The American Western seems to be perpetually stuck on life support, clinging to a faint heartbeat of relevance. For every recent critical success (3:10 to Yuma, True Grit) thereÔÇÖs been a high-profile stumble (Cowboys & Aliens, The Lone Ranger) that inevitably leads to obituaries for the genre,┬áwith headlines like ÔÇ£How the Western Was Lost (And Why It Matters).ÔÇØ There is no end to possible variations on the Western, of course: WeÔÇÖve lately seen noir Westerns (No Country for Old Men), space Westerns (Serenity), and Tarantino-fied Westerns (Django Unchained, Hateful Eight). But these are typically artful repurposings of the same basic tropes that have animated the genre since the novel The Virginian popularized the ÔÇ£Wild West,ÔÇØ way back in 1902. On the horizon, we have Antoine FuquaÔÇÖs forthcoming The Magnificent Seven remake, looking to infuse the dusty genre with hip-hop swagger and scoring its cowpoke trailer to a bouncy remix of a track by Royal Deluxe. Yet even as Denzel WashingtonÔÇÖs team of vigilante horsemen gallops loudly toward theaters, a quieter movie slipped onto screens this month, suggesting an entirely different kind of Western reinvention ÔÇö┬áand relevance.

Though the traditional idea of the Western has birthed any number of subgenres ÔÇö┬áthe ÔÇ£WesternÔÇØ Wikipedia page lists 21 examples, from ÔÇ£spaghetti WesternÔÇØ to ÔÇ£curry WesternÔÇØ to ÔÇ£weird WesternÔÇØ ÔÇö┬áas a whole, the American Western can be roughly divided into two categories: the classic Western and the revisionist Western. The classic Western ruled in the 1930s, ÔÇÿ40s, and into the ÔÇÿ50s, and is the kind of portrayal that most readily comes to mind when you think of a ÔÇ£Western.ÔÇØ ItÔÇÖs Stagecoach, High Noon, or Shane; itÔÇÖs early John Wayne; itÔÇÖs Red River Valley. On TV, itÔÇÖs Bonanza, Maverick, and Gunsmoke. (ItÔÇÖs also Star Trek.) These are upright tales of the frontier as the last refuge of liberty and personal reinvention ÔÇö where lone men of virtue stand tall, as civilizing forces against lawlessness and (in various problematic depictions) savagery.

The revisionist Western came to the fore in the 1950s and ÔÇÿ60s, with films like The Searchers and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, which questioned, upended, or rebuked the established mythology. In these films ÔÇö and the capstone of the genre, which came in 1992, Clint EastwoodÔÇÖs Oscar-winning Unforgiven ÔÇö┬áthe frontier is no longer the vanguard of advancing civilization, but rather an anarchic realm ruled by cruelty and chaos, where men and women are loosed to act on their basest instincts. In literature, this is Cormac McCarthyÔÇÖs Blood Meridian; on TV, itÔÇÖs David MilchÔÇÖs Deadwood, which brilliantly forced the classic and revisionist approaches into a kind of narrative shotgun marriage ÔÇö as personified by the uneasy alliance between stalwart Sheriff Seth Bullock and the outlaw Al Swearengen.

