“are you going to stick with coffee?” asks Amy Adams. “Will you be offended if I got myself something a little stronger?”

It’s late afternoon on a Friday in late July, and we’re in the glittery sepulchral swank of the Palm Court at London’s Langham Hotel. After a long day playing Lois Lane looking adoringly at Superman, maybe Adams needs a drink. She’s just come from a poster shoot for Justice League, which is, for reasons she says are unrelated to its plot, filming in this post-Brexit metropolis.

Then, suddenly remembering she has to work on Saturday, Adams, not really the screw-it type, backtracks, ordering a jasmine tea.

But the real reason she needed booze: “It makes my bones ache to talk about myself so much. It hurts!” Really, if given the choice, she’d much rather sing, and as the hotel bar’s piano man occasionally hits on something she finds irresistible, she’ll do just that. It’s unsurprising that she knows the words to “One,” the finale from A Chorus Line (“I could do the choreography for you, too”), but who remembers Dean Friedman’s 1978 hit “Lucky Stars”? “You can thank your lucky stars / We’re not as bad as we think we are,” she can’t help but sing.

“It’s just schmaltz. I love it.” Adams is almost suspiciously unnarcissistic for a Hollywood star, gracious, hardworking, and decent to the point of almost not being a “celebrity” in the contemporary sense of the multi-platform branded scandal entities we’ve learned to follow on Instagram (she’s not on social media). The former high-school gymnast, Gap greeter, and cartoon Disney princess who fell into a well and emerged, magical innocence intact, in jaded Manhattan with the ability to charm roaches into doing her housework — okay, that last bit was the character she played in 2007’s Enchanted — does not often give over to brooding or existential complaint. She is as present as any self-help book would prescribe (and she reads a lot of them). Joaquin Phoenix, with whom she worked on The Master and Her, nicknamed her Angry Adams, because she never is.

This fall, she has two films out, both of which could add to her current tally of five Academy Award nominations (or perhaps finally land her a win). First, on November 11, there’s the “these aliens have landed and are they friendly?” mind-bender Arrival, directed by Sicario’s Denis Villeneuve, in which she plays a linguist tasked with figuring out how to read or write spaceperson in a hurry. Her co-star is Jeremy Renner, who plays a physicist on the earthling welcoming committee. The film is notable in part for its Carl Sagan–ish tone of wonder, which is a nice contrast to the interstellar xenophobia and end-times paranoia of most extraterrestrial fare. But also for the way it grounds a sci-fi plot with the personal tragedy of Adams’s character and chews over various philosophical notions of choice and fate.

And then, not long after Arrival, comes Nocturnal Animals, based on Austin Wright’s 1993 novel Tony and Susan and directed and written by Tom Ford, in which she plays a well-off middle-aged woman who gets an unsettling manuscript in the mail written by her long-gone ex-husband. Jake Gyllenhaal is in that one, along with Isla Fisher, who the internet often says is Adams’s look-alike. (She plays a version of Adams’s character in the novel-within-a-novel the film is structured around.)

Adams is known for her big eyes — she even starred as artist Margaret Keane in Tim Burton’s Big Eyes — which are soulful and honest and vulnerable (and she does cry easily). To this day, she says, “I don’t think of myself as a celebrity. It’s not a part of my pursuit.” But then she adds, lest she offend: “Nothing against those who do.” She’s famous, of course — she has to explain to her daughter why, when they go out, people are sometimes filming them on their camera-phones. But “I am still really naïve,” she says. “I am continuously shocked.”

By what?

“The world! How people behave. Like, it would never occur to me to post a picture of myself in my underwear on Twitter. Maybe the 20-year-old me — I shudder to think of what I would have done in my moment of desperation and seeing what I might’ve chased.”

She is even more delicately beautiful in person than she often registers in films, whether it’s the heedlessly optimistic pregnant backwoods chatterbox in Junebug, the brutish Lady Macbeth of The Master, or the pouty Julie of Julie & Julia. If anything, she so inhabits her portrayals that it can be easy to forget they’re all her: The tentative nun in Doubt was the combatively vulnerable Southie gal Charlene in The Fighter. But, outside her turn as a con artist in American Hustle, she rarely is asked to play aggressively sexed-up. She was once accused by a writer in Esquire, who was apparently unable to discern what she actually looks like through the characters she plays so deftly, of being “perfectly plain.”

Which is, if you think of it the right way, a compliment of sorts.

Adams was born in 1974 in Italy, where her father was stationed in the Army, the fourth of seven kids, and grew up in the Denver exurb of Castle Rock. Her parents were Mormons, and they didn’t have much money. “I don’t imagine my parents read a lot of parenting books,” says Adams, who reads them all the time.

“I think my childhood experience started as one thing, a traditional place, and then ended in another,” she says. “It sort of morphed. My parents were good Mormons, and church was an important part of our social interactions.” But then her folks divorced when she was 12 and left the church and she lost that structure. She found a new one, first in dance, then in singing, and finally, when she was out of high school (she skipped college), in musical dinner theater.

She only moved to L.A. after getting a role in the 1999 beauty-pageant spoof Drop Dead Gorgeous, which happened to be filming in Minneapolis, where she was performing at the time. She’s credited the movie’s star, Kirstie Alley, with encouraging her, and she and one of her brothers drove west.

She quickly got work on various TV shows (a guest spot on Buffy the Vampire Slayer, then something called Dr. Vegas) but struggled to gain traction. In 2002, Steven Spielberg cast her as the candy striper who falls for Leonardo DiCaprio in Catch Me If You Can. But then, another slump. By 2004, she was turning 30 and considering the daunting prospect of finding something else to do with her life. Then a tiny indie film, Junebug, gave Adams her first Oscar nomination.

