Each month, Boris Kachka offers nonfiction and fiction book recommendations. You should read as many of them as possible.

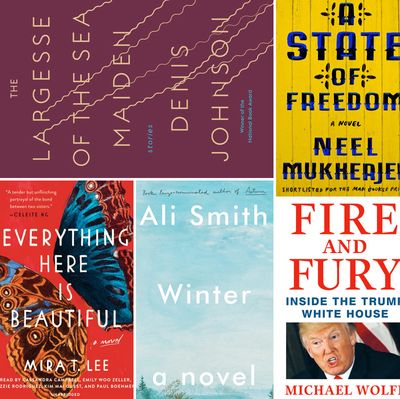

´╗┐A State of Freedom, by Neel Mukherjee (Norton, January 1)

The Indian-born Londoner MukherjeeÔÇÖs first two novels, including his Booker-short-listed The Lives of Others, focus tightly on people crossing boundaries of class and country. This one is more episodic and ambitious: five linked short novellas branching out from a devastating opening vignette ÔÇö about an Anglo-Indian touring Agra with his 6-year-old son ÔÇö into lives determined and divided by castes, communities, and generations. Through the eyes of a servant from a dirt-poor village, an ill-fated construction worker, or a man and his much-abused bear, hope wrestles with despair, and death has the last word.

Fire and Fury: Inside the Trump White House, by Michael Wolff (Henry Holt, January 9)

Did you enjoy your holiday break from the furious black hole engulfing our government? Instead of reading tweets, settle in with the new yearÔÇÖs best thriller, wherein a deeply unqualified man becomes president and then threatens to destroy the world by dint of his monstrous ignorance and narcissism. Wolff spent many months cultivating Trumpites and stole away with the goods in broad daylight. Our only hope is that at least a few of his scariest anecdotes about TrumpÔÇÖs bumbles, BannonÔÇÖs manipulations, and everyone elseÔÇÖs abject groveling are not completely accurate.

Winter, by Ali Smith (Pantheon, January 9)

The second in SmithÔÇÖs quartet of seasonal novels displays her mastery at weaving allusive magic into the tragicomedies of British people and politics. Once-commanding Sophia, perhaps going mad on a Cornwall estate, is haunted both by history (her dead celebrity husband; Brexit) and an ever-morphing vision of a childÔÇÖs floating head. Her sister is an activist in Greece, her son a London nature writer who pays a stranger to stand in for his girlfriend at Christmas. Their holiday get-together generates a bleak, beautiful tale greater than the sum of its references (A Christmas Carol chief among them).

Grist Mill Road, by Christopher J. Yates (Picador, January 9)

YatesÔÇÖs first novel, Black Chalk, was the Secret HistoryÔÇôish chronicle of a cruel game among Oxford freshman. Here too he tracks the lifelong consequences of youthful sins, but this time with a longer lens. Patrick and Hannah have a seemingly solid marriage paving over a secret: He witnessed a savage, near-fatal attack on the young teen Hannah by his friend Matthew. (Never has so much pain and suspense sprung from a BB-gun attack.) When Patrick sees Matthew again years later, life begins to unravel once more.

The Largesse of the Sea Maiden, by Denis Johnson (Random House, January 16)

Johnson didnÔÇÖt write enough short stories, even after getting more attention for his casually stunning 1992 collection JesusÔÇÖ Son than for his many novels, poems, and plays. He died last May, at 67, before the publication of this second batch. The two collections compliment each other ÔÇö the first concerned with wasted youth and the (richer, wearier) second with the realization that the end is closer than the beginning. The inventively fragmented title story drives home that wistful theme. But Johnson himself didnÔÇÖt burn out or fade away; he died in his prime.

Everything Here Is Beautiful, by Mira T. Lee (Viking, January 16)

Art has done almost as much as medicine to help us understand mental illness, deploying empathy to cut through the fog of confusing, quicksilver changes that defy neat categories. Like Adam HaslettÔÇÖs Imagine Me Gone, LeeÔÇÖs debut looks at a sufferer ÔÇö in this case Manhattan journalist Lucia, diagnosed with ÔÇ£schizoaffective disorderÔÇØ ÔÇö through her own eyes as well as those of narrators closest to her, including older sister Miranda and Ecuadorian-born partner Manuel. And for extra credit, Lee evocatively depicts the ÔÇÖ90s gentrification of the Lower East Side.

The Wizard and the Prophet: Two Remarkable Scientists and Their Dueling Visions to Shape TomorrowÔÇÖs World, by Charles C. Mann (Knopf, January 23)

The author of rigorous popular histories like 1491 lays out the lives and theories of two incredibly influential thinkers who had opposing answers to the question that dogs us long after their deaths: How we survive our own ravaging of the Earth. The debate is between ÔÇ£ProphetÔÇØ William Vogt, who evangelized for conservation, and ÔÇ£WizardÔÇØ Norman Borlaug, a proto-Silicon Valley utopian who promoted technological cures, especially GMOs. Nobly declining to take a side, Mann offers ringside seats to a historical fight with the highest stakes in the world.

The Monk of Mokha, by Dave Eggers (Knopf, January 30)

As with his nonfiction book Zeitoun, but with lighter and brighter results, the versatile Eggers finds a universe in the life of one man. He follows the Yemeni-American Mokhtar Alkhanshali through the unlikely execution of a quixotic mission: to revive the 500-year-old tradition of Yemenite coffee. Alkhanshali finds himself in mortal danger as Yemen veers toward civil war, but escapes along with a strain of beans that becomes Blue BottleÔÇÖs most expensive cup of joe. Eggers expounds organically and winsomely on global politics, the gentrification of coffee, and the improbable resilience of the American Dream.

If you buy something through our links, Vulture may earn an affiliate commission.