, a doctor, smiled brightly even as his colleagues shut him out of the normal rites of passage: no welcome dinner, no slaps on the back.

These are Ramesh and Nisha Shah, the fictional parents of Dev Shah. They’re played by Shoukath and Fatima Ansari, the real parents of the show’s creator, star, and director, Aziz Ansari.

What makes his parents ordinary makes them, in this context, special. The Ansaris are all of our parents, who would probably surprise us if asked to cameo on television with their outsider’s charm, whether through a sweetly stilted monotone (Ma Ansari) or a totally singular sense of humor (Pa Ansari).

That said, when I first watched episode two — titled “Parents” — I couldn’t quite catch my breath. The casting struck me as revolutionary in the best sense, because we really should have seen this revolution coming. Parents as a category make for good watching, and Indian parents are art. Having grown up in a house run by them, in a community defined by them, the link between Indian immigrants’ condition and humor never escaped me. My parents’ lives rested on a precipice. Opportunity to question the wisdom of their choice to emigrate lay at every treacherous corner, when they first tried to buy a house in a new country, send kids to schools unlike their own, ignore thoughtless barbs from naïve neighbors, claim success in offices with no one who looked like them. The fact is, they could have chosen a life with more ceilings and less cognitive dissonance. My mother couldn’t wear pants until she arrived in the U.S.; I wore bathing suits all summer long.

When a leap of faith orients every next step, you learn to make jokes about the unexpected scenery along the way. You can look at your strange American child in her bikini and feel distant and sad and angry. Many Indian parents I know wielded anger like a weapon. Their kids never smoked cigarettes or wore lipstick because the threat of parental fury loomed too large. Others worked by gentler means, using humor, kindness, and the power of example to meet their alien children halfway.

People like to talk about the importance of seeing one’s own self reflected in the stories we tell, on television, in the movies, onstage. I saw my parents in the littlest gestures of the Ansaris. This felt more miraculous than seeing a brown girl in skinny jeans with complicated opinions thrown back at me. I belong to modern America, while immigrant parents live in a secret world only we kids know. Like Ramesh, my dad makes strange jokes enhanced by exaggerated eye movements. “I like Brian,” is precisely the kind of playful insult he might use against me if I let him down somehow, as Dev does in one of the show’s most memorable scenes. Spliced with a flashback to Ramesh’s hard-knock childhood in India, it pans to a future in which his request for tech help is rejected by the son he sacrificed so much to buy a computer for in the first place, all those years ago.

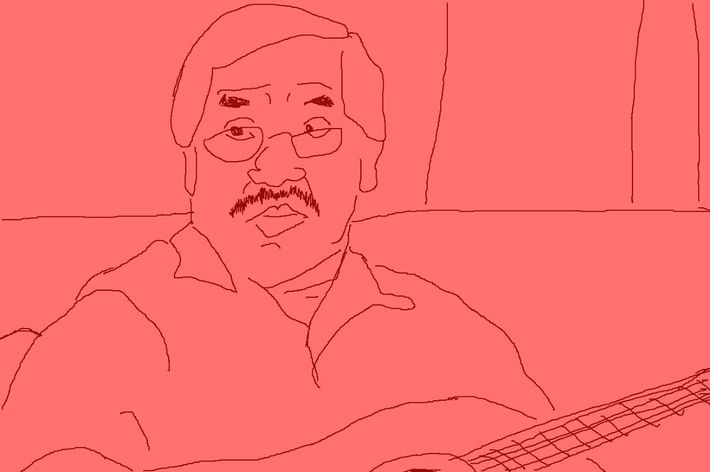

Much is also familiar in the couple’s onscreen chemistry. Like Nisha, one of my mom’s classic moves was to pretend not to find my dad funny. She’d press her lips together after one of his jokes, which were mostly puns or other forms of wordplay, all with remarkably low universal value — Ramesh-style moves in the aim of making absurd non-humor funny simply by virtue of it being said. For an example of an un-joke getting joke treatment and soaring because of the disconnect in “Parents,” see Ramesh’s body language during his guitar solo about not going to Mr. Cho’s Chinese restaurant. It’s inappropriately hammy, and totally works.

Early in the episode, Aziz more or less spells out why he’s given his parents starring roles. Like me in my bikini, he is a warped expression of the freedom his parents left India to find. They could not have foreseen their son in his current form. Whatever one might say about his success, it is not of the stable shape theirs took — the life of a comic actor is practically inverse to the career path of a doctor, which rises steadily as long as it needs to, and plateaus where a doctor chooses. Actors flame and fall until they hit the sky or the ground. As is his way, Aziz states his own discomfort with this generational shift as baldly as anyone can — in a conversation with Kelvin Yu, as Brian. The gist of it could work as a chapter title in the first draft of a social-theory thesis: Man, our parents did so much for us.

But then, they did. There’s something refreshing about just saying the enormity of what happened, just like that. I envy Aziz’s ability to pay homage to his parents in the simplest of ways: by showing them as they are. Ramesh’s guitar solo, for instance, culminates a drawn-out gag so quietly perfect I can’t stop thinking about it, about Nisha’s distaste for Chinese food and Ramesh’s insistence on taking her to try it in any case. The bit bottles the spirit of a solid late-stage arranged marriage. There’s a sibling-esque prodding at each other’s nerves that arguably keeps feeling alive well past the emotional death date for so many love marriages. Nisha eats nothing but rice in the restaurant her husband persists in trying to endear to her. For so many Indian couples who came over in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the men arrived first. They measured the lay of the land, they entered workforces, they tried alcohol and beef and pork. Their wives typically needed prodding and poking and goading and teasing. These women, in turn, provided censure when the men took their explorer persona too seriously. I can’t count the number of times I’ve heard my mom upbraid my dad in the same cadence Nisha uses after Ramesh’s Mr. Cho ballad. She tells him — man, did I see this coming — essentially, to shut up. She’s smiling, though. My mom did, too.

Illustrations by Mallika Rao