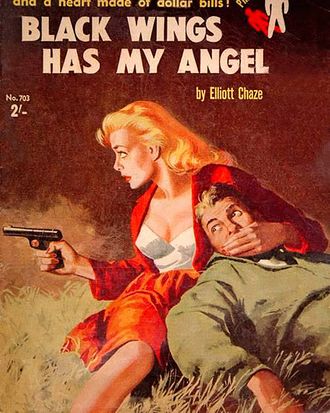

Gold Medal Books emerged in 1950 as a publisher of paperback originals that cost 35 cents and featured deliciously trashy illustrated covers and titles like Meanwhile Back at the Morgue, Make My Coffin Strong, Let Them Eat Bullets, Death Takes the Bus, and One Monday We Killed Them All. It was still the golden age of pulp fiction in America, but Gold MedalÔÇÖs enormous success would be among the forces that started to put the pulp magazines out of business. These books arenÔÇÖt much read any more, and, of course, literary quality wasnÔÇÖt the main criterion for publication, but on the evidence of Black Wings Has My Angel, a flawless 1953 heist novel by Elliott Chaze reprinted this month by New York Review Classics, it wasnÔÇÖt disqualifying either. On a technical level, it is possible to write a perfect crime novel. You might say Black Wings Has My Angel is beyond perfection.

Chaze was a newspaperman who worked as a reporter for the Associated Press in New Orleans, and later as a city editor and columnist for the Hattiesburg American in Mississippi. He was in the army during the Second World War and participated in the occupation of Japan, which provided the setting for his first novel, The Stainless Steel Kimono (1947). He wrote nine novels in total before his death in 1990, as well as short stories, some of which featured a crime-solving newspaperman named Kiel St. James. He landed a single story in The New Yorker in 1947, ÔÇ£Swordsman,ÔÇØ a comical sketch about a G.I. in Japan who acquires an antique sword and then bends it out of shape trying to kill a mouse in his barracks. But, as Barry Gifford writes in his introduction to the new edition, ÔÇ£nothing else Chaze wrote came anywhere close to what he had accomplished on all levels in Black Wings.ÔÇØ

I take Timothy Sunblade, the narrator of Black Wings, to be reliable ÔÇö which is to say I believe that he kills the people he says he kills, and that those shot by somebody else, or who slip and fall and never get up, die the way he says they do. Tim isnÔÇÖt his real name. HeÔÇÖs an escaped convict, a car thief (ÔÇ£You donÔÇÖt know the meaning of freedom until youÔÇÖve been locked up a long timeÔÇØ), a war veteran who suffered a head wound, and a college graduate who had his nose rubbed in his humble origins by the snobs at Washington and Lee ÔÇö ÔÇ£that splendid woman-starved nest of culture where students address one another as ÔÇÿgentleman,ÔÇÖ where freshmen wear nauseatingly cute beanie caps, where no one walks on the hallowed grass, and everyone is so sporting it hurts.ÔÇØ (His take on Washington and Lee can stand in for his attitude to the whole middle-class world.)

At the novelÔÇÖs start, heÔÇÖs just finished a stint on an oil rig in the Atchafalaya┬áRiver. He sleeps with a prostitute named Virginia whoÔÇÖs more sophisticated than most heÔÇÖs met in that part of Louisiana and turns out to be on the lam as well, from trouble in New York City. A lot of the novelÔÇÖs slangy lyricism comes when Tim is looking at her. She joins him when he sets out west in a blue Packard, and soon the novel begins its cycle of halfhearted double-crosses between the pair. Tim has put 17 $100 bills in a girdle and stashed it in the glove compartment, but when he tries to ditch Virginia at gas station, it turns out sheÔÇÖs wearing the girdle and has already driven off with a man passing by in a Jaguar. On reuniting, they beat each other up, and have to camp on a mountainside until their faces heal: ÔÇ£You generally notice the face of a person whoÔÇÖs been in a fight. Scatter a few lumps on it and you remember all the rest of it.ÔÇØ ItÔÇÖs a fairly Edenic sojourn, and the novel unfolds from here as the sort of love story in which either lover might turn in or murder the other at any moment until its last desperate pages.

