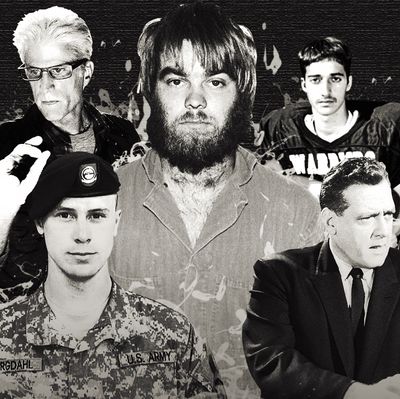

Anyone who tuned in to NetflixÔÇÖs┬áMaking a Murderer, HBOÔÇÖs┬áThe Jinx,┬áor NPRÔÇÖs┬áSerial┬ápodcast probably indulged a fantasy that, had they sat on any of those juries, fair verdicts would have been meted out. The maddening reality, however ÔÇö and part of whatÔÇÖs made all the above mini-series so addictive ÔÇö is that our indignationÔÇÖs been collectively stoked by an overwhelming presentation of evidence and testimony that could have only been accrued in the years following each caseÔÇÖs respective trials.

To be sure, all three works are exemplary of investigative storytelling at its finest, rousing us from social-media self-involvement with the kind of probing journalism that was once the province of newspapers and network-TV expos├®s. And as transmitted via streaming television and iTunes downloads, the new wave of true-crime narrative feels tantalizingly two-way, as if it were a virtual invitation from filmmakers and producers to help demystify the criminal-justice system. But does that suggest that, postÔÇôSteven Avery, Brendan Dassey, Robert Durst, and Adnan Masud Syed ÔÇö the aforementioned broadcastsÔÇÖ polarizing subjects ÔÇö attorneys will suddenly be selecting from a more cynical jury pool? Or are such questions just a requisite rehashing of the mid-2000sÔÇÖ┬áÔÇ£CSI effectÔÇØ┬ádebate (or even its forebear, the so-called┬áÔÇ£Perry Mason┬ásyndromeÔÇØ), a study that considered whether CBSÔÇÖs hit procedural was directly linked to an uptick in jurors insisting on examining substantial forensic evidence before delivering a conviction? (As one researcher writes of the supposed┬áCSI┬áeffect, ÔÇ£I once┬áheard a juror complain that the prosecution had not done a thorough job because ÔÇÿthey didnÔÇÖt even dust the lawn for fingerprints.ÔÇÖÔÇØ)

ÔÇ£These [docu-]series are, at least on the face of them, less an indictment of forensic science and more of the legal system,ÔÇØ points out Melissa Littlefield, associate professor of English at the University of Illinois and author of journal article┬áÔÇ£Historicizing the CSI Effect(s),ÔÇØ as a means to distinguish┬áThe Jinx┬áand contemporaries from their scripted predecessors. ÔÇ£We wouldnÔÇÖt be talking about the┬áCSI┬áeffect. WeÔÇÖd be talking about some other kind of effect thatÔÇÖs producing a desire to do a kind of armchair retrial in the public eye.ÔÇØ

And while itÔÇÖs a bit premature to gauge the appreciable implications of┬áSerial┬áand its kin on trial juries, the legal community has certainly taken notice and anticipates subtle, tactical changes in the courtroom.┬áÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs certainly something the defense will try to dance around,ÔÇØ affirms criminal-defense lawyer Joel Isaacson, whose clients have included convicted sibling murderers┬áLyle and Erik Menendez. ÔÇ£I donÔÇÖt know if it would be proper to talk to a jury and say, ÔÇÿNow, you know how many people have been released off of death row because they were innocent,ÔÇÖ but you certainly would like to keep it in the forefront of the jurorsÔÇÖ minds and try to get them to require clear, confident, convincing evidence beyond a reasonable doubt.ÔÇØ

Though if you ask professional jury consultants, someone plucked fresh from devouring┬áMaking a Murderer┬ámight not even make it past their first day of civic duty. ÔÇ£You would want to have the attorney ask: ÔÇÿHow long did you watch it? With whom might you have had conversations about what you saw? Have you done anything in furtherance of your feelings about the show? For instance, some sort of social-media post,ÔÇÖÔÇØ advises trial consultant Jo-Ellan Dimitrius, whoÔÇÖs helped select juries for clients representing both plaintiffs and defendants, notably including O.J. SimpsonÔÇÖs 1994 defense team. ÔÇ£By gaining that information, youÔÇÖre going to get a good mind-set of [whether] they were biased in favor of Mr. Avery and against the prosecution or police.ÔÇØ Moreover, she projects that potential jurorsÔÇÖ familiarity with┬áMaking a Murderer┬áin particular ÔÇ£will be a significant question on criminal cases from here on out. We used to ask those questions about┬áCSI┬ábecause it was pretty predictive of someone who was a defense-prone juror.ÔÇØ

