Each month, Boris Kachka offers nonfiction and fiction book recommendations. You should read as many of them as possible.

Her Body and Other Parties, by Carmen Maria Machado (Graywolf, October 3)

A striking first story collection mines fresh territory at the intersection of fairy tale horror, metafiction, and feminism.┬áThe bodies of the women in 12 stories bear the marks of misuse as well as the means of escape. A young wife with a ribbon around her neck puts an Atwoodian gloss on an old horror tale; the special victims of Law & Order haunt the televised living; a survivor of sexual assault can hear the thoughts of porn stars. MachadoÔÇÖs women also know their desires and fulfill them, befitting the work of a writer of pseudonymous erotica.

We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy, by Ta-Nehisi Coates (One World, October 3)

CoatesÔÇÖs subtitle is everything. The essayist was so quickly taken up as the voice of his black generation that itÔÇÖs easy to forget how provocative his arguments are, and also how divergent from the hopeful worldview of the president whose eight years formed the rising action of this collection. Coates links his previously published pieces with new interstitial essays tracing an arc that bends away from justice. His skepticism of progress was confirmed with the election of the ÔÇ£first white president,ÔÇØ the subject of his last essay, which is deep, fierce, and to quote its subject, sad.

Manhattan Beach, by Jennifer Egan (Scribner, October 3)

We donÔÇÖt normally come to EganÔÇÖs novels ÔÇöcool and often jagged narratives like her Pulitzer PrizeÔÇôwinning A Visit From the Goon Squad ÔÇö for the classical satisfactions of fiction. This lush, multilayered novel of World War IIÔÇôera New York, about a woman diver in the Navy Yard, her absent father, and the gangster who connects them, is a right turn for an author more comfortable amid post-millennial discomfort. But her mastery of technique and detail make it worth the effort for Egan, her loyal readers, and especially those who love historical fiction despite its generic constraints.

Dunbar, by Edward St. Aubyn (Hogarth, October 3)

Hogarth PressÔÇÖs Shakespeare series, wherein acclaimed writers modernize eternal plays, makes the perfect match between St. Aubyn, master anatomist of solipsistic upper-class decay (via his semiautobiographical Melrose novels), and King Lear. His modern Lear is a media mogul in the Murdoch mold, dispossessed via boardroom coup and dispatched to a nursing home, whence he breaks out with a washed-up comedian (the fool, of course). Throw in a Cordelia reminiscent of Tiffany Trump ÔÇö the late-marriage daughter as virtuous foil ÔÇö and finish with a strong brew of St. AubynÔÇÖs high-grade hallucinogenic wit.

Voices in the Dark, by Ulli Lust, trans. by John Brownjohn and Nika Knight (New York Review Books, October 10)

LustÔÇÖs debut graphic novel has an unusual provenance: an Austrian cartoonistÔÇÖs┬áadaptation of a 1997 novel about sympathetic Nazis, recently translated from German to English. ItÔÇÖs actually a coup for the small NYRBÔÇÖs fledgling comics division. Lust, author of the acclaimed graphic memoir The Last Day of the Rest of Your Life, turns The Karnau Tapes, Marcel BeyerÔÇÖs chronicle of a quirky, Nazi-employed sound engineer who befriends a daughter of Joseph Goebbels, into a completely sui generis work: a masterpiece in faded hues, expressionistic pen strokes, and panels laid out to amplify a painful story.

The Power, by Naomi Alderman (Little, Brown, October 10)

A speculative novel in which women wield all the power ÔÇö after training their fingers to deploy electric shocks ÔÇö can go a number of ways, not all good. Alderman has the daring and good sense to eschew go-girl uplift in favor of terrifying and complex dystopia. What would sexual domination, bullying, religious flimflam, and populist tyranny look like in a matriarchy? Just as bad, but different. Like many sci-fi predecessors, Alderman frames the narrative as buried history in a distant future where the polarities are so thoroughly reversed that a different order is unimaginable.

The GourmandsÔÇÖ Way: Six Americans in Paris and the Birth of a New Gastronomy, by Justin Spring (FSG, October 10)

As French cuisineÔÇÖs once-powerful hold on the aspirational American middle class fades with time, so does our understanding of how and why it conquered us. Employing his own auteur theory, Spring credits the spread of coq au vin, et al. to six homegrown writers who channeled their Francophilia into delectable cookbooks or indelible memoirs. Julia Child looms largest, but Spring makes room for excellent proselytizers like A.J. Liebling and M.F.K Fisher and even Alice B. Toklas, who followed up her avant-garde partner Gertrude SteinÔÇÖs pseudo-autobiography with The Alice B. Toklas Cookbook (including a recipe for Moroccan ÔÇ£Haschich FudgeÔÇØ).

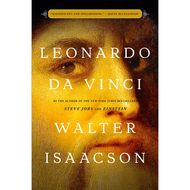

Leonardo da Vinci, by Walter Isaacson (Simon & Schuster, October 17)

The former head of Time and CNN has gone on to a second career of real lasting value, fashioning himself into a biographer of great (mostly) men and really of greatness itself. Though Isaacson has already published praiseworthy tomes on Albert Einstein, Benjamin Franklin, and Steve Jobs, ÔÇ£historyÔÇÖs most creative geniusÔÇØ represents the fresh challenge of understanding the product of an era alien to us. Isaacson does that via prodigious research into da VinciÔÇÖs journals and a sharp if obvious theme: Long before art and science cleaved apart, the self-made inventor-artist sought to know the world with his entire brain.