How many plots are there in fiction? Millions, two, or 36, depending on whom you ask. ThereÔÇÖs William Wallace CookÔÇÖs chart-crazy Plotto, first published in 1928; thereÔÇÖs crisp guides like Christopher BookerÔÇÖs The Basic Seven Plots and Ronald B. TobiasÔÇÖs 20 Master Plots; thereÔÇÖs even a couple of computer programs ÔÇö many, over centuries, have tried to count the ways to tell a story. With a little help from those, here is a far-from-comprehensive encyclopedia of every archetypal plot we know.

A

Adultery

Anna Karenina, by Leo Tolstoy; The End of the Affair, by Graham Greene; Little Children, by Tom Perrotta.

A perennial plot device that has survived the weakening of social taboos. What once caused shame and suicide now often ends in reconciliation. (see also: Forbidden Love.)

Adventure, Allegorical

The Chronicles of Narnia, by C.ÔÇàS. Lewis; The Master and Margarita, by Mikhail Bulgakov.

The current is closer to the surface in stories rife with symbolism, though in modern times it tends to be less on the nose.

Adventure, Natural

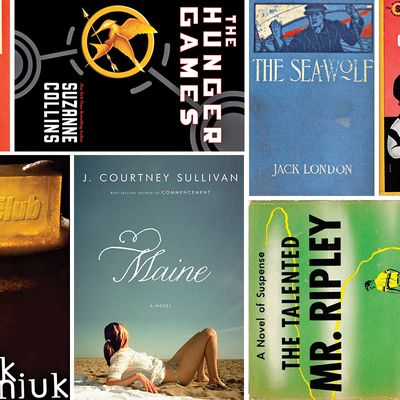

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, by Jules Verne; The Sea-Wolf, by Jack London.

A usually itinerant story in which action is the prime directive, even if deeper currents run below. (see also: Quest.)

C

Coming of Age

Great Expectations, by Charles Dickens; Huckleberry Finn, by Mark Twain.

The bildungsroman, as the Germans call it.

Coming of Age, Artistic

A Portrait of the Artist As a Young Man, by James Joyce; The Fortress of Solitude, by Jonathan Lethem.

This subtype has its own German term, too: K├╝nstlerroman.

Coming of Age, Group

The Group, by Mary McCarthy; The Interestings, by Meg Wolitzer; Private Citizens, by Tony Tulathimutte.

Characters converge ÔÇö usually in high school or college ÔÇö and then diverge. But changed!

The Con

Dead Souls, by Nikolai Gogol; If Tomorrow Comes, by Sidney Sheldon.

Who doesnÔÇÖt want to root for a seasoned liar and criminal?

The Con Artist Gets Conned

The Grifters, by Jim Thompson; The Mark Inside, by Amy Reading.

A swindler is double-crossed, either out of vengeance or greed. (see also: the Impostor; Spy-Versus-Spy Story.)

D

Death Plot

The Death of Ivan Ilyich, by Leo Tolstoy.

Facing a slow demise or a pending execution, the condemned seeks absolution or a reckoning with the universe.

Death As MacGuffin

My SisterÔÇÖs Keeper, by Jodi Picoult; The Fault in Our Stars, by John Green.

The ÔÇ£wrongÔÇØ person dies.

Descent Into Madness

Tender Is the Night, by F. Scott Fitzgerald; Mrs. Dalloway, by Virginia Woolf.

A characterÔÇÖs fall is described, sometimes luridly but often sympathetically.

Descent Into Addiction

The Lost Weekend, by Charles Jackson; Trainspotting, by Irvine Welsh.

Same trajectory as madness, just add problematic glamour.

Discovery of Hidden Parentage

Great Expectations.

One of the most reliable plot twists, this one often changes the characterÔÇÖs self-identity, for better or worse.

Discovery of Incest

Dolores Claiborne, by Stephen King; A Song of Ice and Fire, by George R.R. Martin

This tends to have grave plot consequences, like murder and succession crises.

Discovery of a Lie

The Portrait of a Lady, by Henry James.

The protagonist is deceived through much of the story until the scales fall from her eyes. Like coming-of-age stories, it pivots on a revelation, but here the knowledge was purposely hidden from the protagonist ÔÇö or in some cases, as in Gone Girl, by the protagonist.

