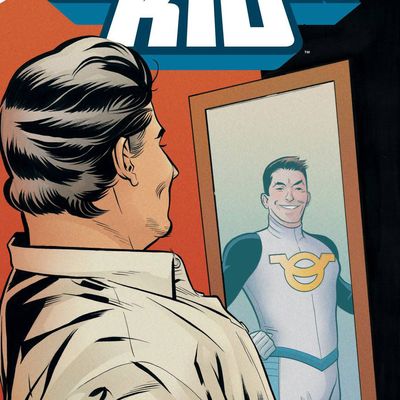

Superhero stories were first created for young people, and youth — or at least youthfulness — has been a dominant theme in the genre ever since. You rarely hear Spider-Man, Superman, or Wonder Woman complaining about arthritis or late Social Security checks. But what if a sprightly super-person had a middle-aged secret identity? That’s the pitch behind AfterShock Comics’ Captain Kid, an upcoming comics series written by industry veterans Mark Waid and Tom Peyer and penciled by Wilfredo Torres, which hits stands July 6.

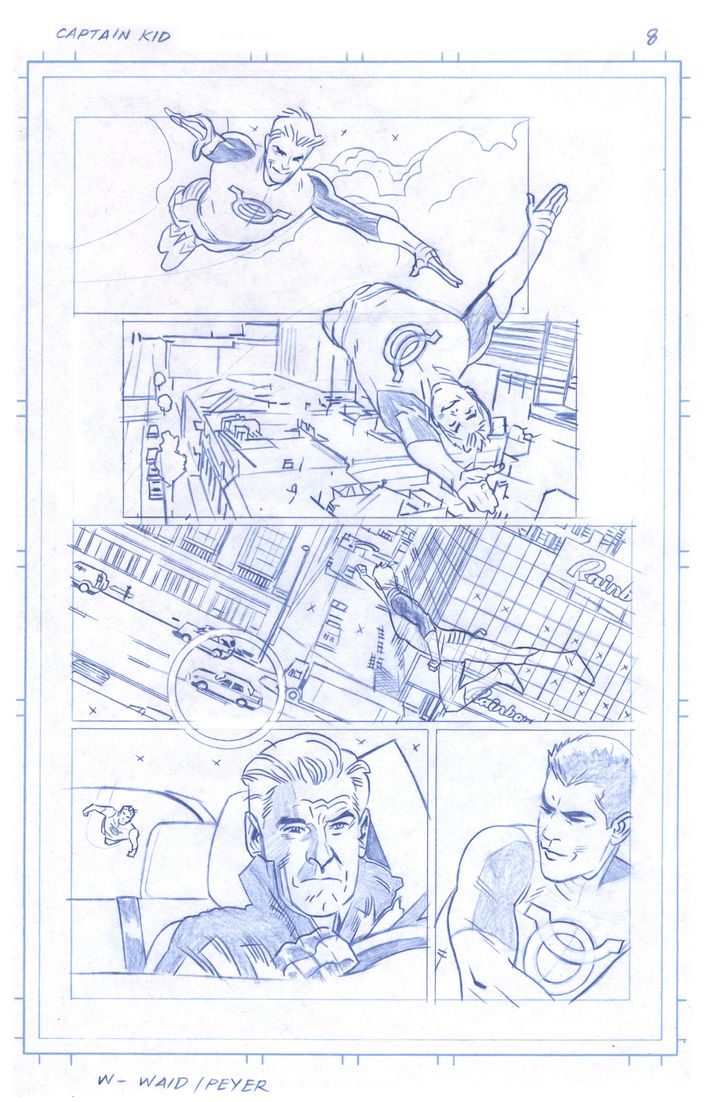

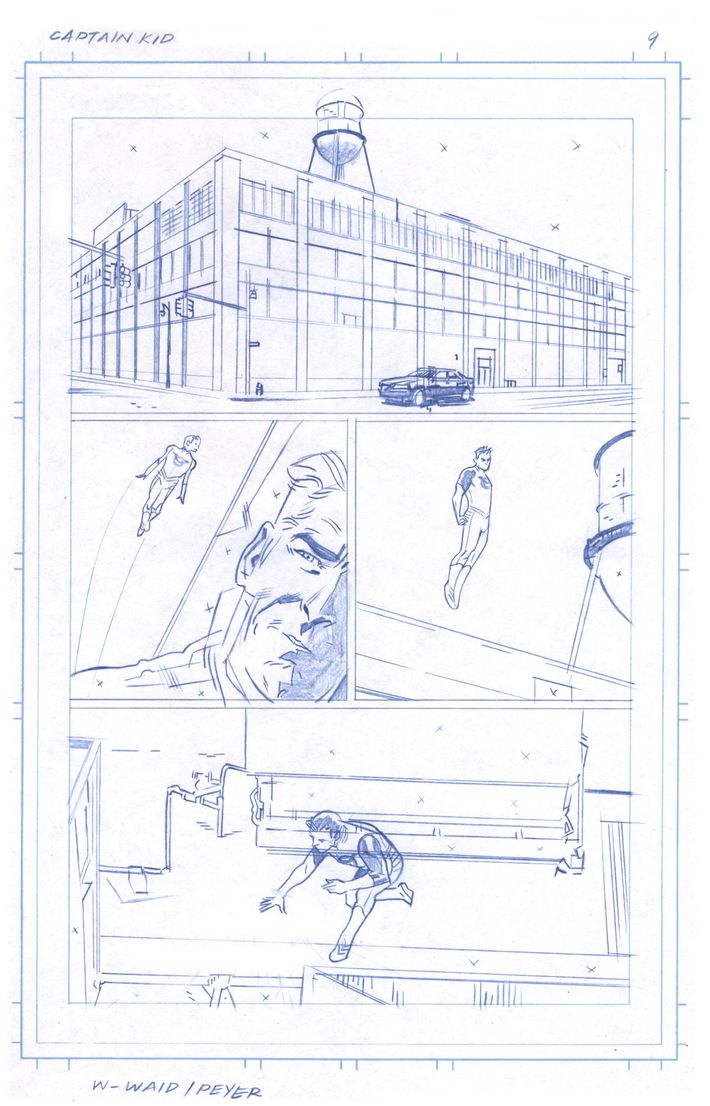

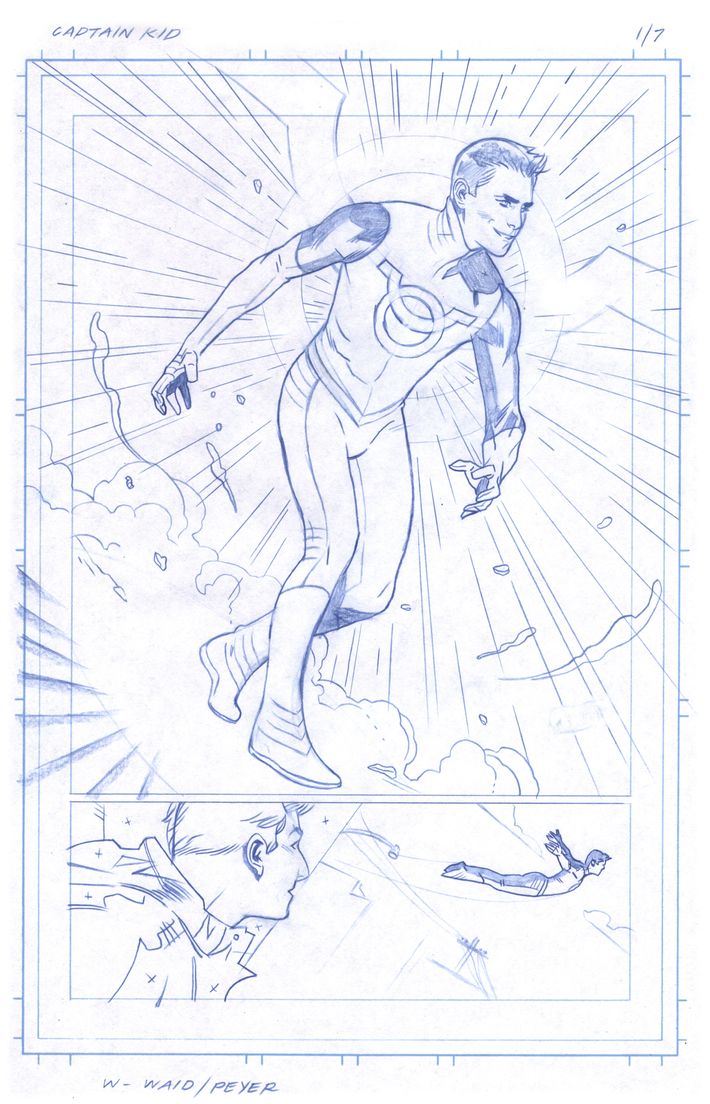

It follows 45-year-old Chris Vargas, who can transform himself into a 15-year-old superhero. The simple gimmick belies a deeper exploration of aging and what makes life worthwhile when you’re no longer a spring chicken. After all, if Chris can become a teen whenever he wants, why does he ever bother to change back? We caught up with Waid and Peyer to find out whether they would ever change back, as well as the challenges of coming up with new superhero stories after 75-plus years of the genre’s existence. Plus, there’s exclusive artwork from the first issue.

This project’s been brewing for a while. What were its origins?

