Each month, Boris Kachka offers nonfiction and fiction book recommendations. You should read as many of them as possible.

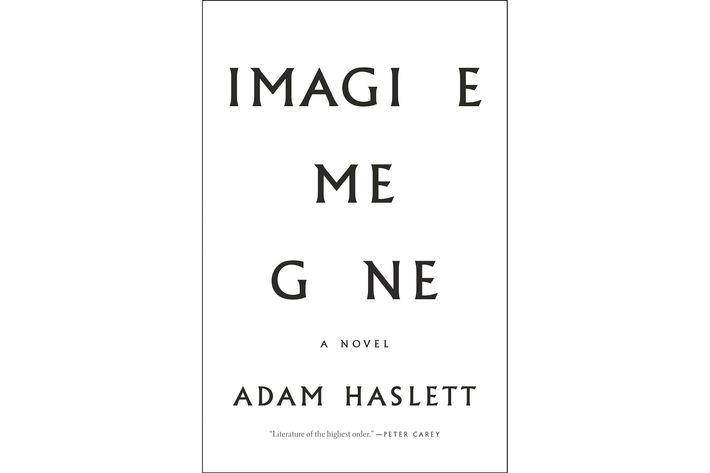

Imagine Me Gone, by Adam Haslett (Little, Brown, May 3)

HaslettÔÇÖs story collection, You Are Not a Stranger Here, revolved around the communal aftermath of mental illness; it made you wonder if its debut author had already dug as deeply as he could. He hadnÔÇÖt. His third book,┬áImagine Me Gone, finds in one familyÔÇÖs tragedies an even smarter and more polyphonic treatment of the subject. Gifted and unstable Michael is the novelÔÇÖs focus, but each of five family members gets to tell a different version of the story. Haslett is that rare writer whose art can console without ceasing to be art.

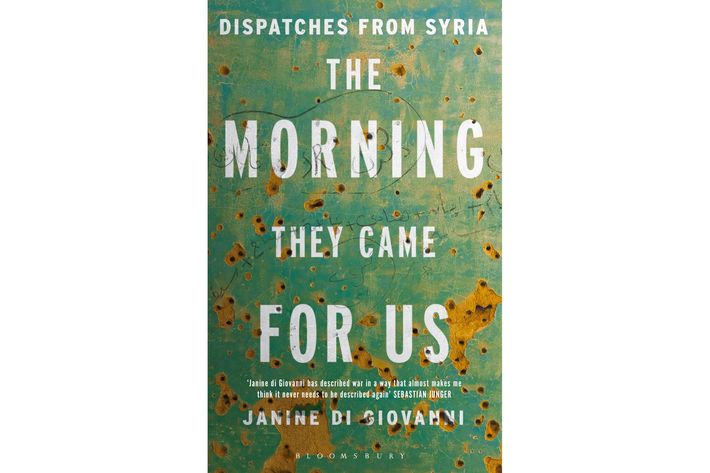

The Morning They Came for Us: Dispatches from Syria, by Janine di Giovanni (Liveright, May 3)

In a rather short book stuffed with too many graphic accounts of torture, rape, and killing (can there ever not be too many?), the longtime war correspondentÔÇÖs boldest inclusion is her own traumatic attachment to such places as Syria in 2012, where she reports on the governmentÔÇÖs brutality and the rise of ISIS, its competitors in savagery. Scarred by the Bosnian conflict, Giovanni nonetheless came back to war; here she uses her hurt to invoke our empathy, even from the safe and sometimes numbing remove of the printed page.