Discovery of the Secretly Alive

Romeo and Juliet, by William Shakespeare; Our Mutual Friend, by Charles Dickens.

It sounds like a happy surprise, but this late twist doesnÔÇÖt always turn out to be a good thing.

Discovery of the Secretly Nonexistent

Fight Club, by Chuck Palahniuk; Odd Thomas, by Dean Koontz.

Wherein people turn out to see dead people ÔÇö or imaginary ones.

Domesticity Meltdown

A DollÔÇÖs House, by Henrik Ibsen; Revolutionary Road, by Richard Yates.

Someone, usually a woman, finds her home life unbearable and takes or contemplates extreme measures. (see also: Wife As Phoenix.)

E

Estate Division

A Perfectly Good Family, by Lionel Shriver.

A family gathers in the wake of the death of parents to figure out what to do with their effects; old conflicts resurface. (see also: Family Reunion.)

F

Family Reunion

This Is Where I Leave You, by Jonathan Tropper; Maine, by J. Courtney Sullivan.

A vacation or a death brings a far-flung family together; old conflicts resurface.

Family Saga

Buddenbrooks, by Thomas Mann; Homegoing, by Yaa Gyasi.

Where many ambitious novels bring contemporaneous stories together, this megaplot tracks a single clan across a broad sweep of time. (see also: Rise and Fall.)

Forbidden Love, Tragic

Romeo and Juliet; Anna Karenina.

A deep infatuation whose obstacle is a feud or social taboo that ends very badly. (see also: Love Thwarted and Mourned.)

Forbidden Love, Triumphant

Water for Elephants, by Sara Gruen; Fifty Shades Freed, by E.ÔÇàL. James.

Love conquers all ÔÇö abusive husbands and sad billionaires alike.

G

Good-Guy-Bad-Guy Alliance

To Catch a Thief, by David Dodge; The Silence of the Lambs, by Thomas Harris.

A cop or other white-hat teams up with a criminal to fight an even greater evil, forming an unstable and unpredictable team.

I

The Impostor

The Talented Mr. Ripley, by Patricia Highsmith; Six Degrees of Separation, by John Guare.

An anti-hero assumes a false identity and succeeds ÔÇö to a point. Sometimes the question of whether heÔÇÖll evade detection is left unresolved (or deferred to sequels and/or film adaptations).

InnocentÔÇÖs Tale

Room, by Emma Donoghue; The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, by Mark Haddon.

A child (or childlike) narrator can only tell a part of the story, leaving the reader to figure out the rest. (see also: Coming of Age.)

Insane Narrator

Fight Club; Life of Pi, by Yann Martel.

The unveiling of deception or hallucination by a seemingly trustworthy narrator becomes a perspective-shifting plot twist. ThereÔÇÖs an open-ended version: Is she crazy? Was it a dream?

K

The Knausgaard

My Struggle, by Karl Ove Knausgaard; The Waves, by Virginia Woolf.

Here named for KnausgaardÔÇÖs six-volume epic of seemingly unedited episodes from his life, this category of anti-narrative isnÔÇÖt quite plotless. For Woolf, it meant following consciousness where it goes, tracking the way the mind jumbles and reorders time. For Knausgaard, it meant repeatedly making tea.

L

Love Story: The Hate Plot

The Dance of Death, by August Strindberg; WhoÔÇÖs Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, by Edward Albee

A curdled kind of love creates tension, ambiguity, and great zingers. ItÔÇÖs the kind of tragedy you hate to love.

Love Story: The Marriage Plot

Pride and Prejudice, by Jane Austen; Jane Eyre, by Charlotte Brontë.

Traditionally, a woman turns down proposals of convenience and settles on an unexpected Mr. Right. While AustenÔÇÖs ÔÇ£truth universally acknowledgedÔÇØ ÔÇö that marriage is the end-all and be-all ÔÇö is on its way out, the plot seems to endure, albeit with an ironic gloss. Helen FieldingÔÇÖs Bridget JonesÔÇÖs Diary was only one of a slew of homages to the love plot,

updated for a more confusing and equitable era ÔÇö including Jeffrey EugenidesÔÇÖs The Marriage Plot. (see also: Forbidden Love.)

Love Story: Obsession

Othello, by William Shakespeare; Lolita, by Vladimir Nabokov.