Here in London, Adams isn’t staying in the luxe Langham, which was opened in 1865 and claims to be the site where afternoon tea was invented. When she’s on a long shoot, she rents a house and her husband, Darren Le Gallo, a visual artist she met in an acting class in 2001, and their 6-year-old daughter, Aviana, come to stay. Adams pulls out her iPhone, and we scroll through some of Le Gallo’s surrealistic, somewhat anxious works. “I like this one,” she says of a painting, Hall of Photos. Then adds, deadpan, “It’s him with his head exploding.”

Arrival is based on “Story of Your Life,” by Ted Chiang. “It was a tough little short story to adapt,” admits Villeneuve. Even coming up with a title, he says, was “a long journey,” and they referred to the project by the acronym soyl for a long time since Chiang’s title “didn’t convey the idea of the movie,” sounding instead like a “romantic comedy or something.”

Which it isn’t, although Adams and Renner, whom she’s known since they did karaoke at Barney’s Beanery in L.A. 15 years or so ago, have good chemistry.

Given that the film riffs on how the aliens’ “simultaneous consciousness” allows them to “enact chronology,” and how Villeneuve and his stars swing between interspecies interactions (requiring big sets and CGI) and a quieter, personal story, it was, by all accounts, a difficult film to make narratively coherent.

“One of the big challenges was to link both of the extremities” — the epic and the intimate — “and keep tension alive,” says Villeneuve. In order to do that, “I needed an actress with a real wide range and a lot of intelligence to her eyes.”

Ford cast Adams for her eyes, too. “Since she’s mostly reading,” he says of Adams’s character, “we have to know what she is thinking and feeling through her face. Her eyes — there’s an instant connection when she looks at you. It’s like you’re looking inside her soul. It’s almost unsettling.”

But he didn’t just like her eyes. “I think American Hustle was the first time a lot of us realized how beautiful she was,” says Ford. “God, how beautiful her breasts are. It was a surprise. It was like, Wow.” He pauses, considering how that quote might read. “As a gay fashion designer and not a lecherous straight man, I can say that.”

That sort of response makes Adams laugh. “I got such great reactions to the way my character looked in American Hustle,” she says, shaking her head. “I thought, This girl is twisted. She lies to everybody and people love her. People had so many less questions about character development — playing someone who was living a lie within a lie — and so many more about my cleavage.” The character’s corruption bothered her so much Adams cut her hair short after the shoot to exorcise her.

She sips her tea. “I used to yell at my manager because I would get brought in to play the model version of me, and the model version of me would always get the part,” she says. “And my manager said to me, ‘You can either chase that or you can chase something else. What path you do want for yourself?’ And you realize that me going to an audition where I am standing next to Jaime Pressly in a bikini is not going to work. I had to realize pretty early on what I wasn’t. But I did chase that other thing.”

Adams has long been chasing the dream of making a movie based on the life of Janis Joplin. (She’d play Janis.) I ask why. “When people first brought the project to my attention, I said, ‘I can’t do this; people would judge me and tell me all the reasons that I am not like her.’ And then when I started reading about her, I realized that she was this beautiful human plagued by things which are so common. She had a need to find something.” She goes on: “People saw this huge personality, but there was this soulfulness and this screaming child inside of her.”

Adams has other alternate versions of herself she’d like to play, too, like “Aldonza in Man of La Mancha.” You know, the lusty wench who sings “Born on a dung heap to die on a dung heap / A strumpet men use and forget!”

But “that’s not going to happen anytime soon, since I’m not an old Spanish whore,” Adams says wryly. “You know, you come to an understanding of yourself.”

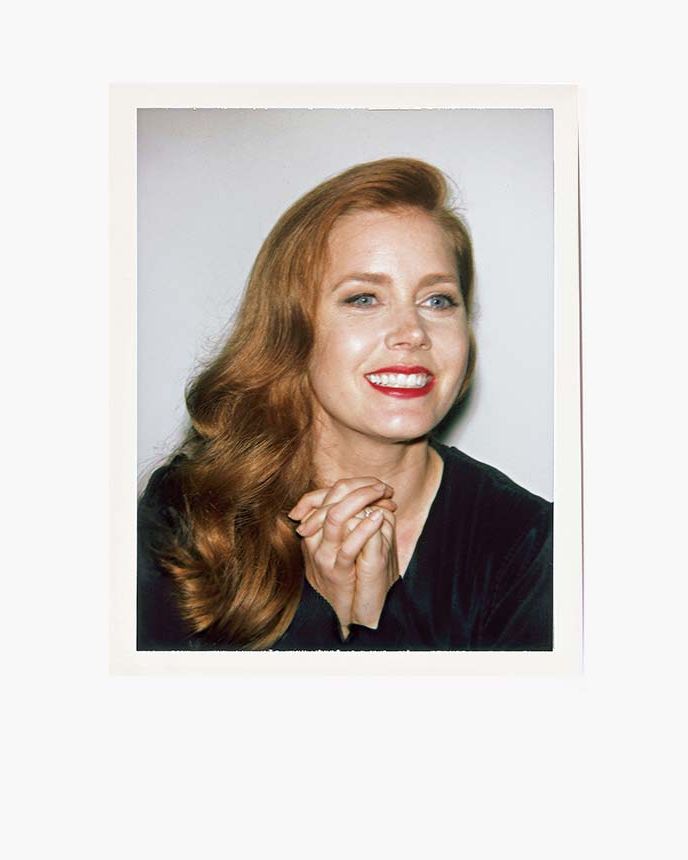

Opening Photo: Styling by Hew Hood; Hair by Ken O’Rourke; Makeup by Liz Pugh

*This article appears in the August 22, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.