A week after my mom died, I tried to return a shirt I had bought her for Christmas that she had refused to accept. (My mother was an incredibly generous giver of gifts, but could not stand receiving them.)

I went to Lord & Taylor with the shirt and my receipt, but the woman at the register said too much time had passed to fully refund my money. I accepted the partial reimbursement, feeling a little annoyed. At that very moment, I heard Tom Petty on the store’s P.A. system. “Don’t do me like that,” he sang, vocalizing my thoughts. “Don’t do me like that.” Suddenly, my mother was right there next to me, cracking up, and poking me in the ribs to make sure I got the joke.

My mom loved a lot of the music that I loved. She genuinely enjoyed Duran Duran and not just to seem like a cool mom à la Amy Poehler in Mean Girls. She was a fan of Stevie Nicks, R.E.M., the Police, and INXS. When I was in tenth grade, for several days, I was unable to locate my copy of Appetite for Destruction. I eventually figured out that my mom had borrowed it so she could listen to it on the cassette player in her car.

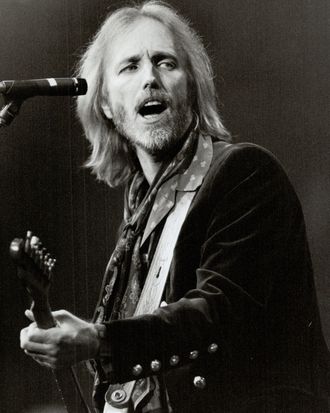

But there was no musician that woman loved more than Tom Petty. When the news broke that Petty died suddenly, at age 66, it was like losing my mother all over again. Because my own childhood ran on a parallel line with the rise and apex of Petty’s career — I was seven when Damn the Torpedoes was released, and 17 when “Free Fallin’” was so popular you couldn’t cross the street without hearing “and America, too” — Petty’s loss feels personal. And because my mother made sure I grew up hearing that twangy, dusty American road of a voice in our house constantly, it’s also crushing.

Much will be written about how Petty’s songs were so quintessentially American, and how he was able to speak to residents of states red as well as blue. Petty was mostly apolitical as a performer, but seemed to lean left — he was certainly pleased when Barack Obama and the Democratic National Committee used “I Won’t Back Down” — and yet he could easily make you think he was just a good ol’ boy. He sang about how “there’s a Southern accent, where I come from,” and stuck his thumb in the eye of corporate greed and the Establishment. He could rock the hell out, but always seemed as chill as the Dude after a couple of White Russians. Tom Petty was a like a compact disc — if you held him in the light and looked at him, you could see a whole bunch of different, recognizable colors being reflected.

I am sure much will also, rightly, be said about how great his music videos were (“Don’t Come Around Here No More” is a more definitive Alice in Wonderland than the movie Tim Burton made), and what an amazing live performer he was, and how effectively his music was used in TV and film. (It goes without saying that the use of “Free Fallin’” in Jerry Maguire was fantastic, but as one of the few defenders of Cameron Crowe’s We Bought a Zoo, I’d like to add that “Don’t Come Around Here No More” is deployed in that film just perfectly.)

Ultimately, there are two simple reasons why Petty’s death is so devastating for so many people, myself included: because his career was so long, it felt like the sound of him was always around, and because his songs were written with such specificity, they felt extraordinarily personal. Those two things make going through his discography less a revisitation of the albums and songs he released, and more like flipping through an old photo album.

I hear “Refugee,” and I see my mother, rocking back and forth in our living room recliner like Grandma Saracen on Friday Night Lights, while watching one of her VHS tapes of a Petty concert. She is singing “Refugee,” and she is not giving one single damn that she sounds terrible.

I hear “Here Comes My Girl” and I see myself as a kid trying to float in our tiny, makeshift backyard swimming pool while looking up at the sky, and mouthing the words, “I can tell the whole wide world, shove it, hey!”

I hear “Running Down a Dream” and I see Tom Petty onstage at my college sounding exactly like he did on the record, but somehow even better.

I can hear even a single note of any of those songs and many others and immediately remember the memorial for my mother, where I played practically nothing but Tom Petty because hearing him was so wrapped up in my memory of her. I know this experience is similar to how others are feeling because I have seen so many people on Twitter and Facebook posting snatches of lyrics from his songs. They didn’t even need to identify which tracks they meant, because we all know them. They are in our blood.

You can say Tom Petty’s music represented perseverance, a sensibility that felt uniquely American, or the spirit of a summertime that would never end. Those things are true. But when you consider when he died — a week after the last date of what he said would be his final tour with the Heartbreakers, and on a day when the nation was mourning so much loss that occurred at a concert — it’s impossible not to consider the connection between his music and life itself.

Tom Petty’s music sounded like what it felt like to be alive.