An excess of love, sometimes less than mutual, drives the lover to violence or corruption, damaging the lover and/or the beloved.

Love Thwarted and Mourned

Love in the Time of Cholera, by Gabriel García Márquez; The Age of Innocence, by Edith Wharton.

A doomed or stillborn affair ends not in tragedy but in compromise, regret, and many wistful looks. (see also:

Forbidden Love.)

M

Me Against the Apocalypse

The Stand, by Stephen King; The Road, by Cormac McCarthy.

The universe being opposed is in rapid decline, and the struggle isnÔÇÖt against order but disorder (whether in the form of environmental collapse, nuclear winter, plague, or some other global comeuppance).

Me Against Machine

I, Robot, by Isaac Asimov; Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, by Philip K. Dick.

The technology we invented has broken loose and the resulting sci-fi adventure story usually doubles as a techno-skeptical dystopia.

Me Against the World

The Hunger Games, by Suzanne Collins; Nineteen Eighty-Four, by George Orwell; The Stranger, by Albert Camus.

One person resists an immovable power and either triumphs or submits. In dystopian fiction, that power tends to be an authoritarian government. The existentialists raised the stakes by pitting an individual against an unfeeling universe.

Metamorphosis, Internal

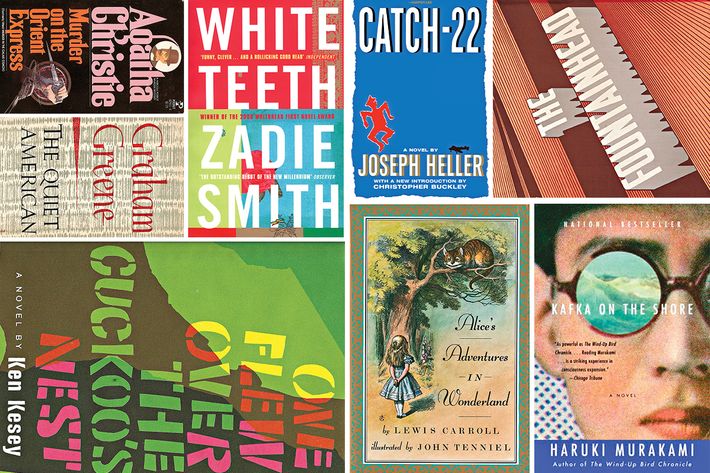

Pygmalion, by George Bernard Shaw; Catch-22, by Joseph Heller.

Someone is put through a trial by transformation ÔÇö which can yield unexpected results (Eliza DoolittleÔÇÖs independent streak).

Metamorphosis, Magical

Dracula, by Bram Stoker; The Metamorphosis, by Franz Kafka.

The (anti-)hero suffers from a transformative curse ÔÇö a spell that can only be broken by love or death.

Missing Person

WhereÔÇÖd You Go, Bernadette, by Maria Semple.

Lots of things can happen to people who disappear, which is also what you want from a plot.

Mistaken Identity

Our Mutual Friend; Scoop, by Evelyn Waugh.

An essential misunderstanding or deliberate deception drives the story in surprising directions. (see also: Discovery of the Secretly Alive.)

Mystery: Locked Room

Murder on the Orient Express, by Agatha Christie.

Whodunits were often classified as ÔÇ£riddle plotsÔÇØ by early plot anatomists, and the Platonic exemplar of the riddle is the ÔÇ£locked roomÔÇØ variety: Owing to circumstances laid out by the author, there are a finite number of suspects to a crime, and the readerÔÇÖs job is the same as the detectiveÔÇÖs: Figure it out from the available clues.

Mystery: Existential

The Trial, by Franz Kafka.

The puzzle is unsolvable, because the riddle is our unknowable and often hostile universe. (see also: Me Against the World.)

Mystery: Mirror Version

The Whites, by Richard Price.

The criminalÔÇÖs identity is revealed early on, so the reader knows more than the detective (but not enough to know what happens next).

Mystery: Open-Ended

The Big Sleep, by Raymond Chandler.

Chandler once wrote that half of all mystery books break the rule that all the tools for solving a murder should be clearly laid out. Enter the MacGuffin and other red herrings, complicated heroes who lie or mess up or just drink a lot. (see also: Quest, MacGuffin Variation; Pursuit, Conflicted.)

