On October 20, 1981, six members of an organization called the Black Liberation Army robbed a BrinkÔÇÖs armored truck at the Nanuet Mall, killing a BrinkÔÇÖs guard and then two policemen who tried to block their escape. Driving one of the getaway vehicles was a 31-year-old single mother and former member of the Weather Underground named Judith Clark, who, after a chase, was caught and arrested. At trial, Clark refused representation, behaved belligerently, and expressed no remorse; she was convicted on three counts of felony murder, with a sentence of 75 years to life. She has served less than half of that sentence so far, or more than half, depending on how you look at it; she is now 67.

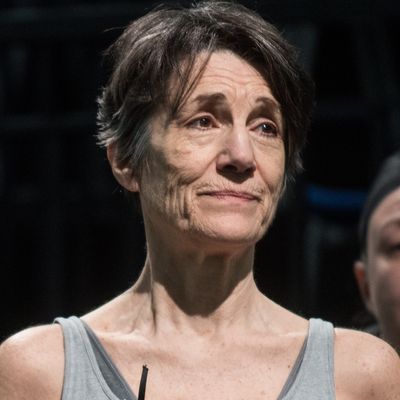

Harriet Walter, who is 66, stars as Clark ÔÇö though she tells us her name is Hannah ÔÇö in the uneven Donmar Warehouse production of The Tempest that opens tonight at St. AnnÔÇÖs in Dumbo. There are several elements of that unlikely sentence that need unpacking. For one thing, there is no Clark, or Hannah, in The Tempest; the central role is, of course, that of Prospero, the deposed King of Naples, living in exile on a remote island with his daughter, his books, his sprites, and his slave. This production is the last in a trilogy of Shakespeare plays that the director Phyllida Lloyd has reimagined as vehicles for an all-female cast and has thus set in a womenÔÇÖs prison. (The two previous installments were a ÔÇ£punk-pugnaciousÔÇØ Julius Caesar, which played St. AnnÔÇÖs in 2013, and a cobbled-together Henry IV in 2015.) The actors in each case play convicts enacting a familiar story, with witty homemade props and costumes, in what appears to be the prison gymnasium. But in those prior installments ÔÇö in which Walter played Brutus and then King Henry ÔÇö the Shakespeare totally dominated; we knew little or nothing of the prisonersÔÇÖ backstories, and the occasional references to cellblock doings seemed intrusive or just silly. Now, in The Tempest, we are finally given to understand that Walter has been playing the same woman all along, and we are told, in a prologue, who she is: the convict Hannah, whose biography is precisely ClarkÔÇÖs.┬á

ItÔÇÖs an ornate frame, but what does it do for the ornate picture it is meant to set off? The Tempest is, after all, a play already overstuffed with magic and poetry and heartbreak and ribaldry. For me, the primary benefit of LloydÔÇÖs concept is the chance to see a great actor in a great role that would normally be off-limits to her. ItÔÇÖs not just that Prospero is a central character; Cleopatra (whom Walter has also played) is a central character, too. But in Shakespeare even a Cleopatra (let alone a Beatrice or a Viola) tends to operate in small circles of domesticity and romance circumscribed by their fathers and husbands, whereas leading men like Prospero engage the whole world. So to watch Prospero, in WalterÔÇÖs muscular performance, give away his daughter to the shipwrecked son of his usurping brother, is to experience a new complexity no male actor could muster, precisely because it is, for a woman, new territory. And Walter, regardless of the gendered qualities she brings to the role, is an uncommonly legible purveyor of human contradiction; opposing feelings are not smeared together in her delivery but are sustained in bright equilibrium.┬á

Though itÔÇÖs a pleasure to enjoy that talent even in miniature ÔÇö check out WalterÔÇÖs perfect turn as Winston ChurchillÔÇÖs wife, Clementine, in The Crown ÔÇö Lloyd has done us a great service in giving Walter a wide range of rangy roles. (We will pass over the awful Taming of the Shrew in Central Park last summer.) I am less convinced that, beyond that casting, Lloyd has generally served the plays themselves. ItÔÇÖs not much of a criticism to say that the rest of the cast is not at WalterÔÇÖs level; who is? But every concept exacts a price, and if your concept is that a bunch of prisoners, with all their diverse accents and perspectives and abilities, is putting on a play, inevitably some of the sophisticated, single-point-of-view beauty of the text is going to be lost. (A good deal is lost, in any case, to cutting; the production runs less than two hours.) Naturally, the bumptious clowning of the scenes involving the drunken castaways is emphasized, faring little better here than it does in traditional presentations. The magic, too, is for the most part limited to what Lloyd can dream up for an ensemble under the threat of lockdown at all times. Finally, when Lloyd really has no choice but to pull out some stops for ProsperoÔÇÖs ÔÇ£We are such stuff as dreams are made onÔÇØ speech, she jettisons the frame altogether, ginning up a complicated sequence involving projections and helium balloons. ItÔÇÖs beautiful, and a bit mystifying ÔÇö and whereÔÇÖs Judy Clark gone now?

Turns out sheÔÇÖs there, albeit mostly obscured by the difficulty of making a play focus on two radically disparate things at once. Still, in the powerful resolution, when Prospero forgives his betrayers and renounces his life of vengeance and spells, the frame story suddenly and movingly reasserts itself. Walter shows us, in an exquisite moment, that this forgiveness ÔÇö of self and of others ÔÇö is no easy business; it may be a resolution but it is also a rupture. Here the idea of rehabilitation, so awkwardly draped over the rest of the plot, finally fits perfectly, and so, briefly, does the specific story of Judy Clark, whose daughter, like ProsperoÔÇÖs, has only ever known her parent in captivity. Partly for that daughterÔÇÖs sake, Clark has said, she has spent her years at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility becoming a model prisoner, accepting her guilt, renouncing her past, and focusing what seemed likely to be a permanent incarceration on helping other inmates.┬á

ThatÔÇÖs a great story, and might make a fine play. (It already made a bad one, in David MametÔÇÖs The Anarchist.) The question is what her tale is doing parked in the middle of ShakespeareÔÇÖs.┬áMost of the time, LloydÔÇÖs production seems to be making an excuse for nontraditional casting instead of merely exulting in it. But on those occasions when it doubles down on themes alive in both stories, particularly the theme of clemency, this Tempest justifies itself. It doesnÔÇÖt hurt that, last month, Governor Andrew Cuomo commuted Judy ClarkÔÇÖs sentence. Like Prospero, she may get to leave her island.

The Tempest is at St. AnnÔÇÖs Warehouse through February 19.┬á