An instant message came across the wire just before 1 p.m. today: “I want you to go watch movies with shia the beef.” It was my editor, referring to actor/artist/plagiarist Shia LaBeouf’s abrupt announcement that he had just started screening all of his movies, in reverse chronological order, for free, uninterrupted, at Manhattan’s Angelika Film Center. He’s calling it “#AllMyMovies.” Like the rest of America, I have a fair amount of LaBeouf Fatigue, but my FOMO was stronger than my reluctance, so I hopped in a cab and was there within the hour.

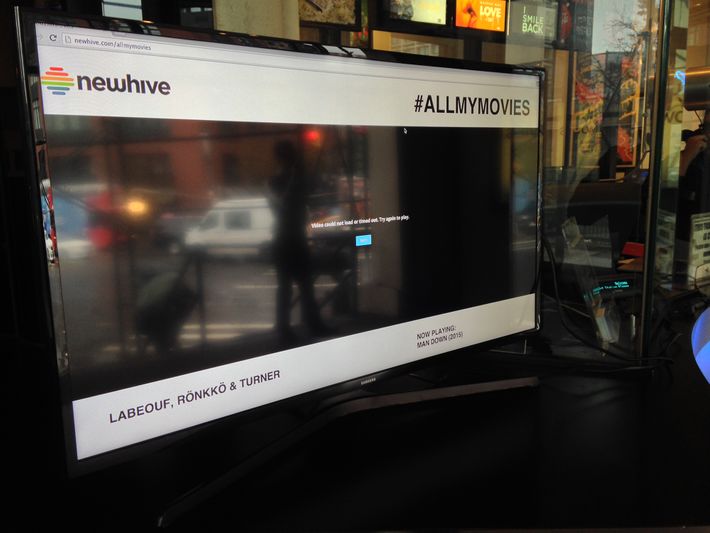

The marathon had only begun around noon, so the building was pretty desolate. The sole indicator that the whole thing was happening was a video screen propped up next to the box-office window, showing the webpage where LaBeouf was livestreaming from a camera pointed directly at his face. The livestream feed appeared to be broken.

There was a smattering of people in the lobby, none of whom seemed to be there for #AllMyMovies. An elderly woman was at the snack counter, interrogating a sleepy employee about whether the theater would ever fix “those horrible, uncomfortable seats.” I asked her if she knew about the marathon. “The what?” she asked. I told her Shia LaBeouf was screening all of his movies at the theater, and that she could go see them for free. “I’m not really sure who that is,” she replied.

A ticket-taker asked me to show him some ID. I asked why. “Gotta make sure you’re over 18 so you can see some of the stuff they’re showing.” Oh right, Nymphomaniac! Another ticket-taker right next to him gave me a ticket from one of those rolls you can buy at a party-supply store, told me very sternly that photography and phone use were strictly forbidden, and pointed me toward a downstairs theater. A pair of ushers stood outside the theater’s door, and one gave me a very thorough scan with a handheld metal detector while the other reiterated his upstairs colleague’s edict about photography. “You got it,” I said, and they let me in.

The room was only large enough to accommodate about 75 people, and there were 22 in the audience. Well, 23 if you count Shia LaBeouf. He was seated on the aisle, midway through the theater, wearing a blank T-shirt, dark pants, and a mildly intimidating beard. A short woman was sitting to his right, but his row was otherwise unoccupied. And no one was looking at him! If you ignored the small camcorder propped on a tripod in the seat in front of him, the whole scene was an entirely normal one for a midweek matinee at the Angelika — right down to the presence of a movie star among a smattering of unimpressed New Yorkers.

By sheer coincidence, I entered just as the second movie in the series started: last year’s David Ayer–helmed World War II drama Fury, in which a bunch of American soldiers ride a tank through Germany in the waning days of the Eastern Front. I first sat behind and to the far right of LaBeouf, but quickly realized I needed a better vantage point to catch glimpses of his reactions. I heaved myself over the back of the seat in front of me, sat at the opposite end of his row, and took out my reporter’s notebook to scribble in the dark.