Mystery: Ticking Clock

The Silence of the Lambs.

The riddle must be solved in time to prevent the next heist, murder, or terrorist attack.

P

PandoraÔÇÖs Box

Frankenstein, by Mary Shelley; Jurassic Park, by Michael Crichton.

Scientists aim to advance technology in some way, and of course it backfires, because nature canÔÇÖt be tamed. (see also: Me Against the Apocalypse.)

Parallel Stories

The comedies of Shakespeare; Kafka on the Shore, by Haruki Murakami.

The plot is broken up among several sets of characters, whose conflicts are related but independent.

Picaresque

Don Quixote, by Miguel de Cervantes; On the Road, by Jack Kerouac.

Our (often roguish and working-class) hero moves from adventure to adventure or quest to quest, usually without maturing too much. Its modern American version favors the road trip. (see also: Tall Tales.)

Pursuit

Jaws, by Peter Benchley; The Hunt for Red October, by Tom Clancy.

Usually both a riddle and a chase, this action-heavy plot proceeds with a logical structure and noble, objective hero.

Pursuit, Moral-Ambiguity Variation

Les Mis├®rables, by Victor Hugo; The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, by Stieg Larsson.

A procedural or law-and-order drama is heightened when the righteous pursuer blurs ethical lines. (see also: Mystery: Open-Ended.)

Q

Quest, Classic

Don Quixote; The Grapes of Wrath, by John Steinbeck.

Both a pursuit and an adventure, but always with a tangible, redemptive goal.

Quest, MacGuffin Variation

The Maltese Falcon, by Dashiell Hammett; The Goldfinch, by Donna Tartt.

The object of the quest turns out to be a distraction, initiating the plot before giving way to the real drama. A MacGuffin can be any plot device that is superseded by a more important pursuit. (see also: Mystery: Open-ended.)

R

Rags to Riches

Oliver Twist, by Charles Dickens; The Fountainhead, by Ayn Rand; What Makes Sammy Run?, by Budd Schulberg.

Older examples might have involved sheer luck, but in more modern stories, the driver of mobility is ambition, whether celebrated or satirized.

Rashomon

The Sound and the Fury, by William Faulkner; Imagine Me Gone, by Adam Haslett.

Named for the Kurosawa movie, in which four witnesses offer conflicting versions of a murder, itÔÇÖs the same narrative retold from different perspectives. (see also: Symphony Story.)

Rescue

The Princess Bride, by William Goldman; The Hard Way, by Lee Child.

Essentially a quest with a person at the end of it ÔÇö a prisoner who has little agency in the story. (see also: Pursuit; Quest.)

Revenge

Hamlet, by William Shakespeare; The Count of Monte Cristo, by Alexandre Dumas.

The wronged protagonist finds his way to avenging injustice, usually by extralegal means.

Revenge, Excessive

The Cask of Amontillado, by Edgar Allan Poe; Medea, by Euripides.

The revenge plot with a heavy dose of crazy. Either the original slight is invented or magnified, or the vengeance is so out of whack (MedeaÔÇÖs murder of her own children) that all reason is left behind.

Rise and Fall

The Godfather, by Mario Puzo; One Hundred Years of Solitude, by Gabriel García Márquez.

A long story arc follows a person or a family to great heights and depths, often as the result of morally questionable choices along the way. (See also: Tragedy; Family Saga.)

The Rise of One, the Fall of Another

Sister Carrie, by Theodore Dreiser; The Prince and the Pauper, by Mark Twain.

The wheel of fortune turns, and one hero is brought low, the other high. If the one raised up is good, the moral is bright; if vice versa, we end up in a dark place.

Rivalry of Equals

Paradise Lost, by John Milton; Moby-Dick, by Herman Melville.

The fighters in the story need not be physically evenly matched; in fact, they work best when strengths are complementary (brains versus brawn, darkness versus light).

Rivalry of Unequals

ÔÇ£CinderellaÔÇØ; One Flew Over the CuckooÔÇÖs Nest, by Ken Kesey.

Underdog plots go back at least to the Bible. TheyÔÇÖre rivalry stories in which one (usually more righteous) party is weaker in almost all respects.

Rivalry of Unequals, Jealousy Variation

The Information, by Martin Amis; Amadeus, by Peter Shaffer.