Tom Peyer: It was an idea that crossed my mind a long time ago — as early as 2003. It was just sort of nutshell of an idea, and as I like to say: If I bring anything to comics it’s my own unique brand of inertia, so I really did nothing on this except talk to Waid about it every couple years. This year, he said, “Let’s do it. Let’s do it together,” and I thought: Great!

Mark Waid: I love this idea. I’ve loved this idea since the very first time he ever told me about it, because not only do I like the idea, but it was the name “Captain Kid” that I think was such a perfect fit for this thing. I’ve been pestering Tom for years to do something with it.

Peyer: I’m actually glad we waited till now, because it seems like it could be kind of an antidote to some of what’s going on in comics. We want Captain Kid to be an adult comic about wish fulfillment, and I don’t know if there are any others like that at the moment. Adult comics really seem to be about miserable people doing miserable things. Which is fine, and I’m all in favor of it, but not every time. There are a lot of shame-based comics that want to seem important, more important than they are. It translates into certain movies, too.

What do you mean by “shame-based”?

Peyer: “Shame-based” is: Well, the hero can’t have a brightly colored costume, and the hero can’t be basically good, because that’s baby stuff and I want my parents and my teacher and my boss to know that comics are for grown-ups who read about rape and murder.

Waid: Right, right.

Peyer: To me, the idea of making a Superman movie about how power corrupts is to me the most perverse thing I can imagine. So I hope this is a bit of an antidote to that. I don’t want all that other stuff to go away, I don’t hate it. But please, let’s have something else too.

Waid: And that’s not to say this is a comic that has no emotion or gravitas to it. It’s not “retro” by any stretch. You want there to be a voice to it and you want there to be some genuine human emotion in it; that’s how it connects. At the same time, it’s a superhero comic. Every time I see a superhero comic that’s cynical, that’s about how awful it is to be a superhero, it just sounds like, Oh no, my diamond shoes are too tight! You can fly! Shut up!

What’s your collaboration process?

Waid: We get on the phone, we try to one-up each other, we try to make each other laugh. The smartest thing I ever heard about storytelling was from an advertising guru named David Ogilvy. He said the best ideas start as jokes. That’s absolutely right. Because a joke immediately provokes a reaction — you either know whether you’ve got something provocative or not. And it’s loose. So a lot of what we talk about is just trying to make each other laugh, but also finding a truth in that moment, and finding drama in that moment, knowing that if Tom’s reacted to something I’ve said or vice versa, it means there’s something worth pursuing.

