The fact that Iron Fist isn’t a very popular character was, oddly enough, a tremendous opportunity for his screen debut. Although the Marvel Comics character — civilian name Danny Rand — has been kicking around, literally and figuratively, since his 1974 debut, he’s rarely left the publisher’s back bench. His origin story is derivative, his powers are dull, his personality is typically nothing to write home about, and in the modern era, his racial politics are awkward to say the least. Iron Fist does have his fans, but they are a microscopic contingent compared to those who care about the Iron Men and Daredevils of the world.

In other words, few would have mourned Danny if Marvel Television had thrown him overboard for the Netflix series Marvel’s Iron Fist. The powers that be, led by the division’s clever and effective chief, Jeph Loeb, could easily have plucked out the few things that do make the character distinctive, then discarded all the rest. They could have built something vaguely familiar but excitingly new. Of course, this is not the path Marvel Television chose.

Instead, we’re stuck with a show that feels disappointingly rote, despite a few charms. There’s precious little here that we haven’t seen before, and in an entertainment landscape saturated with superhero storytelling, that’s both a crippling flaw and an unforced error. If those who stir superhero brews onscreen want to save the genre from the very real threat of stagnation, the greatest lesson they can draw from Iron Fist is this: Reverence to comic-book source material is often a losing strategy.

Even if you aren’t familiar with Iron Fist’s comics escapades, you’re likely to be all too familiar with what this show serves up. A rich orphan goes to the Far East, gets trained in secret martial arts, becomes his teachers’ greatest champion, and comes back to America to fight evil. Batman, Iron Man, Doctor Strange, Daredevil: All of them have walked similar roads in recent years. Leaving aside the justifiable outcry over the show’s antiquated white-guy-goes-ninja tropes, the biggest problem with Iron Fist is that it’s just dull. There are little bits here and there that make Danny unique: He’s more of a naïf than other famous heroes, his combat powers are centered around a single superhuman punch, and his Asian destination has its own compelling backstory. But other than that, it’s wash, rinse, repeat.

That’s understandable. Loeb and showrunner Scott Buck drew the lion’s share of the show from the adventures that Danny first embarked upon back in the days of the American kung fu craze. (At the time of his first appearance, David Carradine was roundhouse-kicking across the sagebrush in ABC’s Kung Fu every week.) Though co-creator Roy Thomas is one of comics history’s most gifted scribes, the Iron Fist character was not his finest achievement: His most interesting writerly move was to have all the narration done in the second person, e.g., “But you have grown careless, Iron Fist, in allowing yourself even a moment’s contemplation of the carnage your limbs have wrought.” Subsequent writers, including the great Chris Claremont, have always struggled to make him distinctive.

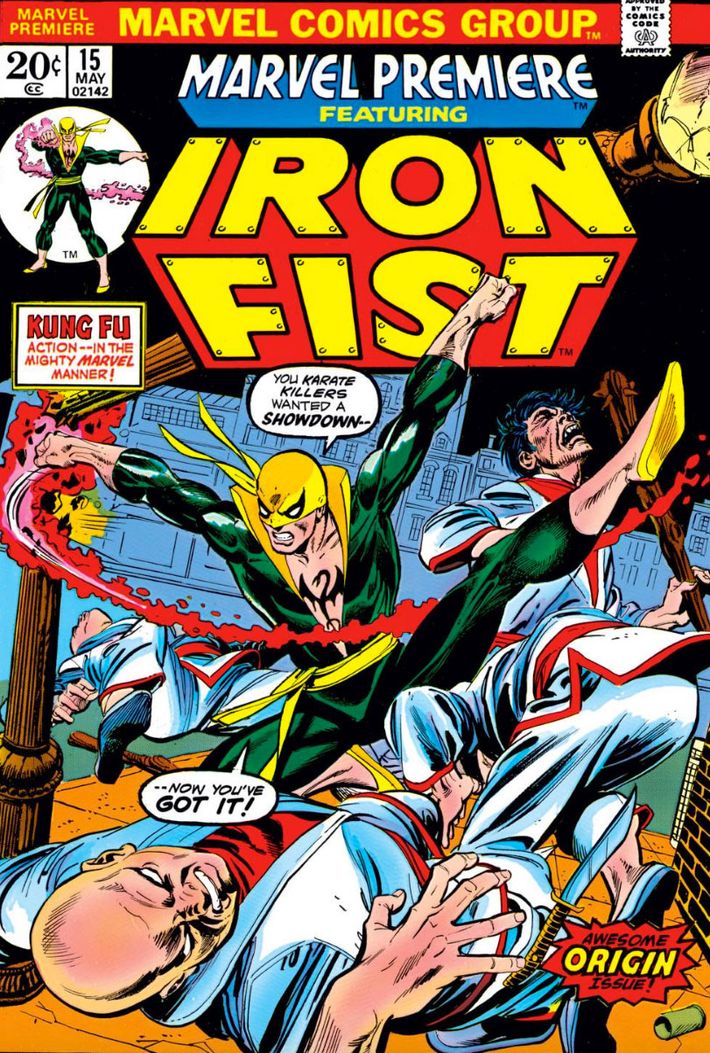

But one thing definitely worked right away: Danny’s costume. Artist and co-creator Gil Kane outdid himself, as did inker Dick Giordano and colorist Glynis Wein, two of the best ever in their respective fields. Iron Fist’s look drew upon elements from martial arts movies — a dragon tattoo, flat slippers, a sash around the waist — while also being distinctively superheroic. His primary color was a deep green, complemented by smiley-face yellow on his absurdly high collar, belt, shoes, and — most important — simple mask, which seemed to consist of a large bandanna with vicious black outlines around the eyeholes. Combine that outfit with coiled poses from Kane and the eventual penciler on Danny’s solo title, John Byrne, and you had visuals that jolted. Iron Fist simply looked cool, which is a key ingredient for the creation of any successful superpowered crime fighter.