Envy is at the root of such rivalries, and the underdog isnÔÇÖt the noble hero but the embittered loser.

Romantic Comedy

ShakespeareÔÇÖs comedies; Can You Keep a Secret?, by Sophie Kinsella.

Overcoming obstacles, the right people find each other and the mismatched are realigned. (see also: The Marriage Plot.)

S

Spy Story

The Quiet American, by Graham Greene; Martin Cruz SmithÔÇÖs novels.

Espionage thrillers contain plenty of riddles and ticking clocks, but they also encompass other story elements: globe-trotting pursuit, geopolitical intrigue, and layers of social history.

Spy-Versus-Spy Story

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, by John le Carr├®.

Spies often fight to outsmart and set traps for each other, and here the rivalry might even supersede the greater goal of intelligence gathering.

Symphony Story

White Teeth, by Zadie Smith; Underworld, by Don DeLillo; Ragtime, by E.ÔÇàL. Doctorow.

Several narratives intersect, collide, and sometimes culminate in a grand resolution meant to capture a larger societal moment. James Wood derided some of it as ÔÇ£hysterical realism.ÔÇØ

Stalker

Into the Darkest Corner, by Elizabeth Haynes; Sweet Lamb of Heaven, by Lydia Millet.

The Lifetime staple of story lines is diabolically simple: A man wont stop tormenting a woman until one of them dies. But there are variations 

Stalker, Caretaker Variation

Misery, by Stephen King; Notes on a Scandal, by Zoë Heller.

Often the predator is a single woman who becomes enmeshed with a man or family in a caretaking situation, then begins entertaining fantasies of making things permanent ÔÇö sometimes by lethal force. (see also: Love Story: Obsession.)

T

Tall Tales

The Decameron, by Giovanni Boccaccio; One Thousand and One Nights; The Canterbury Tales, by Geoffrey Chaucer.

Many ÔÇ£nested storiesÔÇØ are told or written by characters within the larger narrative, often becoming more important than the loose plot that frames them.

Tragedy

Hamlet; Oedipus Rex, by Sophocles.

Tragedies in the Aristotelian sense involve the downfall of a hero whose greatest weakness (which also may be a strength) makes defeat and disaster inevitable.

Trial

To Kill a Mockingbird, by Harper Lee; A Time to Kill, by John Grisham.

Somewhere between a genre and a plot device, the court case can be the central story or an event that clarifies social issues surrounding the alleged crime.

Trial by Suffering

The Book of Job; A Little Life, by Hanya Yanagihara.

Troubles are heaped upon our protagonist until he is left irreparably disillusioned or dead ÔÇö perhaps with just a hint of redemption at the end. (see also: Rise and Fall.)

Trial, Show

The Crucible, by Arthur Miller; Darkness at Noon, by Arthur Koestler.

Stories of witch hunts, literal and otherwise, might revolve around a courtroom trial or may more broadly feature mob justice, like Shirley JacksonÔÇÖs The Lottery.

V

Voyage and Return

Typee, by Herman Melville; AliceÔÇÖs Adventures in Wonderland, by Lewis Carroll; The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, by L. Frank Baum.

A kind of accidental quest: The goal is return, but the pleasure is in exploring a strange new world. (see also: Adventure.)

Voyage, Return As MacGuffin

Robinson Crusoe, by Daniel Defoe; The Martian, by Andy Weir; Lord of the Flies, by William Golding.

The stranded adventurerÔÇÖs escape is deferred and the plot stalls into a sort of social locked-room mystery. Will the hero survive? Can he remake society? (see also: Quest, MacGuffin Variation.)

W

War at the Front

Catch-22; For Whom the Bell Tolls, by Ernest Hemingway; War and Peace, by Leo Tolstoy.

Bloody conflict gives the story its structure, whether the attitude toward it is heroic, comic, or deeply critical (or all three!).

War on the Home Front

Cold Mountain, by Charles Frazier; War and Peace.

The effects of war and revolution are felt by those left behind; families are torn asunder and/or reunited.

Wife As Phoenix

Gone Girl, by Gillian Flynn; Fates and Furies, by Lauren Groff.

The story might begin with the wife mute or absent, or in any event cast in the role of long-suffering innocent. Then the narrative pivots, and as she tells her story, someone stronger and more calculating emerges.

*A version of this article appears in the August 8, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.