To review DC ComicsÔÇÖ Doomsday Clock is to row into the choppy waters where art meets commerce. Do you merely assess the work, or must you also pass judgment on whether the work should exist in the first place? After all, there are those who consider it an abomination. ItÔÇÖs a sequel to Watchmen, the mid-ÔÇÖ80s graphic novel often regarded as the greatest superhero story ever told, but that workÔÇÖs creators ÔÇö writer Alan Moore and artists Dave Gibbons and John Higgins┬áÔÇö had nothing to do with it. It takes that workÔÇÖs bitterly cynical characters and introduces them to the Day-Glo cohort of the mainstream DC superhero universe. Moore openly detests DC, but the publisher owns the underlying intellectual property, so whatever his wishes might be, theyÔÇÖre moot. You can argue that Doomsday Clock is a step back for creatorsÔÇÖ rights, and you wouldnÔÇÖt be wrong. Even I had serious doubts about it, way back when it was still being gestated.

So if you were to ask me to review the process that put the first issue of Doomsday Clock on stands today, IÔÇÖd tell you that I donÔÇÖt exactly approve of it, though my disapproval isnÔÇÖt vehement. No laws were broken and no one is bankrupting Moore or his collaborators. (If you want a persuasive and detailed argument against the comic on ethical grounds, check out Chase MagnettÔÇÖs essay over at Comics Bulletin.) If you can look past the circumstances of its birth, youÔÇÖll find this opening chapter to be one of the better single issues of a superhero comic published this year.

The pedigree behind the work is high. It comes from the drawing board of penciler Gary Frank; the paintbox of colorist Brad Anderson; and the word processor of DCÔÇÖs president, chief creative officer, co-head of movie operations, and all-around golden boy, Geoff Johns. That team was responsible for the delightful graphic novel Batman: Earth One, a stand-alone Batman tale that displayed FrankÔÇÖs expert textures and facial acting and AndersonÔÇÖs knack for mood-setting. But most important, it represented a leap forward for Johns. In Earth One, the acclaimed superhero scribe demonstrated a facility for setting a tone of anxious dread, drawing out his pace, and twisting existing characters in ways that didnÔÇÖt feel like cheap gimmicks. It was, in my opinion, his best work to date, but he might be on track to outdo it with Doomsday Clock. Maybe.

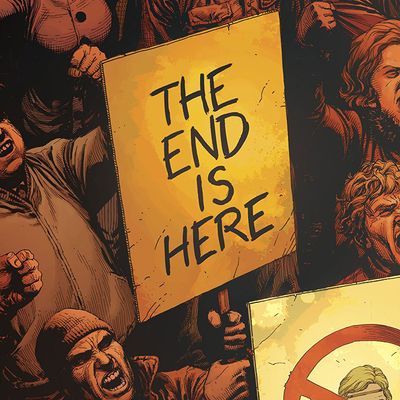

Here, we open in media res ÔÇö but perhaps ÔÇ£openÔÇØ isnÔÇÖt the right word, as the story begins before you even get to the first page. The cover ÔÇö an angry mob bathed in the orange light of flame, a placard reading ÔÇ£THE END IS HEREÔÇØ stationed at the center ÔÇö is the first panel of the story. This was a technique that Moore and Gibbons employed for Watchmen, and Doomsday Clock is nothing if not faithful to the technical idiosyncrasies of the work that preceded it. Narration comes not in the form of a third-person omniscience but rather the grim ramblings of the fatally principled vigilante Rorschach (who may not be what he seems), panels often mirror one another compositionally and thematically, thereÔÇÖs post-narrative back matter in the form of documents from within the storyÔÇÖs universe, and the chapter is both titled and concluded with an excerpt from a work of literature.

The choice of that quotation is a nice demonstration of JohnsÔÇÖs clever efforts to both honor and expand upon Moore. Rather than opting for a hoary verse from scripture or a line from an eye-rollingly well-known novel, the writer plucks from the poem ÔÇ£OzymandiasÔÇØ ÔÇö but not the one by Shelley, which was so prominently employed in Watchmen. No, he goes with the more obscure companion poem of the same name, written by Horace Smith and published just a few weeks after ShelleyÔÇÖs in 1818. It works as an homage, but the lines apply well to the tale heÔÇÖs trying to tell, all portent and pessimism.

That tale is both a thrill and a logical extension of the situation at the end of Watchmen. ItÔÇÖs 1992, a little over half a decade past the day the worldÔÇÖs smartest man, Adrian Veidt, executed a hoax alien invasion that killed millions in the name of ending the Cold War and averting nuclear disaster. The original story concludes with the ethical quandary of whether or not that step was justified, but makes it clear that, at the very least, it accomplished its aims of bringing about global stability. In Doomsday Clock, we learn that the peace was fragile, and that it outright crumbled when the hoax was revealed for what it was. The nascent European Union has collapsed. Russia is threatening to march on Belarus. The American vice-president has, for reasons unexplained, murdered the attorney general. Martial law is imposed. ItÔÇÖs all a smidge over the top, but if youÔÇÖre going to revisit the pre-apocalyptic tone of Watchmen, you might as well pump the gas a little.

Plus, the geopolitical Grand Guignol is tempered significantly by the tight, naturalistic approach to the core story, in which Rorschach (or a Rorschach) recruits some previously unseen allies for a mysterious crusade. Johns has found a muse in the form of MooreÔÇÖs beloved and philosophical killer, providing terse verbiage that titillates in the way it harks back to his original incarnation (e.g., ÔÇ£God turned his back, left Paradise to us. Like handing a five-year-old a straight razor. We slit open the worldÔÇÖs belly. Secrets came spilling out. An intestine full of truth and shit strangled usÔÇØ). The new additions are welcome, too: one is, believe it or not, a killer mime, and FrankÔÇÖs rendition of a balletic beat-ÔÇÖem-up pairs well with JohnsÔÇÖs rendition of what, exactly, a killer mime would do to get what he wants.

It all serves to butter us up for the most controversial part of the narrative, the one that has everyone nervous about how Doomsday Clock will play out: the arrival of the mainstream DC superheroes. One of WatchmenÔÇÖs great virtues was its independent status ÔÇö it was a self-contained story that was wholly removed from the world of Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and their spandex-clad ilk. That was the only way it could convey one of its central points, which was that superherodom is a fundamentally perverse endeavor, and that a real-life superhero would be unlikely to have any actual superpowers. The tout of Doomsday Clock is that itÔÇÖll allow the DC and Watchmen universes to encounter one another, which is quite the dicey gambit.

Along those lines, this first issue may well be the last to focus primarily on extending the Watchmen narrative. The tightly gripped secrets of this much-hyped series could reveal themselves as the crude, fleeting delights of a mash-up. As such, the real test will come with issue number two next month. The clock is ticking.