It’s hard to determine why a character survives in the Darwinian battle that is American comic-book publishing, but you can make a solid argument that Iron Fist’s look is the primary reason he’s stuck around while other products of the ’70s have vanished. (Woodgod, anyone? Satana? Monark Moonstaker?) There are a few other elements that make Iron Fist exciting: his status as a “living weapon,” the fact that he spent most of his life outside of his home country, and that the site of his training is only occasionally located in this dimension. There’s also the idea, not used often enough, that he’s a bit of a goofball, especially compared to his on-again, off-again partner Luke Cage. He even has a cool ally in the form of fellow martial artist Colleen Wing. Beyond that, though, it’s just hard to care about him.

Of course, that bundle of elements is more than enough to start building a much more interesting Iron Fist. It’s easy to imagine the strategy: Keep the costume, the karate, the power, and the humor, and throw away all the stuff that doesn’t work. Why should Marvel marry itself to a boring origin story that is hardly a beloved one? Why should they stick with a white guy, when — and I say this not out of progressive belief, but an appreciation of good storytelling — other choices would be more interesting? Why should he even be named Danny Rand? Get a bunch of creative writers who love the superhero genre, then let them run wild to reinvent the character.

The fact that such things rarely happen is a serious problem for the superhero economy. When screen adaptations happen, there may be a few changes here and there — e.g., Captain America being the same age as Bucky Barnes during World War II, rather than significantly older — but reverence is generally the order of the day. That’s useful when the origin stories or character tropes are transcendent, as they are with, say, Batman and Spider-Man. But otherwise, you’re tying yourself down. As Logan writer-director James Mangold put it to me recently, “The reality to me is that you can’t have interesting movies if you tell a filmmaker, ‘Get in this bed and dream, but don’t touch the pillows or move the blankets.’” Iron Fist is an immaculately made bed, one that looks just like the way it was before Buck and Loeb showed up. But it wasn’t that pretty a bed to begin with.

Reverence is overrated, and superhero fiction has demonstrated why plenty of times in the past. Hawkeye used to be a colorful goofball with a criminal past until he was reinvented as a leather-clad black-ops veteran in a comics series called The Ultimates, which led to his successful screen incarnation in The Avengers. The aforementioned Bucky was a cheerful kid who was dead as a doornail after a World War II accident, until he was revamped as a troubled adult assassin to great acclaim and success. Batman used to carry guns. Back in the day, Superman wasn’t able to fly. The first dudes to bear the names the Flash and Green Lantern retired and were replaced by completely different people with different personalities and backstories.

Even Iron Fist got a stark shift in tone, scope, and backstory during Ed Brubaker, Matt Fraction, and David Aja’s masterful run with the character in the aughts. It expanded and altered the Iron Fist mythology, positing that he was merely one in a millennia-long line of people to hold that title. As such, we got to see past Iron Fists, all of whom had idiosyncratic character traits and backstories. (The best one was a pirate queen who defended her homeland from white invaders.) It could’ve been very easy for the show to similarly take the basic tenets of that concept and apply it to a totally different person or plot.

Applying such expansive imagination to an existing superhero archetype is not as difficult as it may seem. Take, for example, Mangold’s Logan. Sure, it features everyone’s favorite angry Canadian mutant, but its setting, structure, and thematic goals are wildly different from any other X-Men — or superhero — movie we’ve ever seen. Moving forward, it’d be great to see more mold-breaking ambition like that in the lucrative world of spandex-clad television-making. Beyond a desire to simply see something new, it’s also in the best interests of the genre’s shepherds. After all, the superhero boom’s long-term success is hardly assured — we may very well be in the midst of a bubble that could pop at any moment. In any trend-based glut, the innovators are the ones most likely to survive.

It may have seemed fine to crank out another Marvel Netflix show that feels like the brand’s past outings, but the critical drubbing that Iron Fist has received is in no small part due to the fact that it’s so stale and unoriginal. The reason the Marvel Cinematic Universe succeeded initially was because it offered a bevy of ideas and characters that were somewhat familiar, but also fresh and unlike anything else we’d seen in superhero filmmaking. That mix of comfortingly old and boldly new is necessary for any brand — or, indeed, any genre — to go the distance. The failure of Iron Fist should serve as a cautionary tale: It’s a time to change or die, and whichever studio learns it doesn’t always have to maintain a white-knuckle grip on what’s been done before will be the one that pulls ahead. Reimagination is just as important as imagination in superhero fiction. It’s time to stop fearing it.