What parts of each of you are in Chris? What do you relate with him about?

Peyer: We made Chris an employee of an alternative weekly newspaper partly to show that, as his age advances, he’s becoming more and more obsolete. He’s the music editor of an alt weekly, which is a vanishing job and it used to be a badge of youth. It certainly isn’t that anymore.

Waid: It speaks to one of the friction points that keeps the collaboration strong. The tag line of the series is, “If you could change into a teenage superhero, would you ever change back?” Why would you ever change back? Tom and I have two completely different points of view on this. My attitude is, No! I would never change back. Not for one heartbeat. What are you, crazy? Tom has a much more nuanced, adult attitude about it.

Peyer: If Mark could become Captain Kid, I would never see or hear from him again. If I became Captain Kid, I would change back every once in a while to see my family, talk to my friends, do some of the things I’ve always been interested in doing. I would love to have a double life like that. Even if it meant that, when I change back to my real age, I would have a lot of aches and pains. I had slipped a disk in my back last month, which has really helped the story because I feel as decrepit as it’s possible to feel.

Why is that something that you would go back to? Why not just stay a teenager?

Waid: Yeah, Tom! Tell me!

Peyer: It’s not that I’d want to be a man of advanced years. It’s that I don’t want to cut everyone that I know out of my life. I would feel too guilty to show up to them and go, “Hey, look, I’m young again.” That might really color our relationship in a bad way. “Hey, I might be immortal! How are you feeling?”

Have you guys already gotten interest about adapting the comic for film or television? You hear about creators getting deals these days before the first issue of the comic comes out.

Peyer: Are you offering?

Waid: Nothing yet, but I get pinged a lot about stuff. I tend to be point guy on this. I’m easier to find on the web than Tom. I would be surprised if somebody wasn’t ringing the phone at some point sooner than later.

Peyer: They all read Vulture, don’t they?

We’re movie-industry kingmakers over here. You’ve both been in the comics business for a while now. What’s the biggest challenge the industry faces these days?

Waid: The signal-to-noise ratio is the biggest thing we have to overcome. The upside to digital, to having all of your comics available anywhere in the world, is spectacular. That’s what we’ve been wanting for 30 years, to be a mass medium again. But there’s so much out there, not just with comics but in terms of all your other entertainment choices. When we were kids you either read comics or you went outside and played stickball. The competition for eyeballs in the Wild West of the internet is an enormous challenge. It helps that the movies are out there, because they can draw focus to not only the superheroes but also the more mainstream non-superhero stuff in comics.

Peyer: I have to say: In my long, vast, context-filled life, I wouldn’t have expected to be talking about a comic book to New York Magazine or any brand associated with it. It’s really opened up. There’s a lot more competition, but there’s more ways to get your message out.

How does one find new things to say within the superhero genre now that it’s been around for 75-odd years?

Waid: Pay attention to the world. And I don’t mean just what’s happening, but what people feel. What’s going on on a gestalt level? What is the mood of the country? What is the mood of the world? Play off of that. That, to me, is the secret. Eventually, you’re gonna run out of names and you’re going to run out of superpowers. Eventually, you gotta start doubling up on things. That pool is only so deep. It’s about the way the writer is willing to give a character context in a way that has something to say about the world you live in today. That’s a really pretentious-sounding answer, but I genuinely believe it.

Peyer: You make me sick. But that’s true. Most of these characters in these movies have been around for 50 years, but that doesn’t mean all the great ideas were used up 50 years ago. It only means that they’re the most enduring brands. They’re pre-sold, so you can get people into the movies. It’s true on a comic rack too. It’s a lot harder to launch something than it is to do a nice Batman title or something. It has nothing to do with concept. It’s the brands.

Peyer: Which is why I’m going to have Captain Kid’s logo branded to my skin.