For the vast majority of the movie’s tediously macho 135 minutes, LaBeouf sat with the kind of emotionless, wide-eyed, laser-focused gaze you might see on a cat that’s eyeing a bird from a window. I kept turning to see if he was doing anything and, with only a few exceptions, he gave me nothing. Sometimes he’d be eating from his medium-sized popcorn bag, but most of the time, he was completely still. The first few times I twisted my head in his direction, I tried to be discreet. I kept thinking of the lessons my high-school physics teacher had taught us about the observer effect: Every time you look, you change the thing you’re looking at. I didn’t want to go from objective reporter to disruptive participant. But after about the fifth glance, I realized he either (a) was choosing to ignore me as part of his performance or (b) didn’t give a shit about me. Even when some douchebag took a flash photo right next to his face and quietly sped out, LaBeouf only looked to the side for a moment, then went back to staring at the screen, unfazed.

He hardly ever showed any emotion, but boy, he loved all the dick jokes. LaBeouf plays a devout Christian who spends most of his minimal screen time quoting scripture to his comrades, so he rarely laughed at any of his own lines, but he couldn’t get enough of ribald fellow-soldiers Michael Peña and Jon Bernthal. For example: During a tank ride, the nervous protagonist sees a German refugee woman and Peña jokes, “She’ll let you fuck her for a chocolate bar.” LaBeouf’s face swelled into a grin, and he let out a hearty (but silent) chuckle. Later on, the soldiers find out the protagonist had sex with a different German woman and start frattily ribbing him for it, and again LaBeouf cracked up. Same thing when Peña talks about yet another German woman, telling everyone, “She looks a little like a whore.”

I got excited when I realized I had to use the bathroom, because it meant I could leave the row and push past LaBeouf, which would allow me to see if he was a stand-up-and-let-the-person-past-you kinda guy or if he was more into remaining seated and swishing his legs to the side. It was the latter! I used the facilities, and as I walked back in, I snapped a picture of the still-quiet scene outside the room, drawing suspicion from a clean-cut, thirty-something man who asked what I was doing. I said I was reporting on the event, assured him I wasn’t using my phone inside the theater, and asked who he was. He was, apparently, with LaBeouf’s management company. I asked how long this had been in the works; he said it had been about a year. I asked how it was all going so far; he said it was great, and that they were expecting to have a crowd this small at this early a point in the marathon. “Oh yeah,” I said, “once you get closer to the end of the work day, I’m sure the crowd will beef up.” He looked at me and started laughing. I told him I genuinely hadn’t meant to make a pun, but he didn’t seem to believe me.

Then it was back to the dull, performance-art grind. By this point, the number of people in the crowd had trickled up to a healthy 45 or so, and people were looking toward LaBeouf a little more often, but there still wasn’t much to see. When his character was violently shot in the movie’s climactic battle, about a half-dozen of us darted our heads toward him, but he just lightly raised his eyebrows in an expression that could have meant Death, man — whaddaya gonna do? or could have meant absolutely nothing.

As soon as the credits began, LaBeouf shot up and half-ran out of the theater. I wriggled out of the row to follow him, but he was nowhere to be found. A handful of people waited around for him to come back, and when he did, one of them walked right up to him, said something, and LaBeouf cocked his head in recognition before going in for a massive bro-hug and swiftly walking back into the theater. I talked to the hug recipient, Josh Flitter, who appeared with LaBeouf in 2005’s The Greatest Game Ever Played when they were both child actors. “Yeah, he came to my 12th birthday party,” Flitter told me. “Haven’t seen him much since then. You lose touch with people, y’know?”

The crowd of attendees was growing and I had to leave so I could file this report, but first, I ran back into the theater to execute a last-ditch gambit for a quick quote. I leaned over to LaBeouf and asked him, “Successful so far?” He made brief eye contact, thought about it, made a cryptic facial expression, and silently nodded his head to the side as though he were saying both “Yeah” and “Who knows?” at the same time. That seems about right.