Charles Manson, the man who convinced his followers to commit a notoriously brutal spree of murders in 1969, has died. But as far as pop culture is concerned, Charles Manson is alive and well.

In the half-century since Manson’s acolytes killed pregnant actress Sharon Tate and four others on an August night in the Hollywood Hills, then murdered grocer Leno LaBianca and his wife, Rosemary, the evening after, the remorseless cult leader and his crimes have inspired all manner of popular art and artists. That includes books (Helter Skelter, last year’s The Girls by Emma Cline); plays (an opera called The Manson Family and Stephen Sondheim’s Assassins, in which Manson follower Squeaky Fromme plays a key role); films (the 1973 documentary Manson and the more recent indie comedy Manson Family Vacation); music (Marilyn Manson is named, in part, after him, while the Sonic Youth track “Death Valley ‘69” is about the Manson family); and television shows (the NBC series Aquarius, not to mention a lot of allusions in Mad Men).

This year in particular, Manson has become even more prominent as an onscreen subject. He loomed large in American Horror Story: Cult, appearing as a character played by Evan Peters, who inspired the mind-set of the present-day, increasingly unhinged cult leader Kai Anderson, also played by Peters. The episode “Charles (Manson) in Charge,” which aired just two weeks ago, features a lengthy reenactment of the night when Tate, Jay Sebring, coffee heiress Abigail Folger, Voytek Frykowski, and Steven Parent were shot, stabbed, and beaten to death by Manson’s followers. In that episode and last week’s finale, Kai — a misogynist inspired by Donald Trump’s victory to “start a movement” — has frequent visions of Manson, whom the mentally disturbed Kai sees as a sort of spiritual guide.

The second season of Search Party, which focuses on a quartet of Brooklyn millennials attempting to cover up their roles in committing murder, also directly acknowledges Manson. Portia (Meredith Hagner), the self-involved actress in the group, stars in a Manson-inspired play called LaBianca that’s staged during an upcoming episode. In it, Portia plays one of the many female followers persuaded to do the bearded wacko’s homicidal bidding, a sly commentary on Portia’s own tendency to follow the orders issued to her by others, including her guilty friends and the Svengali-ish director of LaBianca, played by Jay Duplass.

In the Netflix series Mindhunter, which focuses on a pair of FBI agents in the 1970s who interview serial killers as part of their research on psychological profiling, Manson is mentioned as the holy grail of convicted-killer interview subjects. He never appears in season one, though apparently that’s a possibility for the show’s second season.

We’re likely to see more of the late convicted murderer on the big screen courtesy of Quentin Tarantino’s planned movie about Manson, and a possible adaptation of that aforementioned Emma Cline novel The Girls. Other cult leaders, like David Koresh, who also was referenced in American Horror Story: Cult, will be getting renewed attention, too: In January, the Paramount Network will air Waco, a series about the showdown at Koresh’s Texas compound, with Taylor Kitsch in the lead role.

All of these projects were obviously in the works or completed well before Manson died. But more than anything else, this recent trend to depict Manson and his so-called family is evidence that their horrible acts have never stopped creeping their way into popular culture and probably never will. As American Horror Story: Cult conveyed with occasional success, Charles Manson’s crimes also feel more timely than usual.

Manson was an alienated white boy who grew into a disenchanted white man with famously racist views — Helter Skelter, a name inspired by the Beatles song, described his vision of an apocalyptic race war — and a swastika emblazoned on his forehead. In other words, if he weren’t in jail, he might have fit in pretty well with the alt-righters who marched earlier this year in Charlottesville.

He also had a disturbing ability to groom other people — young women especially — and get them to do his work for him. People often forget that while Manson came up with the plans for those summer of ’69 murders, he never did any of the shooting or stabbing himself. He abused his power, convinced his followers to get their hands dirty, and never appeared to feel an ounce of guilt about any of it. As the New York Times obituary noted, when Charlie Rose once asked Manson if he cared that he had ended the lives of Tate and her unborn child, he responded, “What the hell does that mean, ‘care’?” He was the quintessential unrepentant angry white man, a figure that has a prominent cultural place in forms both fictional and, sadly, nonfictional.

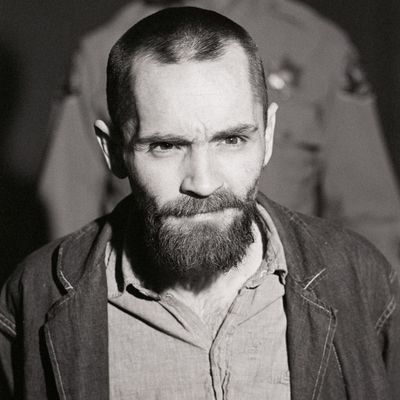

Perhaps Charles Manson also remains a source of such horror and continued fascination because he was the ultimate symbol of insanity. With eyes that either projected total blankness or the agitated evil of a demon awakened, Manson looked like what most people stereotypically think of when they imagine a crazy person. In what may be the craziest time that many Americans have lived through, it makes twisted sense, then, that the most recognizable American psycho is still so omnipresent in our culture.

Charles Manson is dead. But Charles Manson is also, for better or worse, going to live forever.