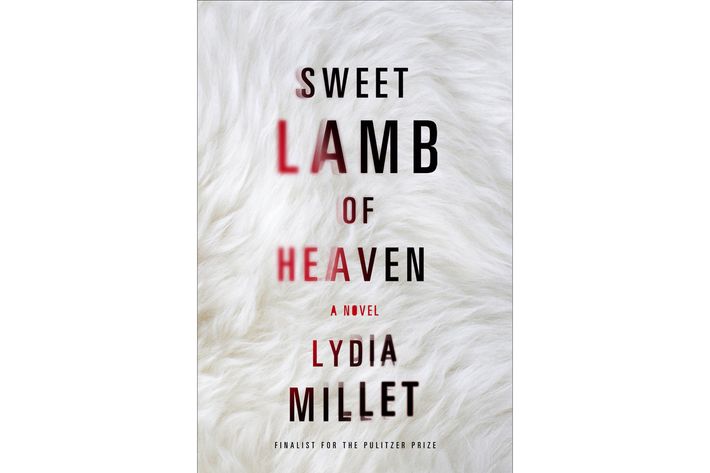

Sweet Lamb of Heaven, by Lydia Millet (W.W. Norton, May 3)

If MilletÔÇÖs title and premise ÔÇö woman hears voices from her baby, hides out from her estranged, psycho politician-husband ÔÇö primes you to expect genre conformity, prepare to be surprised by more than plot twists. The woman, Anna, is too dry and passive to fit the mold of wifely revenge; her husband, Ned ÔÇö picture Ted Cruz if he had charisma and actually fit a serial killerÔÇÖs profile ÔÇö is too specific to be anyoneÔÇÖs stereotype. And as Anna and other voice-hearers explore the collective unconscious of their hallucinations, the Pulitzer finalistÔÇÖs philosophical fireworks add layers of energy and mystery.

The Politicians and the Egalitarians, by Sean Wilentz (W.W. Norton, May 16)

The 2016 Democratic primary never comes up in the Princeton historianÔÇÖs forceful defense of both partisanship and Establishment liberalism, but the essential choice ÔÇö between a prophet of purity and a steward of incremental change ÔÇö is the main event. Before there were Bernie Bros and Bloomberg technocrats, there was George Washington, arguing against parties in order to buck up his own; the angry populist Andrew Jackson; the overreaching Reconstructionists; and Howard ZinnÔÇÖs unsung heroes. Wilentz thinks too much credit is given to the activists and too little to the skillful manipulators, Lincoln included, who turned their selfish ambitions toward noble ends.

Zero K, by Don DeLillo (Scribner, May 10)

To the delight of fans and even mild skeptics of post-Underworld DeLillo, this excursion into sci-fi cryogenics is deep-chilled in his signature style. Still heavier on concepts than characters, Zero K isnÔÇÖt a departure, but it is an advance. DeLillo charts the wildest dreams and nightmares of futurism but mainly the ultimate singularity: immortality. Financier Ross Lockhart and his terminally ill wife make preparations to depart from this world, perhaps only temporarily, via a freeze facility in central Asia. The billionaire plans to leave it all to his wayward son, but Jeff, our skeptical Virgil, has other dreams.

Sweetbitter, by Stephanie Danler (Knopf, May 24)

Yet another thumbsucker about the wising up of a big-city arriviste? DanlerÔÇÖs debut is that, and trails other baggage too ÔÇö the hype of a big book deal and the frisson of a roman ├á┬áclef (her ing├®nue waits tables at a restaurant with the decor and location of DanlerÔÇÖs former employer, the Union Square Caf├®). But her novel is rarer than all that ÔÇö immaculately true to its time and place. Her food writing is lush and precise, her party scenes generous in substance(s) without McInerneyÔÇÖs glamorizing, and her confiding narrator, Tess, a raw, knowing, and crisp companion.

Secondhand Time: The Last of the Soviets, by Svetlana Alexievich, trans. Bela Shayevich (Random House, May 24)

In the Soviet era, when the Belarusian oral historian couldnÔÇÖt get published, erasure of the past was a state-sanctioned given. In the two decades after the collapse it was simply a dangerous habit ÔÇö one that paved the way for Putin. Alexievich, who won last yearÔÇÖs Nobel Prize in literature, roams that quasi-democratic interregnum in her fourth work of kaleidoscopic journalism. Some of her subjects are nostalgic, even for Stalin; others despair or rage at YeltsinÔÇÖs failed utopia; a select few even express hope. But all the voices are heard, for the first, and hopefully not the last, time.