But as previous empirical and anecdotal research into the┬áCSI┬áeffect would suggest, a culturally savvy jury wonÔÇÖt necessarily be compelled further toward or against incrimination. In 2008, Donald E. Shelton, a former Michigan Circuit Judge and current University of Michigan-Dearborn director of criminal-justice studies, published a study titled ÔÇ£The ÔÇÿCSI┬áEffectÔÇÖ: Does It Really Exist?ÔÇØ He and two colleagues surveyed 1,000 selected pretrial jurors on ÔÇ£their expectations and demands for scientific evidence and their television-watching habits.ÔÇØ Per the study, its results bore out that, ÔÇ£Although┬áCSI┬áviewers had higher expectations for scientific evidence than non-CSI┬áviewers, these expectations had little, if any, bearing on the respondentsÔÇÖ propensity to convict.ÔÇØ

A data-driven 2005 study on the subject published by University of North Carolina Greensboro associate professor of media studies Kimberlianne Podlas, titled ÔÇ£The CSI Effect: Exposing the Media Myth,ÔÇØ takes that skepticism a step further. PodlasÔÇÖs research, which coupled surveys similar to SheltonÔÇÖs with application of theories on media and the law, not only ÔÇ£strongly denies the existence of any negative effect of┬áCSI┬áon ÔÇÿnot guiltyÔÇÖ verdicts,ÔÇØ but contests that it could just as readily complicate the defenseÔÇÖs claims of innocence as tax the plaintiffÔÇÖs burden of proof. In short, its impact is arguably negligible.

In the decade since PodlasÔÇÖs report,┬áMaking a Murderer┬áand like-minded docuseries havenÔÇÖt necessarily altered her point of view. Though she does concede that the placebo of constantly reinforcing┬áCSI-effect-derived thinking can lead to genuine judiciary paranoia.

ÔÇ£I think thereÔÇÖs an effect of believing in the effect,ÔÇØ Podlas explains. ÔÇ£If judges, prosecutors, and law enforcement think there is some kind of effect going on ÔÇö whether theyÔÇÖre correct or not ÔÇö then that will necessarily┬áinfluence their behaviors in the courtroom, in choosing cases, in deciding when theyÔÇÖre going to have splashy conferences, what kind of experts they might choose.┬áWith regards to the public and jurors, if youÔÇÖre used to the story of, ÔÇÿThis is how we go about catching the bad guy,ÔÇÖ or, ÔÇÿThis is what you should expect will be revealed in a trial,ÔÇÖ then when someone is presenting facts or a theory of a case, if what theyÔÇÖre saying matches the dominant cultural story, people are more prone to believe it.ÔÇØ

When it comes to┬áSerial,┬áThe Jinx,┬áor┬áMaking a Murderer,┬áitÔÇÖs more likely they┬ámerely confirmed viewersÔÇÖ skeptical tendencies rather than awakened them. After all, jurors ÔÇö like all people ÔÇö are encoded with a lifetime of stimuli that have shaped their worldview, minimizing the likelihood that recently ingested media would directly radicalize their biases. So by the time a trialÔÇÖs commenced, even the most cynical juries will likely allow a measure of deference to the ensuing process.

As Simon A. Cole, a┬ánoted┬áCSI┬áeffect skeptic┬áand professor of Criminology, Law, and Society at University of California, Irvine, puts it, ÔÇ£Everything we know about juries seems to suggest that, while being on a jury is often unpleasant, they take it very seriously and are making serious decisions about whether to find someone guilty or not guilty in a criminal case. ItÔÇÖs a hard argument to make that theyÔÇÖre going to make a different decision based on whatÔÇÖs gotten in their head from television.ÔÇØ

When it comes down to it, the most obvious and immediate impression these docuseries are making is on the specific cases theyÔÇÖve given cause to revisit. And to those whose lives have been altered by the verdicts handed down to Steven Avery, Brendan Dassey, Robert Durst, and Adnan Masud Syed, that impact is unimaginably significant. As for whether it will influence a generation of sophisticated future jurors who can preempt the need for a┬áSerial┬áor┬áJinx┬áto even manifest, thatÔÇÖs perhaps idealistic. But as UNC GreensboroÔÇÖs Podlas acknowledges of the very correlations sheÔÇÖs sought to disprove, ÔÇ£If these kinds of theories can get people thinking about how the legal system works, then so much the better.ÔÇØ