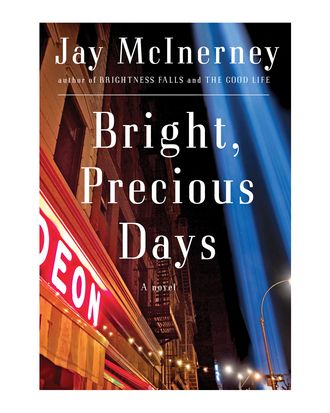

Jay McInerneyÔÇÖs new novel, Bright, Precious Days, is the third volume in his trilogy following the marriage of Russell and Corrine Calloway, two emblematic Ivy LeagueÔÇôeducated Manhattan yuppies from the class of 1980. Though formally unconnected to McInerneyÔÇÖs 1984 blockbuster, Bright Lights, Big City, the trilogy extends its themes of hedonism, aspiration, heartbreak, and tattered innocence beyond the callow boundaries of 20-somethingness and out into middle age. Bouts of adultery coordinated to recent historical events are the architecture of all three books. Brightness Falls (1992) saw the couple passing 30 en route to the market calamity of October 20, 1987; in The Good Life (2006), the September 11 attacks gave a jolt to their seemingly tranquil 40s; the new novel, set mostly between the 2006 midterm elections and autumn 2008ÔÇÖs cocktail of Obama hope and Lehman Brothers dread, sees them grasping one last time (perhaps) for pleasures beyond their marriage. Time passes, but the temptations of cocaine, blow jobs, and easy money remain, albeit in increasingly desperate and pathetic iterations.

On a broader scale, the trilogy dramatizes the struggles and entanglements between what Russell and Corrine think of as Team Art and Love and Team Power and Money. ItÔÇÖs a battle thatÔÇÖs impossible to escape in Manhattan, where in McInerneyÔÇÖs conception thereÔÇÖs always someone richer to sleep with or to provide an idealistic bohemian with leveraged-buyout financial support. McInerney recently told The Paris Review that he conceived of the books as an ongoing ÔÇ£counterlife,ÔÇØ in which he imagined the life of a man in an enduring marriage with a steady day job as a book editor, as opposed to his own life as a onetime literary wunderkind and persistent best seller now married to his fourth wife. A romantically minded child of the Midwest like FitzgeraldÔÇÖs similarly named Nick Carraway, Russell Calloway is one of those book editors who enter the profession despairing of their prospects as poets and of the unpredictable dislocations and likely obscurity in store for academics; he comes to Manhattan to reunite with his college sweetheart (he and Corrine met at a Brown frat party) while trying to become ÔÇ£to my era what Max Perkins was to his.ÔÇØ In Brightness Falls, heÔÇÖs made his name at a young age publishing a short-story collection by his best friend Jeff Pierce, a downtown libertine with an escalating drug habit. But Russell fears for his job security at Corbyn, Dern, a Norton-ish independent publisher. In cahoots with one of its founderÔÇÖs heirs, a pal of the recently deceased Andy Warhol, he launches a hostile takeover of the company.

The Good Life makes fewer gestures toward the comic, and the bookÔÇÖs center of gravity tilts away from Russell toward Corrine. Throughout the trilogy, she undergoes a perpetual career crisis: an assistant job at SothebyÔÇÖs, a stint as a stockbroker, a stab at screenwriting, etcetera. Now in her 40s, sheÔÇÖs given birth to twins, but with eggs provided by her flaky younger sister Hilary, and is professionally unmoored. The novel begins with a pair of September 10 set pieces, then hops to September 12, ÔÇ£Ash Wednesday.ÔÇØ The book is an uneasy mix of 9/11 elegy and Manhattan lifestyle novel, and the overflowing pop-culture references of Brightness (Russell just loves the Rolling Stones) yield to micro-details of food, wine, and fashion. McInerney spends a lot of pages painting Luke, a banker Corrine has an affair with, as an enlightened and disillusioned (yet also successful and rich) veteran of the private-equity trenches. The effort is strained. McInerney is at pains to show ground zero as a place where the cityÔÇÖs gritty working stiffs and its glamorous socialites achieved communion, sponsored in part by Ralph Lauren. No doubt thereÔÇÖs some truth to this schematic idea, but the novel only soars when these class dynamics fade out. In The Good LifeÔÇÖs one truly powerful passage, Luke describes to Corrine joining a line pulling bodies out of the wreckage and finding himself standing in a puddle of blood. The image has the effect of blotting out the novelÔÇÖs central adultery plot.

Bright, Precious Days recapitulates the strongest and weakest aspects of Brightness Falls and The Good Life. RussellÔÇÖs editorial activities are again a prompt for satire of familiar literary lore. A bright young blogger is after the original manuscript of Jeff PierceÔÇÖs Youth and Beauty, raising questions about RussellÔÇÖs interventions in a book based on his own marriage. Jack Carson, a young short-story writer from the hardscrabble, meth-infested woods of Tennessee, drops Russell as an editor for just that reason ÔÇö shades of Max Perkins and Thomas Wolfe as well as Raymond Carver and Gordon Lish. Now the head of another independent publisher, Russell bets the house on a memoir by a writer who was kidnapped by the Taliban and escaped ÔÇö a story soon exposed as a fraud. Corrine and Luke have meanwhile reunited after years of silence, though itÔÇÖs a little hard to tell why. Subplots about the infidelities and drug habits of those in the CallowaysÔÇÖ circle proliferate, and a couple of flashbacks to CorrineÔÇÖs tryst with Jeff Pierce in the ÔÇÖ80s inject a needed bit of youthful juice. A few losses are registered on the way to a happy ending. A brownstone is purchased, and the marriage endures.

What to make of this trilogy, which now totals 1,150 pages and could reasonably be called Tolstoyan, both in terms of its length and its committed consideration of the Calloways and their Manhattan? ÔÇ£You are not the kind of guy who would be at a place like this at this time of the morning,ÔÇØ goes the famous opening line of Bright Lights, Big City. That sort of question ÔÇö am I the kind of person who launches a hostile takeover, cheats on a spouse, still snorts coke? ÔÇö and its more generic corollary ÔÇö am I a clich├®? ÔÇö govern the entire Bright-Good-Precious trilogy. McInerney is of course aware of this, and his willingness to dive toward the clich├® as if it were GatsbyÔÇÖs green light is a strange form of daring. History sometimes favors the least common denominator, and in this respect it may be on his side.

*This article appears in the July 25, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.