The heist at the center of Black Wings is a fairly simple one, and it comes off without a hitch ÔÇö Tim and VirginiaÔÇÖs later undoings will come by other means, mostly as a result of their own fears and feelings of guilt. They pose as newlyweds in a working-class Denver neighborhood, and Tim takes a job as a power-shear operator and stakes out the comings and goings of a local bankÔÇÖs armored car. The novelÔÇÖs most brutal scene, in which his foreman loses three fingers to the hydraulic blade, has nothing to do with the crime. The heist has one casualty, a guard whom Tim stabs to death; they leave his body in the back of the armored car, load it onto a trailer, and dump the trailer down an abandoned mine shaft. Their getaway is clean, the haul is a little short of 200 grand. These arenÔÇÖt spoilers. We know from early on that Tim is on death row, though not necessarily for this crime. The confession weÔÇÖre reading isnÔÇÖt without an element of boastfulness. But any pride he feels is darkened by the thought of whatÔÇÖs at the bottom of the hole in Colorado.

Like many a killer in 20th-century noir, Tim is also possessed of a strong morality, basically of a small-town American sort. It comes to the fore when he and Virginia go to New Orleans to spend a bit of the take. They fall in with a decadent crowd of rich 20-somethings, particularly a pair named Eddie and Lorlee:

They all had money to burn, or if they didnÔÇÖt, managed to give that impression, and they laughed about everything. I remember they made jokes about such things as incest and sodomy, and their idea of a big night was to taxi down in the French Quarter and giggle at the queers who put on a floor show down there. IÔÇÖd never thought being rich was anything like that, and still didnÔÇÖt believe it had to be, or else there wouldnÔÇÖt have been the steadfast desire to hang onto my own pile. They worked so hard at being individuals. Eddie wore a green canvas rainhat everywhere he went, even with formal clothes, and he looked like an exhausted cat peering out from under a collard leaf. Loralee did it with bracelets, pounds of them, which dangled and jangled, and with dresses that left her suntanned breasts very much on display. Both she and Eddie were married to somebody or other but, despite the strings of parties, I never saw her husband with her but once and I never saw EddieÔÇÖs wife at all. The married couples swapped around and played grabby in dark corners and all in all it was enough to make you want to stick your finger down your throat. If youÔÇÖre going to be married, really married under the law, you have no business rolling around that way with all comers. Coming from me that must be hard to swallow, but itÔÇÖs the way I felt. IÔÇÖd rather kill a man I donÔÇÖt know and who never did anything to me than have my own children know I slept all over town just for the exercise of it. Virginia, of course, took to it like a duck takes to water. ┬á

As Gifford notes, Chaze was a disciple of Hemingway; what he added to the equation was the flare that gives you that ÔÇ£exhausted catÔÇØ under the collard green. ItÔÇÖs TimÔÇÖs disgust with this scene that puts him and Virginia into the novelÔÇÖs final spirals. They stick with each other when everyoneÔÇÖs against them, knowing that neither of them is really fit for the straight and narrow. When the surprises arrive, Chaze makes no false moves, and none of the plotÔÇÖs mechanics creak. ThereÔÇÖs a shoot-out, cigar-involved police brutality, and a jailbreak. Coming to the book 60 years after it first appeared, youÔÇÖll find yourself wondering why it never got made into a movie. Chaze sold the rights to the French director Jean-Pierre Mocky, whose 1990 adaptation Gifford calls ÔÇ£not very good.ÔÇØ Gifford has for some years been working on a new screenplay with the producer Christopher Peditto. Tom Hiddleston and Anna Paquin were at one point onboard, but the production was suspended after Paquin gave birth to twins in the fall of 2012. For now the novel will have to suffice.