We forget it now, but when Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers first started recording, it wasn’t clear exactly what genre they represented. (Such things mattered back then.) It’s obvious now that the Heartbreakers are a typical American heartland rock band, though undoubtedly a lot better than most. But at the time, with crazy stuff happening with the Ramones, Elvis Costello, Graham Parker, and punk rock, and then New Wave, Petty & Co. were looped in as some species of this last power-pop division. And that, in turn, was treated with some wariness by the radio gatekeepers of the time.

The group’s first, self-titled album came out in 1976, and it sat around for more than a year with little industry notice. But while no one was looking, its songs were sinking into the country’s collective rock consciousness. It took nearly 18 months for the song “Breakdown” to creep into the American Top 40.

To No. 40, for one week.

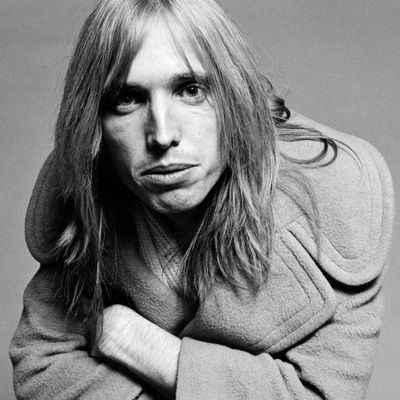

Still, it was clear that Tom Petty — who died today at 66, of cardiac arrest — had done what a real star needs to do: deliver the goods on his first album. “Breakdown” had a primal feel, built on a deceptively lazy guitar line and — apparent on any listen today, but somehow difficult to discern back then — a blistering vocal performance. Petty had also done something else: written an even better and more lasting song in “American Girl.” (More on that in a minute.)

Petty grew up, as his fans know, in Gainesville, Florida — a college town, his Southerness a step removed from the Deep South. His paternal grandfather married a Native American cook and may have had to skedaddle from Georgia and wound up in Florida. Petty has said that most of his relatives are dark-skinned and dark-haired, and he’s the only fair-haired one.

When he was 11, his uncle had a bit part in an Elvis Presley movie being filmed in Ocala. (This was the deservedly forgotten Follow That Dream.) His aunt took him to the set. Petty later recalled that Presley came over and nodded to him. He was an immediate convert, and started singing as a kid, with what turned out to be a lifelong love for rockabilly records; he said that he never wanted to be anything other than a musician.

Petty was a “tender, emotional kid,” as he put it, and bedeviled by a father who had little use for such a son. “He was a hard man, hard to be around,” Petty told journalist Paul Zollo. “He was really hard on me. He wanted me to be a lot more macho than I was.”

Petty knew he wanted to be a music star, but didn’t know how to do it. Seeing the Beatles on Ed Sullivan showed him how. He would have been 13 at the time. He started growing his hair long, and tried to write songs. He found a band to play in. This aggregation, called the Sundowners, learned four songs, which they played, and then played again, at a high-school dance. A local college kid said they could play his frat — if they learned more songs. They played there, and then a Moose lodge, and then Petty was a professional musician, at 14.

As time went on, his hair and dress grew wilder; for Florida, in the early- and mid-1960s, this wasn’t normal. His dad’s displeasure grew to beatings.

By the 1970s, he had a band called Mudcrutch, which actually toured. Mudcrutch had a guy named Tom Leadon, who was the brother of Bernie Leadon, later of the Eagles. (Don Felder, also a future Eagle, was in Gainesville around the same time.) There was also guitarist Mike Campbell, and keyboardist Benmont Tench, who would both move forward with Petty into the Heartbreakers.

By the time the Heartbreakers tried to get a recording contract, Petty was 26 and a ten-year veteran of the business. His influences were Presley, the Beatles, and the Stones, true, but also Dylan, the Byrds (some would say too much so!), Aerosmith, and everything in between.

The band went to L.A. and started calling record companies, literally using a list of names and phone numbers Petty had happened to find in a phone booth. (He grasped that it was a sign that a lot of bands were looking for a label.) They actually found all sorts of interest, came to an agreement with London Records, and went back to Florida to pack up and move to L.A. Then they got a call from Leon Russell’s label, Shelter, in Oklahoma — would they stop by Tulsa on the drive out to L.A.?

They did and met producer Denny Cordell, who had displayed great sonic talent on classic ’60s work by Procol Harum (including “A Whiter Shade of Pale”) and Joe Cocker (including Cocker’s innovative take on “With a Little Help From My Friends”). They canceled their London offer and decided to work with Cordell.

It wasn’t all smooth. The Mudcrutch album was a flop, and the label decided it wanted Petty as a solo artist, without the band. Some chaos resulted, but in the end Petty emerged with the extremely valuable Tench and Campbell and a tough rhythm section of Stan Lynch on drums and Ron Blair on bass, in an aggregation rechristened the Heartbreakers. They put together Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers. The band got some notice in the UK, but America just didn’t seem interested. Finally, a New Wave station in L.A., the mighty KROQ, began to play the album.