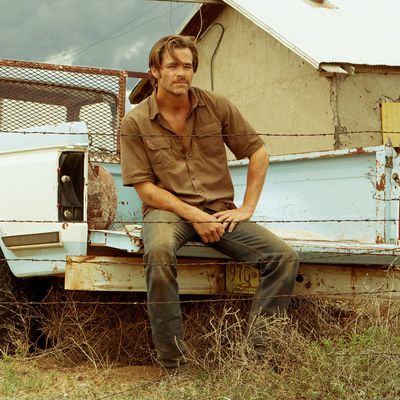

Then we have a movie like Hell or High Water, which opened in New York last week. Currently rated 98 percent fresh on Rotten Tomatoes, the film arrives as one of those classic bits of late-summer counterprogramming: a tight, taut caper film thatÔÇÖs the perfect antidote to blockbuster fatigue. (New YorkÔÇÖs┬ácritic David Edelstein praised it as ÔÇ£an amazing film ÔǪ a work of broad scale and deep feeling, a film to make you excited about the potential for finding new stories in old places.ÔÇØ) The film, directed by David McKenzie and written by Taylor Sheridan (Sicario), is a high-concept, contemporary tale of two brothers, Toby and Tanner (Chris Pine and Ben Foster), whoÔÇÖve taken to robbing a chain of banks that hold the mortgage on their soon-to-be-repossessed ranch. Jeff Bridges plays teetering-on-retirement Texas Ranger Marcus Hamilton, who follows the brothers in lukewarm pursuit. His character is so laconic that he seems like a meta-commentary on the trope of the laconic Texas lawman ÔÇö or, at least, a movie-length game of one-upmanship to Tommy Lee Jones as Ed Tom Bell in No Country for Old Men.

WhatÔÇÖs striking about the film, besides its taut pacing, smart script, and fine performances, is how it reimagines the Western in a strikingly relevant way. You can start with the familiar landscape: Yes, this is Texas, specifically West Texas, with its dusty plains and endless vistas. But the Texas in this film is a bleak, modern-day version of the classic frontier: bleached-out, wrung dry, economically withered, and largely abandoned. This movie presents the ÔÇ£WestÔÇØ as neither a land of eternal possibility nor a stage for moral anarchy, but rather as a broken promise ÔÇö a place barely populated by dispirited people with nowhere left to turn. This is the frontier in foreclosure.

That portrayal might sound familiar, since it echoes another recent unlikely reinvention of the Western: Breaking Bad. That show similarly shared little in common, at least superficially, with the Western genre (thereÔÇÖs nary a Stetson or swinging saloon door in sight), yet it too reimagined frontier mythology. The showÔÇÖs isolated meth labs and bungalow cul-de-sacs ÔÇö tiny repositories of economic despair ÔÇö are consistently set in sharp relief to the vast expanse of New Mexico. (Has there ever been a Western ÔÇö hell, a TV show of any stripe ÔÇö that consistently showed us more sky?) Here again is the ÔÇ£WestÔÇØ as an economically bereft region, where the frontier spirit is characterized by the ubiquity of going-out-of-business signs. The showÔÇÖs hero, Walter White, has more in common with Toby and Tanner of Hell and High Water than with Sheriff Will Kane of High Noon, or even with Clint EastwoodÔÇÖs William Munny in Unforgiven. White is also a man hobbled by despair, broken by circumstance, and slowly seduced by the allure of an outlaw alternative, which seems the only path left to him.

Another interesting potential ÔÇ£frontier-in-foreclosureÔÇØ specimen is HBOÔÇÖs Westworld, premiering in October. It takes inspiration from Michael CrichtonÔÇÖs pulpy sci-fi classic of the same name, and imagines a futuristic, Western-themed dreamworld in which every human fantasy is entertained. On the surface, the slick virtual promises of Westworld share little in common with the bleak landscapes of Hell or High Water and Breaking Bad, yet the show speaks to a similar desperation-driven hunger for reinvention by any means necessary. ItÔÇÖs too early to know exactly what sort of desperados will seek escape in WestworldÔÇÖs alternate realm, but itÔÇÖs not hard to anticipate another ongoing exploration of the friction between spent reality (economic collapse, the death of personal possibility) and bought-and-sold fantasies (you too can be an outlaw! Stick it to the people who done stuck it to you!).

In Hell or High Water and Breaking Bad, broken men look to reinvent themselves as figures of consequence. In Westworld, people are invited to reimagine themselves in any way they see fit. In all of these depictions, thereÔÇÖs an overriding sense of asphyxiating hopelessness that spurs these characters to shrug off societyÔÇÖs strictures. Westerns have always been, at their heart, about reinvention ÔÇö whether as a lone figure of valor on the far edge of civilization, or as a person unhindered by societyÔÇÖs moral conventions. In these new Westerns, the frontier is neither boundless, nor lawless ÔÇö itÔÇÖs bankrupt. And the only reinvention possible takes the form of an ill-fated struggle to take back some small measure of control over your fate.