This week, Vulture is taking a look at great unproduced, unreleased, or unheralded entertainment.

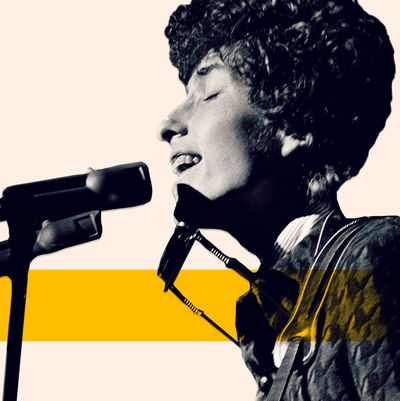

On May 17, 1966, at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester, England, Bob Dylan performed one of the most famous — and infamous — concerts in rock history. The show was the 11th of Dylan and his backing band the Hawks’ European tour, a series of gigs that on a nightly basis descended into battles. (Battles that, truth be told, have probably been overstated over the years.) A year prior, Dylan had “gone electric,” moving away from his acoustic protest-singer phase into rock music. Po-faced American fans had already fought their own struggles with Bob over this perceived selling-out, asserting that folk was musically pure and politically important, while rock was a fad, garish and shallow. In the spring of 1966, old-world listeners finally had a chance to jeer in person themselves.

The discontent came to a head on May 17 in Manchester when, after Dylan and his band had performed the taunting “Ballad of a Thin Man,” an audience member yelled “Judas!” Dylan hissed back, “I don’t believe you! You’re a liar!” Then he and the Hawks, who would later become the Band, exploded into “Like a Rolling Stone.”

The moment quickly became iconic, and it’s easy to understand why. The “Judas” show is the Ur-example of Dylan as an agent of artistic freedom. He was going to do what he wanted, no matter how angry it made people, and he was going to do it loudly. The moment stayed with Dylan, too. “Judas, the most hated name in human history!” he said in 2012. “Yeah, and for what? For playing an electric guitar? As if that is in some way equitable to betraying our Lord and delivering him up to be crucified. All those evil motherfuckers can rot in hell.”

It was hard to imagine the drama of that night — and for 32 years, it was even harder to hear it. The performance circulated as a bootleg, erroneously called the “Royal Albert Hall” concert, before it was officially released, in 1998, as the fourth volume of Dylan’s Bootleg Series of archival material. Non-obsessives could now hear what only dedicated Dylanologists had previously been privy to: the “Judas” concert consisted of thrilling electric rock and roll — boy, did history ever prove those blinkered folk fans wrong — and one of those rare instances where the legendary lost classic lived up to itself.

Yet as we now know, thanks to the fascinating, newly released box set The Live 1966 Recordings, which contains audio from every show on Dylan’s European swing, the Judas show wasn’t even the best concert of the tour. Ten days after performing in Manchester, Dylan was in London to close out the run of dates with two evenings at the actual Royal Albert Hall — and on the second night, May 27, 1966, the final show of the tour, Dylan played a gig that exceeds even the “Judas” concert for sheer intensity and resonance.

To get something out of the way: Each concert of the 1966 European tour was divided in two. The first half of every performance featured Dylan alone on acoustic guitar and harmonica, mostly sticking to a repertoire of hallucinatory, then-new songs like “Desolation Row,” “Visions of Johanna,” and “Mr. Tambourine Man” — songs that you’d have to be high to think were songs of explicit social protest. You might also need to a little psycho-spiritual enhancement, 50 years later, to derive repeated pleasure from Dylan’s performances of them. These acoustic sets occasionally do drift into a dreamy, slightly zonked vibe that underscores the dense linguistic psychedelia of the lyrics. Also during these sets, Dylan would play long, zigzagging harmonica solos that, at their best, make a decent case for him as a minor virtuoso on the instrument. Other times, though, the solos sound as if Dylan’s stuck in some melodic holes he doesn’t quite know how to get out of. Mostly, he sounds a little bored with the voice-and-guitar format, and eager to turn on the amps, which he’d do during the second half of each concert. This applies to Manchester, London, and every other stop on the European tour. It’s the electric stuff that we need to focus on.

As noted, that 5/27/66 London show was the last show of the tour, and it sounds like an ending in all sorts of mesmerizing ways. In Manchester, Dylan was fierce and defiant, telling lead guitarist Robbie Robertson, bassist Rick Danko, drummer Mickey Jones, organist Garth Hudson, and pianist Richard Manuel to play “Like a Rolling Stone” “fucking loud.” In London, after so many weeks of sparring and scorn, he’s both haunted and ghostly. On “I Don’t Believe You (She Acts Like We Never Have Met)” you can hear the rasping singer have to push himself to get to the notes his songs are demanding. During “Ballad of a Thin Man” Dylan is resigned, as if he’s given up on trying to force any reconsiderations and is instead singing for himself.

It’s entrancing — we so rarely get to hear live recordings of such vulnerability. There’s also an amazing sympathy on display between the beleaguered Dylan’s vocals and the band’s majestic, cresting instrumentation. The Hawks aren’t attacking the music, as they were earlier in the tour, they’re supporting it: Jones and Danko the sympathetic foundation, Manuel providing earthy honky-tonk, and Hudson stitching everything together with his silvery threads. The tempos are slightly slower, too, which lends a little poignancy by underscoring that these musicians were persevering. Earlier in the tour, Robertson’s playing was a riot of spiky, twisted notes. At this show, he’s still aggressive, but there’s grace, too, as on the arcing breaks in “One Too Many Mornings” and spiraling coda of the show-closing “Like a Rolling Stone.” If there was better rock guitar being played in 1966, let me know.

It’s hard to go out night after night and play great music in front of even semi-hostile audiences, listeners who take that music’s existence as an affront, and in London, the impenetrable, enigmatic Bob Dylan was willing to admit it; the between-song banter is devastating:

“Things change all the time,” he says, almost pleading, “you know that.”

“I realize it’s loud music and all that kind of thing … if you’ve got some improvements you could make on it, that’s great.”

“What you’re hearing here now is the sound of the songs. You’re not hearing anything else … so you can take it or leave it. It doesn’t matter to me.”

“I’m sick of having people thinking ‘what does that mean?’ It just means nothing.”

If Manchester was the sound of a fuse burning, London is the explosion’s stark aftermath. When the tour ended, a frayed and frazzled Dylan went back to America. That summer, he crashed his motorcycle while riding near his home in Woodstock, New York. A period of recuperation turned into a longer period of reclusiveness. There’s been speculation in the intervening years that the crash wasn’t actually all that bad, and that Dylan simply used it as an excuse to go away for a while. The London show is proof of how much he’d gone through, and of what he’d been trying so hard to achieve.