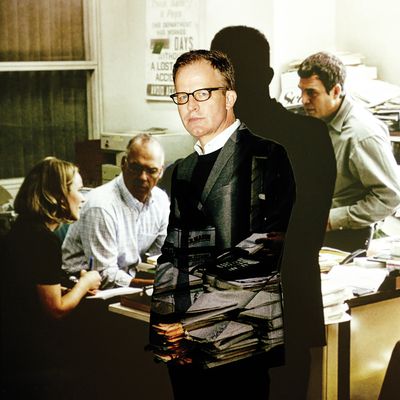

When Tom McCarthy, a preppy, generically handsome white guy, gets stopped on the street, it’s usually by people who think he went to high school with them or perhaps was in their sailing class. You might know his name from the excellent modest-budget adult dramas he’s written and directed: The Station Agent, The Visitor, Win Win, and his latest, Spotlight, which seems a shoo-in for a Best Picture nomination. (We’ll get to his one clunker, 2014’s The Cobbler, later.) He’s also an actor, and if you’ve watched season five of HBO’s The Wire, then you most definitely recognize his face. Likely as one you want to punch. It’s the face of that weasel of a character Scott Templeton, possibly the slimiest, most despicable news reporter in television history.

“I think it’s safe to say that I’m a bad guy for most journalists,” says McCarthy. We’re on a brisk walk along the Hudson River from Soho, near where he lives with his poet wife and their two young daughters, to the Jane Hotel, one of his favorite lunch spots. His Wire character wasn’t just a bad reporter; he’s an unethical metro-desk striver whose fabrication of stories about a serial killer targeting homeless men leads to a murder and the demotion of two of his colleagues. McCarthy tells me about how he was once standing on Houston Street when the driver of a Verizon van leaned out of his window and shouted, “ ‘You’re a bad man!’ And I look over and he’s like, ‘That’s right. You’re a baaaad man!’ ” says McCarthy. “And everyone’s looking at me and they’re like, ‘What did he do to the Verizon guy?’ ”

Now, the man who played Scott Templeton has co-written and directed what critics are calling the most valorizing movie about journalism since All the President’s Men.

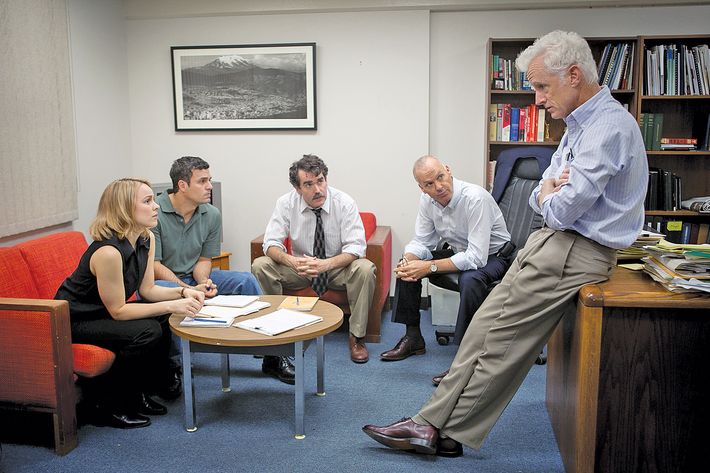

Spotlight is named after the team at the Boston Globe that, in 2001, launched the investigation that exposed decades of child molestation at the hands of priests and its systematic cover-up within the Catholic Church. It is a nail-biter of a procedural, with a ridiculous ensemble cast (Michael Keaton, Mark Ruffalo, Rachel McAdams, Liev Schreiber) and a deep respect for the hard work of, and urgent need for, local, shoe-leather reporting. And yet when McCarthy entered the Globe’s newsroom, where much of the movie was filmed, he heard a few sneering shouts of “Templeton!” Even sitting down with the real Spotlight reporters felt like an inquisition. “They came right at me!” says McCarthy. “ ‘Why are you telling this story?’ ”

It’s a question McCarthy doesn’t quite know how to answer. As a director, he’s beloved for a certain whimsicality, and none of his prior movies has been based on a true story. His first feature, 2003’s The Station Agent, is a meditation on loneliness that introduced his friend Peter Dinklage as a leading man. He and Dinklage had met doing downtown theater, and the movie is imbued with their mutual affection. “Tom is responsible for my career as an actor,” Dinklage writes by email from the Game of Thrones set. “We made that movie with friends for no money and it’s incredible that people from all over still tell me how much they loved The Station Master. (*****joke – people always get the title wrong. can you please leave the wrong title ??)”

McCarthy wasn’t struggling as an actor when he started writing and directing, but he was eager to scratch the itch for storytelling that he’d developed around the dinner table as one of five kids in a big Irish Catholic family. “Tom was an actor who worked all the time — TV, film, Broadway,” says Amy Ryan, who co-starred in McCarthy’s 2011 oddball high-school-wrestling drama Win Win, “but he is restless. If I have two months off, I’m psyched. Tom is like, ‘Oh my God, two months off? I better write a film.’ ”

He was in the middle of editing Win Win when Spotlight producers Nicole Rocklin and Blye Faust began to pursue him for their potentially bone-dry story of reporters reporting. “They felt this story needed heart and empathy,” says McCarthy, who thought he could at least nail the latter. He’d also developed a strong interest in journalism from his time on The Wire, hanging out with the show’s creator, David Simon, who’d reported for the Baltimore Sun for 13 years before moving to TV. While we walk, McCarthy opens his satchel to reveal a copy of the New York Times. He reads it in print every morning, along with the iPad versions of the Washington Post and, of course, the Boston Globe, to which he is a proud subscriber: “I paid my $1.99 or whatever it was!”

