Each month, Boris Kachka offers nonfiction and fiction book recommendations. You should read as many of them as possible.

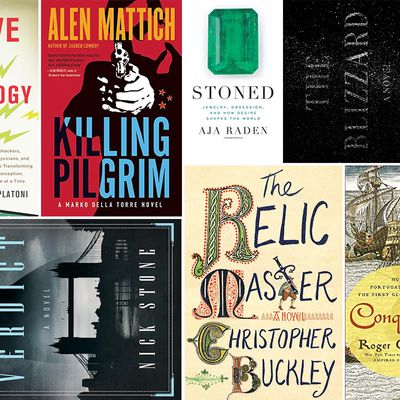

Conquerors: How Portugal Seized the Indian Ocean and Forged the First Global Empire, by Roger Crowley (Random House, Dec. 1)

A far-flung territory ruled by greedy zealots sends soldiers abroad armed with deadly weapons, massive misconceptions, and a burning hatred for rival religions. Somewhere between a high-seas adventure and a revisionist history of the Portuguese Empire as terrorist enterprise, Conquerors focuses on the several decades around 1500 when Vasco de Gama and others sailed and slashed their way to Kerala, transforming their country from EuropeÔÇÖs backwater into, briefly, its greatest power. ThereÔÇÖs more action (and blood) than context, but the stage is set for the Colonial era and its ramifications, all the way to todayÔÇÖs murderous fanatics.

Stoned: Jewelry, Obsession, and How Desire Shapes the World, by Aja Raden (Ecco, December 1)

Raden, both a historian and an actual jeweler, is unusually qualified to embark on this beaded necklace of anecdotes and ruminations, which, more than many single-topic histories, earns its outsize ÔÇ£changed the planetÔÇØ claims. From the sale of Manhattan to the French Revolution and the first wristwatch, gems have the singular quality of being able to move mountains, spark inventions, and exploit millions while being intrinsically worthless. Yet unlike, say, credit-default swaps, theyÔÇÖre irrefutably solid and real (if not necessarily forever).

The Blizzard, by Vladimir Sorokin, translated by Jamey Gambrell (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Dec. 1)

YouÔÇÖd be tempted to call this The Master and Margarita and Zombies, but SorokinÔÇÖs brand of fantasy-satire transcends superficial pastiche. Whether set in the 20th century (the Ice trilogy) or some chillingly familiar New New Russia (Day of the Oprichnik), his hallucinatory novels are politically resonant and startlingly original. The Blizzard goes somewhere new, to a 19th-century Tsarist snowscape. Dr. Platon Ilich and his un-trusty guide Crouper race out into a fearsome storm to cure a village of incipient zombies, bringing to mind BeckettÔÇÖs tramps, albeit with funnier bickering and trippier encounters (a tiny husband, a lewd giant snowman, Kazakhs).

The Relic Master, by Christopher Buckley (Simon & Schuster, Dec. 8)

Having quit Washington satire because ÔÇ£American politics have reached the point of being self-satirized,ÔÇØ the arch humorist tilts his latest lance at the high corruption of the Holy Roman Empire just before the Reformation. Sixteenth-century hustler Dismas traffics in holy relics (roughly 99 to 100 percent of them fake) on behalf of two competing aristocratic clients. After one of them catches him in an underhanded scheme, Dismas and his buddy Albrecht D├╝rer (the painter) are induced to try and steal the shroud of Turin; OceanÔÇÖs-style capers and Spamalot slapstick ensue.

The Verdict, by Nick Stone (Pegasus, Dec. 15)

WeÔÇÖll never live in a world without enough thrillers, but those that find great drama in legal procedure are a little harder to come by. A British-Haitian writer on sabbatical from more gruesome fare (the Voodoo-infused Max Mingus trilogy), Stone intertwines the personal and procedural, the past and the present with a facility that has English critics invoking the holy name of Grisham. It begins when foundering legal clerk Terry Flynt finally lands a big case, only to find himself defending against murder charges a millionaire and ex-friend who betrayed him years ago.

We Have the Technology: How Biohackers, Foodies, Physicians, and Scientists Are Transforming Human Perception, One Sense at a Time, by Kara Platoni (Basic, Dec. 8)

Eschewing both the glib hyperbole of techno-futurists and the finger-wagging of neo-Luddites, Platoni takes her notebook on a whistle-stop tour of sensory pioneers: AI developers, VR engineers, pain analysts, flavor enhancers, and even a few people who really are making the world a better place.┬á Her focus on the senses raises smart questions about the pliable boundaries of human perception and the very real limits of technology ÔÇö at least in primitive 2015.

Killing Pilgrim, by Alen Mattich (House of Anansi Press, Dec. 16)

The fatalistic humor of Eastern Europe meets the hard-boiled style in MattichÔÇÖs second Marko Della Torre novel. Its shady hero, sidelined from the Yugoslav secret police on the eve of civil war, is gang-pressed into chasing the assassin of a Swedish prime minister (an actual unsolved murder). Mattich, a financial columnist, easily inhabits both the Alan Furst historical-spy tradition and the culture of ÔÇÿ90s Zagreb. We know today what became of the Balkans, but the mystery of MarkoÔÇÖs manipulators persists (at least until book three comes out next May).