The Heartbreakers’ second album was basically done before the first one broke. You’re Gonna Get It had a couple of power pop tunes that got some airplay, but didn’t really go anywhere. Then Petty met up with Jimmy Iovine, who can certainly claim to have given the artist something. Damn the Torpedoes burst out of the radio. The singles were undeniable but also unconventional — “Don’t Do Me Like That” (a song he’d written in the Mudcrutch days) has a weird raggedly guitar line and irregular rhythms but its clever rhymes and jauntiness made it an instant hit. And “Refugee” was a new kind of rock single: Quiet to start, with a sneakily killer lead-up to the even-more-killer chorus, and some silky guitar lines that hearkened back to “Breakdown.” Two other tracks, “Even the Losers” and “Here Comes My Girl” got regular airplay.

Petty’s voice sounded great and varied, too. It’s actually a weak instrument, and can sound strangled and reedy. Recorded well, however, it is a striking part of his best songs. It was clear around here then, too, that the Heartbreakers were a formidable band — Tench was a full-bodied musician, and Campbell a fluid and articulate soloist — and the cowriter of some of Petty’s best songs. Torpedoes went multiplatinum, and Tom Petty was a star. (And Petty’s dad suddenly became a fan.)

Interestingly, Petty didn’t adequately capitalize on Torpedoes. His succeeding albums had good songs, but none were commercial juggernauts. To his credit, he fought with his label when necessary. Leon Russell’s Shelter Records was bought out by MCA (now Universal); Petty quickly learned how vulnerable the contracts he’d naively signed made him. Torpedoes was delayed for months while he fought with the label. That battle Petty basically won. But it reared its head again a year later. This was the age when the labels magically all decided to raise their prices at the same time, generally by using superstar product to get fans used to it. Petty threatened to rename his fourth album Hard Promises as $8.98, which would have contrasted starkly with MCA’s proposed record-setting retail price of $9.98. He won.

He trundled through the 1980s, and eventually found himself by far the youngest member of the Traveling Wilburys, the weird geezer supergroup that included George Harrison, Bob Dylan, Jeff Lynne, and Roy Orbison.

With Lynne, the Electric Light Orchestra founder turned superproducer, he crafted a solo album without the Heartbreakers. (Petty and Lynne wrote most of the songs.) It was called Full Moon Fever and included the song “Free Fallin’.”

This is a great song. As I read it, it’s a devastatingly simple construction. There’s a guy who’s broken his girlfriend’s heart. He says, “I’m free,” and then immediately realizes what “free” is going to mean: “free fallin’.” The song’s evocations of the San Fernando Valley give it an immediacy like few others of the era. And while Lynne’s production overall is, I think, far too sterile and far too reliant on sound effects, who’s going to argue with that six-note guitar line?

The album also contained the big radio hits “Runnin’ Down a Dream” and “I Won’t Back Down.” A decade on from Torpedoes, with 5 million copies sold in the U.S. alone, this put Petty back into superstar realm.

In the years since, he was a rock elder, released this and that album that few paid attention to, and eased himself into the comfortable superduperstar stadium tour circuit, where nightly paydays reached into the millions. He let Peter Bogdanovich do a four(!)-hour documentary on his life and the band called Runnin’ Down a Dream.

While Petty’s image was laid-back, almost hippielike, you don’t get to be a star and stay one without some grit. His kids, he told Zollo, know the truth: “They said, ‘The world pictures you as this laid-back laconic person, but you’re really the most intense, neurotic person we’ve ever met!’”

Some of Petty’s stuff doesn’t work for me. He was cranky about women in too many songs. I don’t get Southern Accents. Too much of the ’80s MTV stuff is fluff. But there will always be one song: “American Girl.” And not only that, there will always be one line in that one song: “Raised on promises.” The context is this:

She was an American girl

Raised on promises.

In that line resides the promise of America, and rock and roll, and the intercontinental railway, the interstate highway system, and Microsoft and Apple and Google and even Facebook. As I said, later Petty would sound pinched writing about women, and maybe he didn’t understand what he was writing about them. But an American girl, raised on promises, is everything this country is about.

The story as it unfolds isn’t entirely clear, but I read it like this: She had a guy, and he was either not enough, or, in the end, she realized it was going to be a relationship that was going to hold her back. So she left, she stood on a hotel balcony, and looked at a freeway.

Maybe the song is about something else, but that interpretation exists in it, and that’s what it’s about for me. We could argue about it, but I’d win, because on my side I’d have the guitars that come in after those last lines, the steady one-chord jangle, the uplifting bass line, Tench’s swelling organ, then Campbell’s deceptively emotional guitar solo — all of that, until a flurry of guitar, faster and faster, onward and upward, takes our girl to where she needed to go.

The band played its last show Monday, concluding a three-show stand at the Hollywood Bowl — the last shows of the Heartbreakers’ 40th anniversary tour.