To write the screenplay, McCarthy needed to become a kind of journalist himself. There is no Spotlight tell-all or memoir; Rocklin and Faust only controlled the reporters’ and editors’ life rights. McCarthy told them to send him whatever information they had, and, he says, “The next day, seven volumes of reporting clips are in my office. It was overwhelming.”

The workload was so huge that McCarthy enlisted a co-writer, Josh Singer, who was finishing up another journalism-centric movie, the WikiLeaks dramatization The Fifth Estate. In August 2012, the two took a train to Boston and began conducting interviews. “We kept widening our net in terms of who to talk to,” says McCarthy. “Lawyers, former reporters, publishers, editors, survivors.” A time line emerged, as did conflicting stories of what had happened. “It was basically an investigation of their investigation,” says McCarthy. He and Singer went so deep they even uncovered things the Spotlight team had overlooked, such as a Globe article about 20 pedophile priests written years earlier but apparently never followed up on; the devastating scene in the movie when the reporters confront that oversight is a mirror of what happened when Singer and McCarthy brought the piece to their attention.

Mostly, though, the movie is less about big moments than the quotidian craft of newspaper reporting — knocking on doors, staking out the courthouse. “I sometimes wonder if the general public has a sense of how dire the state of journalism is and how important it is,” says McCarthy. “I think we’ve lost track of that a little bit with citizen journalists and everyone having a camera and a tweet.”

McCarthy says that if Spotlight has a central theme beyond the value of dogged journalism, “it’s societal deference and complicity.” How did this abuse go on for so long? What was it about insular Boston that made digging into a story like this so difficult? John Slattery, who plays a Globe editor, grew up in the city and says, “You’d be hard pressed to find someone that hadn’t heard a rumbling about something swept under the carpet. I went to an all-boys Catholic high school, and I certainly heard things.”

McCarthy is no longer a practicing Catholic but was an altar boy in New Provincetown, New Jersey. The first thing he did upon deciding to make the movie was to talk it through with his devout parents. “We have a lot of family in Massachusetts,” he says. “So I was like, ‘You’re gonna hear about it.’ And they did.” A lot of what they heard, says McCarthy, was, “ ‘Why are we going to dig this up again?’ Which is understandable but misguided — it’s still very much an important issue.”

Making a movie like Spotlight, an adult drama about reporters doing a retroactive investigation of pedophile priests, isn’t easy. Though it’s not an expensive movie, its $20 million budget was still twice that of the most expensive of McCarthy’s previous films. Plenty of major studios passed on the project, and he says funding fell through three times. While some directors take the one-for-me, one-for-them approach of balancing passion projects with more commercially viable fare, McCarthy has managed to avoid those compromises. “I do the five-for-me approach!” he says, laughing. “I don’t know if I have figured it out, but I have always been able to tell exactly the stories I’ve wanted to tell.”

It helps that he has a couple side careers to pay the bills. He does a good deal of silent rewriting and polishing on studio scripts, and also worked on the story line for Pixar’s Up. He was the bland, cheating husband in Meet the Parents and Little Fockers and had a bit part alongside buddies Dinklage and Adam Sandler in this past summer’s Pixels, which Rachel McAdams tells me he shot while making Spotlight. “He skipped out of work one day to play a robot,” she says. “That was so quintessentially Tom.” He also was one of the first of many directors attached to the pilot for Game of Thrones before HBO retooled the whole thing.

Spotlight, though, will likely move him into another writing-directing tier. Which, given its immediate predecessor in the McCarthy corpus, makes it somewhat of a surprise: The Cobbler got some of the worst reviews of 2014 following its debut at the Toronto International Film Festival and was buried as a VOD release in March of this year. The film stars Sandler as a Lower East Side cobbler who discovers a magical stitching machine passed down by his Jewish ancestors that allows him to physically transform into his clients — a hoodlum, a drag queen — by walking in their shoes. “We knew what we were doing with The Cobbler,” says McCarthy. “It’s just how people responded to it was different than we figured.”

McCarthy was deep into preproduction for Spotlight when a director friend who’d been at The Cobbler’s first Toronto industry screening called him to warn about the likely bad reviews. “He was like, ‘Get ready,’ ” says McCarthy. “I didn’t anticipate that.” Overall, McCarthy says he found the experience of having his movie panned liberating. “It’s painful,” he says. “You feel it, but I love that movie. If you have four children and suddenly one’s wacky, you go, ‘Hey, he’s wacky, but I love the kid.’ ”

McCarthy looks at his phone. He’s got one of many “tastemaker” screenings for Spotlight tonight and wants to head uptown to check out the theater’s sound system. He finishes by telling me about his favorite screening of the movie so far, at Toronto this year, when he brought the actual Spotlight reporters out to a standing ovation. “It was neat to see them receive that attention,” he says. “Although I’d never seen more uncomfortable people” — he mimics them grimacing — “ ‘Do we bow? Do we raise our hands?’ ” It reminded him of the debate they had over how to end the movie. Someone asked McCarthy why he didn’t throw in a title card saying the reporters had won the Pulitzer Prize. “I put it to the reporters, and they said no. They said, ‘That’s not why we did it. We did it for the facts that you represented there, and those are the facts that we’re most proud of.’ ” What mattered, in the end, was the work.

*This article appears in the November 2, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.